|

Back to |

| The Front Page |

| Archives |

|

Modern croquet takes shape with the Willis Setting by Allen Parker (Parkstone) reprinted by permission from the CROQUET GAZETTE Posted December 10, 1998 |

Precursors to the Internet's Nottingham and Wyoming boards were lively debates in the columns of England's CROQUET GAZETTE and FIELD magazine around the turn of the century, when skill levels of some of the top players were advancing to such a degree that some observers worried about the survival of the sport. Looking back from a century later, we recognize many of the positions so passionately proposed, held, debated, and defended, as exactly the same potential "remedies" discussed today. Observant readers will figure out that in the time of these letters, the game in England and throughout the world started much as it starts in America today - in front of the first hoop; one writer cited below declares "absurd" an opening which allows a point to be scored so easily. It was changed. But other proposals call for the "delicacy of touch" and "refinement of play" seen only in present-day America: losing the turn when one clears a hoop and crosses the boundary line in the same stroke; ending the turn on a roquet out of bounds. These "remedies" for making the International Rules game more difficult and interactive are still being proposed today, but have yet to be seriously considered. We are indebted to the CROQUET GAZETTE and writer Allan Parker (who still plays croquet at Parkstone) for allowing us to revisit his article and reexamine the forces which shaped the present day sport.A wide variety of arrangements of hoops and pegs was in vogue in the early days of croquet, of which two examples were given in a previous article ("Looking Backwards in 1896" in the January 1988 issue of the CROQUET GAZETTE.) The All England Croquet Club setting for the Wimbledon Championship in 1870 is shown in FIGURE 1.

|

|

| Fig. 1: The All-England Croquet Club Setting for the Wimbledon Championship, 1870 | Fig 2: The Hale Setting. TP: Turning Peg. WP: Winning Peg. |

A new setting was introduced by J.H.Hale in 1872, and this was generally adopted and in use for the next fifty years. It differs from our present day setting in having two pegs; a turning peg at the North end of the court, and the winning peg at the South end. It had six hoops, but the middle two were separated by only 7 yards instead of 14. See FIGURE 2.

Although our present setting, the Willis Setting, was not generally

adopted until 1922, it was first mooted in the year 1904, and the events

leading to its testing are illustrated by the following excerpts from

the GAZETTE of that year.

Although our present setting, the Willis Setting, was not generally

adopted until 1922, it was first mooted in the year 1904, and the events

leading to its testing are illustrated by the following excerpts from

the GAZETTE of that year.

The following letter, published in the 1904 GAZETTE, from an old-time player well known in the 'seventies, was taken from the previous week's "Field." As the then editor comments, "It is interesting as showing that the desire for radical changes in the game is not confined to some of the modern players."

The letter was headed ‘Modern Croquet' and continued, "...A process of development and evolution is constantly going on in games, as in other things. There come times in the history of most games when the increased skill of the players renders necessary changes in the laws that govern the play if the game is to hold its own in competition with other games. Such a time is thought by many to have come in the history of cricket, in view of the huge scores and many drawn matches that occur. Such a time came in the history of billiards when the spot stroke enabled one player to monopolise the table and made watching the play a weariness to the flesh, until the stroke was barred. Such a time seems to have come in the development of the modern game of croquet, which living players can remember from its beginning. From the first the game has gradually been made more difficult. Hoops have been narrowed, settings improved, and the laws increased and amended.

"Step by step the game has progressed. As skill overcame difficulties, fresh restrictions have had to be devised, but still the best players have risen superior to the changes, and are practically masters of the game. This mastery, to the prophetic eye, is a danger to croquet. When a game consisting of 28 points is frequently won, with two first class players engaged, by 26 points, the other two points made by the loser being merely nominal ones, it surely does not need much argument to show that there is need of a change.

"A game where practically one player only may occupy the ground from start to finish has reached the stage, which billiards reached with the spot stroke, when some alteration is imperative. The question is...what? Hoops can hardly be made narrower, and though some improvement may be effected in the setting, as I shall try to show presently, no changes in these respects can so materially increase the difficulties of the game as to shorten appreciably the length of the breaks. Where, then, is the remedy to be found?

"Looking back, as I do, upon all the changes and developments of the game with a personal experience of them, one law seems to stand out from all the rest as that which has had most to do with the making of croquet. That law is the one that created the "dead boundary": I recall the game before that law was adopted, and the wonderful change its adoption at once produced in scientific play. I remember, too, the storm of opposition with which it was met, and I am glad to think that I strongly advocated it in the columns of the "Field" with the late Mr. Walsh and 'Cavendish' on the reforming side, some 34 years ago.

Extending the "dead boundary" principle

And now I look again to the extension of the same principle to add fresh interest, science and skill to croquet. I suggest a law therefore that shall make all balls 'dead' not being 'dead' already, as soon as they pass the boundary. In other words, if a ball after running a hoop crossed the boundary, the player would have no further stroke, or if the player's ball struck another ball over the boundary, the same penalty would follow. But if the player's ball, after glancing off another ball, passed the boundary, or caused another ball to pass it, no penalty would follow, his ball being 'dead' at the time.

"The penalty for passing the boundary after running a hoop would not often be incurred, but the danger of striking another ball off the ground would be a constant one. It would, therefore, compel a much greater attention being given to the niceties of strength than has hitherto been the case. So great, indeed, would be the difficulty of hitting a ball on the boundary when shooting from a long distance without knocking it off that I recommend that the bringing in of balls from the boundary should be two yards, instead of one as now.

"This extension of the dead boundary principle will be found, I think, by all who try it to add immensely to the interest of the game, to shorten breaks, to divide the game more equally between the players, and to make games more even. Great skill will have to be developed in the matter of strength, and judgment of pace and delicacy of stroke will become more prominent features of croquet. "Rushing" (a word for which I would substitute "driving" would become still more the fine art which it deserves to be. Its further development alone would, I believe, justify the change that is here proposed. [CWOM editor's note: In 19th Century America, "driving" was a widely accepted term for what we today call "rushing."]

An absurd opening stroke

"As regards the arrangement of the hoops and pegs, there seem to be one or two points in which some alteration would be a distinct improvement. In the first place, it is most absurd that the opening stroke should be so easy that a point is necessarily scored. The reason why it was made so was that originally no ball was in play until it had been through the first hoop. Now that that reason no longer exists, there is no object in making the first point a certainty. The custom remains now as an unmeaning survival from a ruder day, like the appendix in the human frame, though, happily, it can be more easily removed.

"I suggest the following setting of five hoops. Instead of the two middle hoops, one in the centre of the ground, this centre hoop to be run first, the spot from which the first stroke is made being anywhere within one foot of the peg. After the centre hoop has been run, the second hoop to be the one which is now the first, and then the rest of the outside hoops in the present order. After the five hoops have been run once they would be run again in reverse direction.

Why have two pegs?

"The turning peg is quite unnecessary and should be left out, for there is no reason why this point, so much easier to make than the hoops, should be kept in the middle of the game. It merely makes breaks easier, affording a rallying place, which is by no means required. The game would thus be reduced to 24 points, which is quite enough, and those points would be made rather more difficult, which is a desideratum. The final points would be made less easy than now, because the approach to the peg would be from the corner hoop; and, with only five hoops and one peg on the ground, there would be some reduction in the opportunities for wiring, which would be of advantage to the back player.

"As I am no longer playing the game myself, I write from a position of detachment; but as a cool, impartial outsider, my view of the game may be more valuable than that of one more influenced by more personal interests, and therefore blinder to the imperfections of the game that he is playing. The chief objection to making croquet more difficult is that it is hard upon the indifferent performer; but you cannot by such an argument stop the natural development of games. It is skill that must be considered, and it is skill that must be rewarded; but skill must neither be allowed to make a game monotonous, nor enable one player to monopolise the play."

This [letter] was promptly followed by a criticism in the 'Notes' in the following issue: "The letter from the "Field" on "Modern Croquet", which we quoted last week, seems to us to carry with it its own condemnation. The writer's avowed object is to make the game harder for the in-player, and easier for his opponent. With this object in view, he proceeds to suggest an alteration which practically destroys the opponent's one method of getting in - the long shot. Then, observing his dilemma, he proposes another modification - a 'two yards from the boundary' rule which is just the one thing that the in-player requires to make his life entirely happy. With this modification the 4-ball break from any position would become almost a certainty; at any rate all attempts at defensive play would become utterly futile. Mr. Willis' letter in the present number may, perhaps, stimulate the efforts of those who consider that croquet is not yet perfect.....

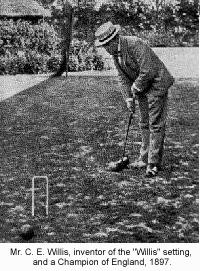

The letter referred to gives a diagram of the Willis Setting. This was exactly the same as the present day setting except that the starting point was a couple of yards in front of the first hoop. There was an experiment with this setting at Roehampton in 1902, but it was not generally introduced until 1922. Some abstracts from Willis' letter are as follows:

"Sir, I have read with great interest the two letters on 'Modern Croquet' which appeared in the 'Field' of June 11th, and as the subject is worthy of discussion, I venture to make a few remarks. Had not Croquet be better left alone, at all events for the present? If it is deemed necessary to make any alteration, this should be slight, and at the same time one that would make the game easier for indifferent players and more difficult for good ones.

"There is no doubt that Mr. Croft is quite right when he says, "There is a certain lack of true sport in Croquet as now played," but I do not think that either of his suggestions is likely to improve matters....

"I am afraid that I cannot agree with Mr. Croft's suggestion that a lawn should be undulating. This would lengthen the game and might cause frightful exhibitions of temper; no one but a saint could remain calm and smiling, if every time he approached a hoop, he found it impossible to run it owing to hills and valleys on the lawn. Croquet is quite trying enough as it is, without being made more so.

"With regard to the change in the setting, I may mention one which 1 believe has only lately been tried, and which is thought by several players to be superior to the present one. In the hope that it will be more generally tried, I submit a diagram of it. It has been suggested to me that this setting should be tried in a small tournament later on in the year at Roehampton.... Yours faithfully, Charles Edwin Willis, June 14th, 1904."

This elicited comments in the issue of July 13th: "The setting proposed by Mr. Willis in the GAZETTE three or four weeks ago will be used this week in the Open Handicap Doubles at Roehampton. It is a modification of one which we have often tried in private, and at least has the merit of abolishing the turning peg. We think, however, that the introduction of new units of measurement, in addition to the familiar '7 yards, would be a mistake."

The Willis Setting meets with general approval, but not official adoption

And the 'Notes' were again devoted to the Willis Setting in the September 14th issue: "The 'Willis' setting, which was given a further trial in all events at Roehampton last week, met with very general approval. It certainly seems to possess many advantages over the old 'Hale' setting, which has so long been left undisturbed. It will be given another chance in the Open Doubles at St. Leonards, and we sincerely hope that at the end of the season it will be formally recognised, at least as an alternative setting.

"The advantages of the new setting are: (1) The 'Ladies' Mile' is abolished together with the turning peg. Thus breaks involve careful play throughout, and mistakes and inaccuracies are less easily remedied.

(2) The defense is strengthened; for the corner by the third hoop becomes as useful to the out-player as the first corner, formerly his only refuge in the early stages of the game.

(3) Wiring becomes decidedly more difficult. The double lines of wire pointing to the corners are abolished. Any double lines still left are either much longer or much thinner, and in other respects are harder to utilise.

(4) The winning peg being in the centre of the ground, the finish becomes much more difficult, safety being no longer insured by the old line of wire and wood down the centre of the ground. In addition, the solitary rover will get better chances of a reasonable shot at the peg.

(5) The setting is not too difficult for the moderate player. At the same time it is more worthy of the skill of the expert."

Despite all this, it was another 18 years before the Willis Setting was generally adopted in England.

[The preceding article was originally published in issue #203, May 1989, of England's CROQUET GAZETTE, and is reprinted by permission.]