|

Back to |

| The Front Page |

| Archives |

|

The SF Open, 1985 to 2000: a personal retrospective by Bob Alman; layout by Reuben Edwards; photos by Bert Myer, Mike Orgill, Dave Dondero, Marjorie Campbell, and anonymous others Posted August 17, 2000 |

|

||||||

When something you love passes away, an internal process ensues. There is grief, perhaps mixed with relief. You ask yourself "What does this mean?" You are driven to eulogize and significate. This is my eulogy for an event which I loved and which I helped to kill. You don't have to indulge me by sitting in your chair quietly and looking solemn. So if this oh-so-subjective recital strikes you as boring, I need make no apology - you can move on.

The San Francisco Open Committee voted to permanently retire the San Francisco Open after the 16th edition in May 2000. The tournament was at a pinnacle of its success as a three-flight American Rules tournament with a national constituency, having maxed out at 52 players six weeks before the start. Many have asked us why we would end a popular and successful annual tournament. I will not try to answer for the others on our production team. This article is my own personal response to the "Why?" question. The reasons we ended the Open are bound up with our reasons for starting it in the first place.

|

| Sheltered in the clubhouse from a day-long drizzle following the May 2000 trophy ceremony, the production team smiles goodbye: Wayne Rodoni, Karen Collingwood, John Taylor, Rosemarie Taylor, David Dill, Ed Breuer, Bob Alman, Elaine Fong. (Not pictured: Reuben Edwards.) |

I'll try to make my explanation factual, but the fact is that I take this event personally - it's creation, it's growth, and it's demise. I was there, all the way through, from the beginning.

In the beginning, everything was different. The national organization was only seven years old when the first San Francisco Open was planned for May of 1985. There were few clubs and players in the West and no USCA annual tournaments at all on the West Coast. The San Francisco Croquet Club was three years old and still playing on half a putting green - an area substantially smaller than a half court.

The club had been formed by socially prominent people in the San Francisco area, some of whom played very well for that time. Tom and Jane McDonnell were prime movers, along with Steve Swig and John Brown III. They paid a call to the general manager of park and rec. They carried some weight in this town, and they were given what they asked for: permission to play croquet every Sunday on half a golf putting green.

The space was approximately 90' x 50', and only approximately flat. But soon it overflowed with croquet enthusiasts, even though there was a stiff initiation fee of $300 and an annual membership toll of $200 - and this was back in 1982, when a buck could buy the Breakfast Special at the Tennessee Grill. The socialites welcomed into the club just about anybody who wanted to put up the fee. Mike Orgill and I joined at the same time, as we were the backbone and brains of the San Francisco Guerilla Croquet Club (a precursor to the "Xtreme croquet" movement - no-holds-barred croquet on any and all terrain, sometimes accompanied by alcoholic beverages.)

Hans and Vangie Peterson from Berkeley joined as well, and then Ed Breuer and John Taylor, and then Dave and Carol Dondero and Hood and Margaret Chatham.

|

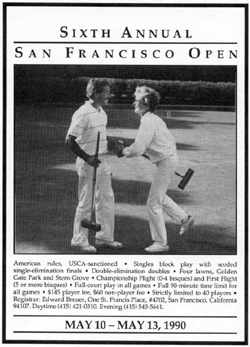

| The first SF Open tournament program introduced a now-famous logo that reflects the "high society" beginnings of a club that made its mark with public programs on municipal courts. |

It was about the time of the national political conventions of 1984 and the coronation of Ronald Reagan as the nominee for a second term that I got the idea for a "radical caucus" of the San Francisco Croquet Club to set a new course for the organization. In a spirit of fun, I called a meeting at my apartment of the "young blood", and we quickly came to agreement on our course of action. We would:

- not unduly alarm the old guard of the club and seek to enlist their support;

- vote into office only two new directors of the five (although we had the voting strength to take all five positions)

- empower me to do whatever necessary to get expanded playing space within the park system.

Soon the entire board was endorsing my ambitious efforts with the rec and park department. The radical caucus outlined our goals specifically to:

- seek two full lawns;

- institute a "public" policy that would impress the City: lower membership dues, free and low-cost events for the public; and a pledge to raise revenue;

- reorganize ourselves as a public benefit nonprofit organization;

- begin an annual "San Francisco Open" and invite everyone to come;

- teach ourselves to play good croquet and recruit and train promising players.

Most said we would never persuade the City to build and maintain two full-sized croquet lawns. It was unprecedented in America. There were no two-lawn municipal facilities for croquet, so why should this city be the first?

The answer to that question is too long to relate here and has been recounted elsewhere. By dint of sheer persistence, good luck, and a brilliant bureaucrat who enjoyed using his skill to create new enterprises in the park, our cause prevailed. It took several years, in which we suffered the consequences of severe vandalism, inexpert court construction, and even the seeming disdain of a national organization whose marketing focus at the time was almost exclusively on resorts and country clubs. The reorganized San Francisco Croquet Club - newly chartered on public turf with inexpensive dues to welcome all comers - did not fit the PR image around which the U.S. Croquet Association had been founded and promoted: croquet as a sport for the affluent class.

Most of us enjoyed our "black sheep" image within the USCA family. We were safely out West, after all, and there were no really good players out here. We were no threat to the established order. But at the same time, our ill repute and the rude things said about us in the East gave us motivation. We would show them! We would beat them at their own game!

|

| Character actor Maurice Marsac brought the mystery and glamor of the Beverly Hills croquet tradition to the Open in 1986. |

In January of 1986, we concluded our agreement with the San Francisco Recreation and Park Department granting us exclusive use of the two lawns on 19th Avenue, subsequently rebuilt. One of the two lawns was available for the 1986 Open, so we had abundant space for our 35 players, still using the only format we knew: double-elimination; in '86, we split the field into two flights. Canadian Reid Fleming won the Championship Flight and then went on to win the USCA Nationals.

Nobody came from the East Coast

Still nobody came from the East. Reports from Florida dubbed us the "San Francisco roughnecks." We were still on the far western frontier, while all the serious action was on the East Coast. More than once I heard Easterners opine that you could never learn to be a really good player on public turf. And all the while, we were faithful, due-paying members of the USCA. Our SF Open kept growing as the main West Coast American rules annual.

In 1987, the second 19th Avenue lawn had to be opened prematurely following rebuilding and a series of mishaps with the leveling and planting. We referred to it as "the sand pit," and we had to use it. It had not even been cut until the day before, when John Taylor, the tournament director, pretending nothing was amiss, brought out his hand mower and gave it the once-over. I am sure there has never been a tournament lawn in worse shape. But the players were most polite. Nobody complained. Everybody had the same disadvantage, after all. And this WAS the San Francisco Open, the best annual on the West Coast.

Five lawns put us in the big leagues

|

After the 1987 sand pit experience, everything got better and bigger. Following a long and bitter political struggle against the lawn bowlers, the Recreation and Park Commission granted our request to rent three bowling greens in Golden Gate Park for $100/day per lawn. All of a sudden, we were big time! A five-lawn tournament, no more half courts! We spread the word. We expanded our tournament to four days. Our tournament had come of age in just three years.

Forty-four people came in 1988, some of them from long distances, but still none from the East. Nevertheless, some very good players were competing now. Neil Spooner was the pro at Sonoma-Cutrer, which had opened in 1986. He defeated Garth Eliassen in the final of the 1987 SF Open.

In 1988, we added doubles.

In 1989, we had the first major influx of the Internationals - the players in the Sonoma-Cutrer Worlds who wanted to "warm up" in the American rules SF Open. National Champion Reid Fleming beat Irishman Simon Williams in the final, while Tony Stephens of New Zealand settled for third. Local players - from Sonoma-Cutrer, Meadowood, and San Francisco - began to make their mark. By the late nineties, we were tarred with a new epithet from the East: "Western killer players." It wasn't said with respect, but it showed they were taking notice of us. We wore the "Western killer" sobriquet with pride.

Killer players on public courts earn some respect

By 1990, our first homegrown star had begun to make his mark. Wayne Rodoni made it to the finals, where he was beaten by Australia's Barrie Chambers. Eastern players started showing up. Word was spreading.

Tony Stephens scored his victory in 1991, beating Chambers.

In 1992, another San Francisco Croquet Club rookie, John Taves, streaked into the finals, delivering another defeat to Chambers.

With the introduction of the third flight in 1993, the tournament achieved its full dimensions. More Easterners came in all three flights, some year after year.

|

| In the early nineties, two national champions owned the doubles title: Wayne Rodoni and Reid Fleming are a study in outplayer concentration. |

In 1995, Taves won the SF Open, while Rodoni took the National Championship. In 1996, Rodoni posted his second singles win in the Open.

By 1996, the two "practice days" before the four-day tournament proper were popular and well-attended. The tournament calendar was full of social events and the block-and-elimination format was popular with the players: we made sure, most years, that at least two-thirds of the players made it out of the blocks.

In the final four years - 1996-2000 - Mik Mehas of Southern California showed up in the finals. He was beaten twice by Dr. Carl Hanson of the SFCC; but finally won the winner's title by defeating Dr. Carl in 1999, then repeated in 2000 against John Phaneuf.

Sixteen years. In the course of those 16 San Francisco Opens, while we learned to play croquet and produce events, we had seen the entire American croquet culture change. We were no longer on the far Western frontier; municipal clubs, no longer a rarity, were embraced by the USCA establishment.

The tournament we had begun as a lone Western imitation of Eastern tournament formats was joined by other thriving West Coast tournaments in Seattle and Vancouver. We had done everything we could do with the San Francisco Open. For all this time, we largely resisted the temptation to do other tournaments and other formats: one full-out effort from our team each year was enough. We felt we had to maintain our standards. We didn't want to go backwards.

There was finally the dawning realization that we were stuck. There was nowhere to go. Ed Breuer (the traditional registrar) said the unthinkable a couple of years ago: "We could just stop doing it." I admit I was shocked at the suggestion. Wayne Rodoni wasn't shocked. His impeccable court settings and equipment management contributed a lot to the reputation of the tournament. But he had stopped most competing and had gotten married, so his values had changed. He didn't need this, he was going along to be a good guy, not to let us down. John Taylor was sometimes on the team, sometimes off, depending on how much trouble we gave him in seeking a "perfect schedule" for our tournament - so he didn't have a vote. Karen, Elaine, and Reuben had come into the equation fairly late and were nowhere near burned out - but if we wanted to call a halt, they would, too.

Gradually, we warmed to the idea that we could actually end the tournament at a high point - while we were still ahead of the game. Best of all, that would open up space to do other events here, in different formats.

So we had a meeting. We voted. It was unanimous. No more San Francisco Open. We announced it formally and sent letters of explanation composed by Ed Breuer to all the recent players. Breuer summed it up this way: "By the year 2000, we had done almost everything we could do with a four-day, three-flight American Rules event on five lawns. So we've decided to retire the San Francisco Open while it is at its best."

And that's the truth. Not everybody's truth, not the whole truth, but pretty close.

The response to our announcement was heartwarming. Many players wrote to us expressing regret. We promised them that althought the Open was over, croquet in San Francisco was definitely not over. They could come again and play with us in other tournaments. Good tournaments, well-organized events. We promised.

Almost instantly, enticing possibilities presented themselves. We were asked to host in 2001 the North American Open. This tournament - the strongest International Rules event in the US - was begun several years ago in Phoenix by Jacques Fournier. I think we'll probably do it. We have been asked to produce the 2001 Western Regional; and I think we'll probably do that, too. We could have simple, "no-frills" two- and three-day tourneys for players in the area. We could host another national tournament or two. We know how to do all that. So I think we'll do it sooner or later, all of it. (But I can only speak for myself.)

Producing a good tournament is like giving a good party. Aside from everything else, there's a certain satisfaction in planning a good event, sending the invitations, having people actually come to the party, and then tell you they had a good time. I'll miss that if I don't do it again from time to time. I think most of the other team members feel the same way.

The summing up

Any reasonable person would have to cite weather as a good reason for retiring the Open. For the first Open, Orgill, Alman, and Peterson somehow determined that May would be the best month for the event - May, when the lawns are at their finest and the weather is mild and dry. Wrong! The only thing unpredictable about the Open's May weather has turned out to be exactly what kind of unpleasant conditions will prevail: Freezing 50 mph winds? All-day drizzle and fog? Rain? All three at once? Could global warming be the cause? Has May ever been a good month in San Francisco? It's hard to say.

Although many players from the East competed in the San Francisco Open, no Easterner ever claimed the championship. This year, for the first time, an Eastern player made it to the final: John Phaneuf of West Palm Beach. Mik Mehas defeated Phaneuf to win the last Open. Other past champions include Sal Esquivel, Reid Fleming (three times), Neil Spooner, Barrie Chambers, Tony Stephens, John Taves (twice), Reginald Bamford, Wayne Rodoni (twice) and Carl Hanson (twice). All the biggest croquet-playing countries are represented in this international players "hall of fame" except England and Ireland. World Champion Robert Fulford was dispatched by South Africa's Reg Bamford in SF Open of 1993, while Reid Fleming of Canada beat Simon Williams of Ireland in 1989's final.

The SF Open champions who learned to play croquet in San Francisco have all distinguished themselves in other major national and international tournaments: Sal Esquivel was an early winner of the US Open; Wayne Rodoni was the club's first American Rules national champion in both singles and doubles; John Taves, captain of the American team in the most recent MacRob, has performed consistently well in many international matches and today is the top American in the World Rankings. The newest club champion, Dr. Carl Hanson, who defeated Mehas twice consecutively in the Open final, will be a threat when he can spare the time to play in national championships.

In SF Open doubles, Wayne Rodoni must surely qualify for some kind of record in a major annual, winning nine times beginning in 1990, with three different partners.

All the presidents of the USCA made their pilgrimages to the San Francisco Croquet Club. Jack Osborn, founder of the USCA and a native San Francisco, came before the Open was organized to produce the first Western regional on San Francisco's "hill courts" in 1982. He is the only USCA president never to have played in the Open. Foxy Carter turned blue in freezing winds in Stern Grove, bundled up in overcoat, scarf, and gloves. North Carolinian Bill Berne was a perfect gentleman in the face of rude remarks thrown his way by passing rowdies over the barrier fence around the bowling greens in Golden Gate Park during a doubles game with his wife Billie Jean - because of his southern accent, we presumed. Dan Mahoney came twice and cheerfully failed to advance to the final rounds.

Croquet mixed with "real life" in the big city

|

| Not until its third year did the Open suffer truly bad weather - the dense fog and all-day drizzle that revisited the event often in the 90's. |

The San Francisco Open was known for experimentation and innovation. We enjoyed doing new things in the club and in the tournament. In the last two years, the main innovation was the introduction of games-to-the-peg (no time limit) in the elimination ladder of the Championship Flight. The experiment was enthusiastically embraced by the players, and the worst fears of the organizers were not realized. The longest game in the ladder was 121 minutes; the shortest was 61 minutes.

In the last Open, we discussed for hours upon hours the possibility of being the first major tournament to experiment with multiple ending rotations after time - known as "Wharrad turns." But we couldn't figure out an equitable scheme to do this for all three flights - and treating all the flights equally has long been a quality standard of the San Francisco Open.

We started the Open trying to prove something to a croquet establishment that seemed to scorn us. The Open was central to the growth and development of our club. But that is long past. We have nothing to prove now. We are now part of the establishment, and our players have helped to shape a new image for the sport, moving it - if only by inches - towards the mainstream.

And here's my final personal truth about the demise of the SF Open: the new frontier of American croquet is no longer way out west; oddly, it has moved back East, back to Florida, back to West Palm Beach. All the experimentation and innovation we wanted to do here will be multiplied ten times over at the National Croquet Center. The modest San Francisco experiments in public court programs will be duplicated and expanded at a National Center which will provide lawns not only for the country's finest resort-class club, but also for public and corporate groups to provide as many workable models as possible for marketing the sport more broadly throughout the Americas.

The San Francisco laboratory of events, programs, and formats has been shut down. It is no longer needed.

But I digress. My eulogy has lapsed into reminiscence of the past and speculation about the future. The Open is over. Why? Because it's time to do something else. You'll be invited.