|

Back to |

| The Front Page |

| Archives |

AFTER IT'S OVER:

THE BIRTH OF A MILLENIAL

VISION FOR MACROB 2000

by Bob Alman and Mike Orgill co-editors of CROQUET WORLD Online Magazine

-

The U.S. could put a man and woman on Mars by the year 2000, and America could displace Britain as masters of the sport of croquet within the next four years. It's just a matter of priorities.

On July 4th, after three grueling weeks of play, the order of finish in the 1996 MacRobertson Shield was exactly as the smart money predicated. One of the biggest stories was the significant improvement in the American team over their poor debut in the competition in 1993. Nevertheless, the Americans still finished last in the 1996 MacRob, raising the question: How can American players and the United States Croquet Association avoid the "wooden spoon" - fourth place - in the 17th MacRob in the year 2000?

GREAT BRITAIN SETS THE STANDARD

The Great Britain team showed consumate mastery of the sport and has set standards in MacRob 1996 that must be met by any serious challenger. The relative strength of the teams are revealed in these statistics, mirrored in the order of finish:

Matches Won Triple Peels

Great Britain 40 57

New Zealand 31 24

Australia 27 25

United States 17 7

"Matches won" shows the overall results; "Triple Peels" indicates the

level of tactical refinement needed to excel in the sport at today's highest

level - certainly not the only measureable level of refinement, but serving

well enough as an index to future improvement.

AMERICANS SHOW PROMISE

Only now that the 1996 MacRobertson Shield has passed into history can

the prospects for MacRob 2000 in Australia be honestly confronted. The

U.S. made a predictably weak showing in their first MacRob in 1993, winning

only three games (all against the second weakest team, Australia) and no

matches. Going into MacRob 1996, the team hoped to make a better

impression, win a number of matches, and show significant improvement.

That, it did, especially in the series against New Zealand.

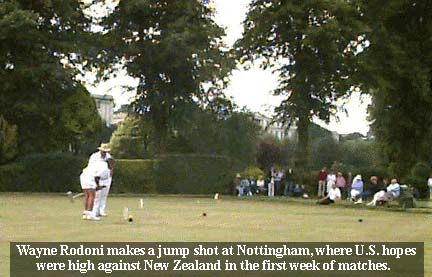

The test against New Zealand in the first week, when

the U.S. rolled up a good lead before finally succumbing by a 12-9 score,

provided a tantalizing glimpse of the possibility: actually winning a test;

maybe two; or at the outside, actually winning the MacRob in the

third try. (It took New Zealand four tries to win it, on home turf, in

1950.)

So let all aspiring team members for the MacRob 2000 know at the outset that

their croquet fans will want them to win it all in 2000. That's an

unreasonable expectation, but it has been given birth by the fighting spirit

and fine performance of the American team of 1996.

YES, IT'S CONCEIVABLE - BUT IS IT REALLY POSSIBLE?

The question is: How will the American players develop the skills

necessary absent the close-knit competitive environment that exists in

England, and New Zealand? Distances in England and New Zealand are

short, where all the top players are in range of all the top tournaments,

whereas in America distances are vast, top players are isolated one from the

other, and going to every event (as few as they are) where other players will

test and challenge your skills is a hardship.

Make no mistake, however. The American Shield team showed that the

promise is there. We have several players who performed well under the

exquisite pressure of the MacRobertson Shield.

YANKS TO WATCH

Jerry Stark of Santa Rosa, California proved once again that he is a highly

accomplished performer who thrives in big competitions. He must be the

cornerstone of any future U.S. team. Wayne Rodoni is rapidly becoming one

of our three best international players, and Erv Peterson continues to

show the competitive consistency that is such an important factor in

selection.

All these players embody that rare combination of skill, ambition, and

discipline that impels them to continue to hone their skills, even if they

have to do it alone on the practice field. But they can't fully develop

their potential without regular peer competition.

Britain and New Zealand enjoy the advantages of close-knit croquet

communities. By contrast, promising players in the U.S. and Australia may

have little chance to develop properly unless they happen to live near a

regional "center" of croquet players, and those centers are few and far

between.

Consider the example of Jeff Newcombe, whose star rose quickly in Western

Australia, separated by thousands of miles of wilderness from the

below-scratch players he would need to play regularly to develop to his full

potential. He is now, by a long shot, the best player in Western Australia.

But in Perth, absent the established culture of top croquet players on the

eastern edge of the continent, he will need enormous discipline to maintain

and refine his game. His situation is parallel to that of John Taves,

peerless in Seattle, needing to carefully ration his croquet travel time in

balance with family and business obligations.

SO MUCH TERRITORY , SO LITTLE CROQUET

In the San Francisco Bay Area, a virtual hotbed of top-level croquet, and

home of four of the six 1996 MacRob team members, three clubs

constitute the entire constellation of Bay Area croquet power. (Stark is

the pro at Meadowood in the Napa Valley; in the adjacent Sonoma Valley,

45 minutes away, lie the two perfect lawns of Sonoma-Cutrer, home club

of Peterson and Rebuschatis; sixty miles south is San Francisco and the

home turf of Wayne Rodoni (where Taves first made his mark as a

precocious rookie).

But in all of California (an area twice the size of Great Britain) there are

only three events a year where a number of top players come together to

complete in the International Rules game: the Sonoma-Cutrer World

Singles Championship (where only a few Americans are allowed to

compete); the U.S. Open; and the California State Championship (perhaps

the only USCA sanctioned state championship with the top flight playing

International rules).

Besides those three events, there are only two other events in the

entire country drawing a significant number of top players in the

International rules game - the USCA International Rules National

Championship, and the Chattooga Challenge (which combines International

and American rules play). invitational annuals in Delaware

and Virginia draw a limited field of good players. (Last year east and

west coast selection tournaments were held by the USCA, but none are

scheduled for 1996.) Even if all the top U.S. players could compete in all

seven of these events - which they most certainly can't because of a

combination of time/distance/expense - it wouldn't be enough to provide the

training and exposure they need in top-level play.

TRIPLES ARE MANDATORY

The truth is that the best U.S. players can still win any one of these

events without having to consistently attempt triples. In a competitive

environment which demands triples does not exist in the U.S., where and

how will our players advance in their skill levels to the highest world

standards in the sport?

From John Taves' remarkable rookie win in the 1991 U.S. Open to Mike

Mehas' Open victory in 1995 there has been a clearly discernable and

steady improvement in the skill levels and tactical refinement of Americans

in International rules tournament play. One factor that strongly

reflects this improvement is the increase in triples from 1991 to 1995. In

1991 the triple was a refinement with which Americans were not comfortable,

so they seldom attempted it. In 1995, the triple was still not attempted

by everyone, but it had become the way to win.

Such measures prove that Americans are getting better at International rules

play. There is no proof, however, that American croquet has achieved a

"critical mass" of competitive momentum to carry a "new and improved" U.S.

team to victory in MacRob 2000.

PRESCRIPTION FOR VICTORY IN 2000

What would it take to improve International rules play and field a U.S. team

capable of taking the Shield away from Great Britain? The

most straightforward way would be to create more prestigious International

rules tournaments and encourage International rules play at clubs by

publicizing and perfecting the separate handicapping system which already

exists; to establish International rules training

centers for interested championship-level players in all regions; to

acknowledge that the only way to approach the top world competitions as a

feared and worthy opponent is to embrace International rules, not just

offering it as a "flavor" for those adventurous enough to try it.

International might even be used as the principal introductory or training

game, with American rules brought into the curriculum later, when a player

can run three-ball breaks. The shotmaking skills essential in International

Rules will be developed first; the mental complexities of American rules

strategy would follow.

CULTURAL CHANGES HAPPEN SLOWLY, IF AT ALL

The most straightforward and logical step, however, is often the most

revolutionary and unpopular. There is tremendous resistance to

International rules play in many if not most regions of the U.S. Those who

"grew up" with it relish the American rules games with all its brain-bending

strategic challenges, and quite rightfully, in their minds, regard this

"foreign" game as not suited to the American style of play and the American

way of thinking. This was the position of Jack Osborn, founder of the the

USCA; it is still the position of many avid players, not just on the east

coast, but wherever USCA croquet is played.

This belief in the unique values of the American rules games is fundamental

to the culture of croquet in America. Changing that fundamental belief,

even if it were desirable, might not be possible. It is just too radical -

as radical as going to New Zealand, for example, and proposing that all the

clubs buy deadness boards and teach their novices to play USCA croquet. It

might be a wonderful idea, but you can bet it couldn't and wouldn't happen.

In North America, the American rules game will remain as the dominant game

because the entire culture of American croquet is built around it. So the

development of a winning U.S. team will have to be undertaken on top of the

existing culture, if not at odds with it.

ORGANIZED PLAYER DEVELOPMENT W0ULD HAVE TO BE FUNDED

Even more perplexing, when faced with the challenge of actually organizing a

national player development program, are the problems of organization and

funding. While sports in the Commonwealth countries, including croquet, get

substantial government funding and other incentives, any organized initiative

in the U.S. must continue to be entirely "privatized." (U.S. Team Captain

Jerry Stark raised more than half the substantial funds needed to send the

team to England by appeals to corporate sponsors associated with events at

Meadowood Resort in the past.) Having an American team win the MacRob in

the year 2000 calls for an organized, sustained, and well-funded effort

comparable to "putting a man on the moon." It doesn't just happen by

itself. Given the USCA's failing fortunes, it is unlikely that anyone in

the American croquet scene is willing or able to marshall the resources

needed to spearhead such an effort.

However well funded or organized, developing the player power needed to win

the Shield requries more Americans learning and playing International rules,

more people playing in international tournaments, more rookies concentrated

on making and playing breaks, not just "saving deadness" on the boundaries

and in the corners.

In spite of the difficulties, a few players have made themselves good

candidates for top-level international competition. This small talent pool,

little more than a score of below-scratch players, must be nurtured with

organized training and better opportunities to compete at top level.

Imitating our Commonwealth friends, America could have its own President's

Cup for the top eight players, as well as competitions for the

next eight, and the next eight, and so on - anything to build the tournament

toughness needed to win the Shield - if (and it's a big "if" ) excelling in

international competition is to be a genuinely important goal of the USCA.

REFINEMENTS OF THE GAME: "POP" TACTICS

The British showed us a thing or two about strategy during the latest

Shield, and American players would be well-advised to practice what their

masters have taught.

Robert Fulford, quite simply the best there is, employed some

impressive tactics - called POP tactics - in the Shield that are anything

but new, however seldom seem. Keith Wylie promoted them more than ten years

ago years ago in his classic book, "Croquet Tactics." POP stands for "peel

on opponent." If you are playing at the high levels common in International

croquet your opponent is likely to finish with a triple peel if he goes

around first and you miss your lift shot . If you hit your lift and go around

to four-back in turn, you still face the prospect that your oppoent will more

than likely finish the game with a triple if he hits in after your turn. The

POP scheme is to peel your opponent's back ball through the first and second

hoops while you make your break to four-back. The theory is that you will

make the opponent's triple much more difficult, securing for yourself an

additional lift shot and therefore a bigger chance to win the game.

As Wylie puts it: "You get the most out of POP tactics when the standard

[of play] and the state of the court are such that the peels you do

significantly reduce the likelihood of lthe opponent] being able to win in

two turns."

Americans must seriously consider POP tactics and other styles of play that

"stretch the envelope" if they are to prevail in the rareified heights of

International croquet.

CAN AMERICANS SURVIVE CROQUET MARATHONS?

Strategy and tactics aside, there is one haunting doubt: Even if the

number of tournaments gathering together top players were sufficient to

fuel the necessary advancement of skills, where will those players find

anything resembling the sheer intensity of the experience of playing in a

21-day event, up to three games each day, often lasting 10 hours or more?

The longest known tournament in the U.S. has been 10 days, with nothing

like the sustained play of the individual competitor necessary in the

MacRobertson Shield.

How does one cope with so much croquet packed into so many continuous

days of top-level, pressure-packed competition? How could one prepare

for such a thing in the more laid-pack pace of U.S croquet? The

exceptionally fine performance of the U.S. team in the first week, against

New Zealand, might be explained within the context of the entire 21-day

ordeal: How could anyone endure so much croquet at one go? The next

American MacRobertson team should try to answer that question as well.

The 1996 MacRob revealed, in the final statistics, that at least two of the

U.S. team members thrive on sustained competition and improve in the course

of it: The top two performers on the U.S. team overall, Taves and Rodoni

(well known as a "slow starter), turned in their best performances in the

final week, between them bagging five of the seven U.S. match wins for the

week.

PLAYERS FOR THE FUTURE

Four more years. No doubt, the top performers in each of the teams will

be urged to represent their country in New Zealand in the year 2000. Fulford

will be back, surely, and Cornelius, Maugham, Clarke, Skinley, Pickering, and

Tony Stephens. For the U.S., one can easily see Rodoni, Stark, Taves, and

Peterson playing in the next MacRobertson.

Wayne Rodoni will continue to improve, steadily, as he has assured us in a

recent interview (See "Courtside Chats with MacRobertson Players" at this

Website). John Taves is the fastest rising star in American croquet, and

he should surely be a selectee in the year 2000. Team captain Jerry Stark

has more than paid his dues with the best record of any American in top-

level interntional competition over time. Erv Peterson's consistent,

workmanlike performance may well qualify him for another team spot.

Among the major performers in the U.S. who were not on the 1996

MacRobertson team, one must put at the top of the list Mik Mehas of Palm

Springs, California, and Phil Arnold of Santa Rosa, California. Arizona,

with the help of the Fournier tribe, might produce future team members. The

croquet boom in the Southeast and South Atlantic states may yet spawn a new

generation of champions to take the place of America's first champions, who

all came from that region.

In the next four years, there will be many new rookies whose names we have

not yet heard. America's first, halting steps in the "Olympics" of croquet

has shown them a possibility. They will be reaching for the highest prize

in the sport: an invitation to be on the MacRobertson team.

The team will be reaching for the Shield itself - and it really will be a

reach. It's an extravagant vision, brashly American - a vision worthy of

the millenium.

John Taves of Seattle is one to watch. In the short space of three

weeks, Taves showed increasing sophistication, as noted by British

commentator Brian Storey. He thrives on competition, he was

strenghtened rather than daunted by it, and he accomplished three of the

Yanks' total of seven triples in the event. (Stark also had three, Rodoni

one.)

John Taves of Seattle is one to watch. In the short space of three

weeks, Taves showed increasing sophistication, as noted by British

commentator Brian Storey. He thrives on competition, he was

strenghtened rather than daunted by it, and he accomplished three of the

Yanks' total of seven triples in the event. (Stark also had three, Rodoni

one.)

For an intimate insight into the thinking of some of the top performers

of MacRob 1996, see: "COURTSIDE CHATS WITH MACROBERTSON PLAYERS" at this

Website.