|

Back to |

| The Front Page |

| Letters & Opinion |

|

Croquet in print advertising

|

|||||

|

by James Hawkins

layout by Reuben Edwards Revised and updated April 7, 2005

|

|

||||

James Hawkins, the youngish retiring editor of the English Croquet Gazette, began to acquire American croquet-themed print ads only a few months ago, and his burgeoning collection now numbers 44. With tongue wholly and firmly in cheek, he writes, “I’ve realized I can refer to an ad as being rare or valuable and do so with confident authority. As I’m the only purchaser of these things in the world, I feel it’s entirely appropriate for me to dictate the sentiment of the market. These items don’t warrant a high monetary value at present, but once my article is online, maybe the speculators will move in and we’ll find ourselves sitting on a nice nest-egg.” In the meantime, we can admire these vintage images and pine for a once and future era when croquet ruled in the backyards of America.

|

Few things act as a better indicator of social history than advertising. Marketers sink vast sums into reaching an audience, and their intention is to strike a chord with as much of their target group as possible. So croquet’s elitist, aristocratic image seems to be at odds with the populist needs of advertising.

The game’s always had an immediate recognition factor - everyone knows what croquet is - but that recognition (these days, at any rate) comes with all those uncomfortable preconceptions of class. With just a split-second in which to grab the viewer’s attention, few contemporary advertisers would touch croquet with a bargepole.

|

| BROADBEAD, circa 1880. This is the oldest image in the Hawkins collection, circa 1880. |

It’s a great surprise, then, to see so much advertising memorabilia featuring the game. Most of what survives is print advertising in magazines, and most of that comes from the USA, in the first decade after World War II.

|

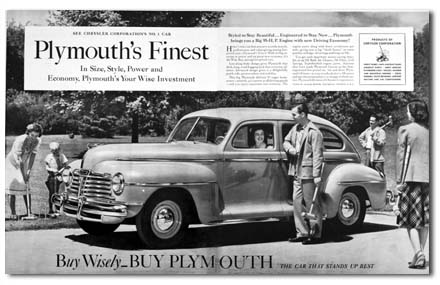

| CRYSLER-PLYMOUTH |

Those were times of increasing prosperity. Families were settling down, consumer spending was up, and leisure time was on the rise. Croquet fitted well into this environment. In the eyes of advertisers, the game became a symbol of aspirations towards domestic bliss. We see images of family barbeques, family picnics and family garden parties. Now that beer producers were marketing their wares to the stay-at-home family man, the idyllic representation of croquet was ideal.

Those were times of increasing prosperity. Families were settling down, consumer spending was up, and leisure time was on the rise. Croquet fitted well into this environment. In the eyes of advertisers, the game became a symbol of aspirations towards domestic bliss. We see images of family barbeques, family picnics and family garden parties. Now that beer producers were marketing their wares to the stay-at-home family man, the idyllic representation of croquet was ideal.

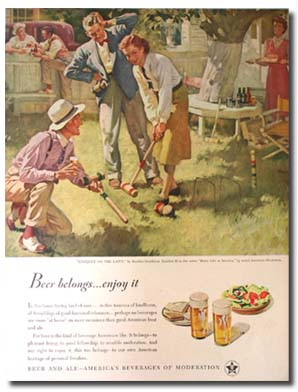

The United States Brewers Foundation churned out hundreds of ads, aimed at getting bottled beer drunk at home. Their “Beer belongs ... enjoy it” campaign of 1948 featured many domestic scenes, two of them incorporating a game of backyard Croquet. (Croquet comprised a tiny section of the output of the series, which ran for another decade. Later examples include No 53: “Dad tries out the ukulele”, and No 106: “Showing off the new kitchen”.)

Taking their lead from that campaign, Anheuser-Busch, the manufacturers of Budweiser Beer, kept Croquet in the public eye with a series of adverts that ran until 1952.

|

| BEER BARBEQUE |

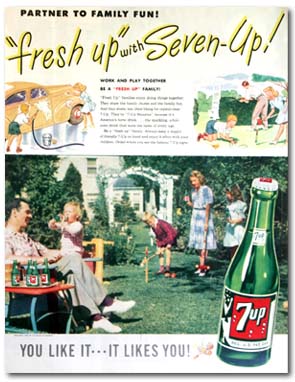

Soft drinks advertisements, though fewer have survived, portray the same domestic scene. One early instance is the 1947 Seven-Up campaign - children play a game while the adults enjoy the family gathering. Colour printing was becoming common in the late 1940’s, but colour photography in print was rare. Where other ads used commercial artists for illustrating, this example stands out for its early use of photographic images.

|

| SEVENUP (1947) |

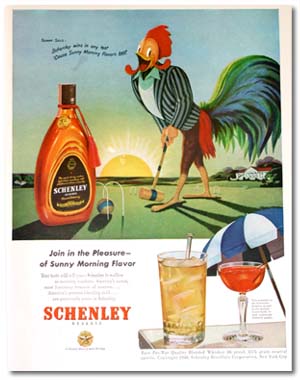

Croquet lent itself to several whiskey advertisements of the era. Schenley Reserve (1948) is a good example (“Schenley wins in any test/’Cause Sunny Morning Flavor’s best” ran its slogan, though its implicit encouragement for breakfast-time drinking might raise eyebrows now).

|

| Schenley Reserve (1948) |

Adverts of the time are run through with a secondary theme of nostalgia. As a young, rapidly expanding country, the United States had little in the way of tradition. By 1950, croquet may have become an aspirational pursuit for nesting families, but it also carried the imagery of an old game.

Brands like Budweiser wanted to show their age and experience. Their centenary in 1952 was marked by another croquet campaign, featuring whiskered gentlemen in blazers and boaters engaged in play. No matter that croquet wasn’t introduced into North America for another decade. Facts were bent even further by Royal Crown Cola in 1945. In 1831, the story goes, Cyrus McCormick of Rockbridge County, Virginia, invented America’s first mechanical reaper. When the going got tough, he relaxed by playing croquet. By analogy, millions of shrewd Americans know that a quick cola break improves productivity for the war effort.

|

| ROYAL CROWN COLA (1945) |

|

| TAMPAX |

Pre-war adverts featuring croquet had concentrated on the game itself: croquet sets for sale, and outfits for ladies to wear. The consumer boom had seen a much less literal use of imagery, and croquet was popping up in advertisements for all manner of products - soap, dog food, sticking plasters, vitamins, cars, fashion and shaving foam. The heyday of magazine advertising seems now to have run its course, and it’s difficult to see where Croquet would fit in with current thinking among marketers.

That’s not to say that the game’s vanished from the advertising radar. Anchor Foods sank some money into croquet in the late 1980’s, in order to help launch a new product. The accompanying TV campaign showed the family butler serving Anchor’s sophisticated new fruit cordial at the country house croquet party. The product failed to catch light and was soon withdrawn.

Yet more recently, the beleaguered Abbey National re-branded itself with a series of cuddly TV ads, to show the world that everything was fine in retail banking. Computer graphicked images of dog walking and kite flying accompany soothing music. Blink and you’ll have missed the woman playing croquet. And now that Abbey has been devoured by Banco Santander, you’ll not see it again.

Clarks Shoes are more on the ball, and know that the eccentricity of croquet doesn’t mix with mainstream advertising. Last year they ran a campaign featuring the San Francisco Extreme Croquet Club. You’d have to have been sharp-eyed to catch their series of point-of-sale posters and Internet content. Boring old Association Croquet would have been a bad proposition for them, but allying their own boring old brand with something so self-avowedly off-the-wall certainly did them more good than harm.

|

| San Francisco Extreme Croquet Club |

It’s one of the unexpected knock-on effects of the Internet age that a strange cottage industry has been born from the buying and selling of vintage advertisements. Vendors buy old magazines by the dozen, and cut out the interesting adverts. Websites such as eBay (www.ebay.com) act as intermediary for the online auctions which ensue, though croquet makes up such a small niche market that supply far exceeds demand.

A new collector after vintage advertising material shouldn’t have to look very hard, as fresh lots appear on eBay almost daily. With a weak dollar, items priced at $2.50 seem attractive indeed to British purchasers. Alas, there’s no easy pricing formula. Budweiser ads seem very common, reflecting the media-buying power of a major brand and the large print run of the titles in which they appeared. Collectors should be prepared to pay around $10 for some ads (such as my Schenley Whiskey ad), purely because Coca Cola collectors will be bidding for the reverse side. But it’s now my prize possession.

Here I’ve let it slip - I’m addicted to the collecting game. I guessed there’d be only a handful of items out there, but, a few months later, I’m knee-deep in memorabilia. As high art, perhaps, two talking cows on a 60-year old advert for health drinks may not amount to much. I can’t get enough.