|

Back to |

| The Front Page |

| Letters & Opinion |

|

A critique of THE BALL: Discovering the Object of the Game by Bob Alman posted April 12, 2013

|

||||||

|

||||||

One ball. Opposing teams. A goal. Passionate spectators. Hard play and fast action. Consequences for winning and losing. These primal elements of the most popular spectator ball games have changed little over the last 3,000 years, whether played by "ordinary" citizens in remote British villages with the opposing goals ranging from the bishop's doorstep on the hill to the dock on the harbor; or by professional athletes with multi-million-dollar contracts for games played in huge stadiums and televised around the world.

A simple question of the seven-year-old son of John Fox prompted his years-long odyssey around the world and over eons of time to find an answer: "Why do we play ball, Dad?" Fox seemed to enjoy his ensuing global rambles in search of an answer a little too much. He lost focus. He would have been better advised to limit his inquiry to just one kind of ball-game--the kind played by gladiatorial teams contesting territory and focused on one ball as the single "object" of the game for both opposing sides.

Fox could have begun with the ancient game of ulama in central America, progressed to "street-ball" in medieval times and still passionately contested by different neighborhoods on the isle of Orkney, and continued with the modern development of football, soccer, hockey, and lacrosse And he could have justified including basketball and box lacrosse, both invented in modern times to be played indoors in cold weather.

|

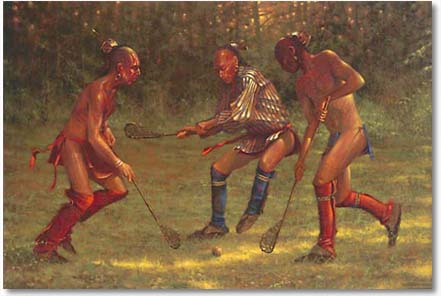

| Lacrosse was perfected by the North American Indians long before Europeans arrived, partly as a method of settling inter-tribal disputes. Their wooden stick with a pocket for the ball added velocity. Until well into the 20th Century, the native American Indians most expert in the game were not allowed to play in the major leagues in the U.S. and Canada. So like the African-Americans, they formed their own sports leagues. |

But he didn't do that. Instead, he included all sorts of ball games which do not encourage or permit contact--such as baseball--and some which have no element of team activity and no trace of primordial roots in tribal warfare, such as tennis. He included baseball, I think, because when you write a book in America about THE BALL, how could you justify leaving out what is considered by many the quintessential American sport? (That's what I guess his editor might have asked.) The reason for including tennis is probably his self-confessed love of the game, from early childhood.

To his credit, he did not include golf or any form of lawn bowls, or croquet, but in an appendix labeled "Outtakes" (presumably because it didn't fit into his scheme for the book) he does describe bocce, beginning with this single--and insulting--comment on our favorite sport: "To be honest, I'd never taken bocce seriously as a sport. Like croquet and horseshoes, it always seemed like a social activity designed to keep your other hand occupied while drinking beer."

Horseshoes! With that absurd comparison, Mr. Fox proves that he is unaware that unlike baseball, mostly confined to the Americas, croquet is now a well-organized and regulated worldwide sport, and one that most certainly cannot be played well with one hand!

American exceptionalism certainly plays a part in the Fox selection of coverage, because not only does he devote much space to the "American" game of baseball, actually derived from stick-and-ball games in Britain including cricket, but he also dwells on the particularly violent and dangerous form of American football similarly unseen in most other countries of world, where soccer is overwhelmingly the "football" of choice.

"Why do we play ball?"

Although Fox has achieved eloquence in describing how balls have been made in the past and how they are made today; and how ball games divide and bring us together, ground us in timeless traditions and connect us across generations, bringing out the best and the worst--love and loyalty, violence, deception; and although his research across the globe has yielded some interesting stories about all those games as they have evolved over millennia, he doesn't offer a really satisfying answer to his son's question. Finally, it's left to his son, seven years later, to answer the question himself: "We play ball for the fun of it."

|

| Soccer improved upon the ancient Mayan game by enlarging the target and having it defended by a human goalie who, however, cannot be legally put to death for failing to defend the net against the enemy's winning point. |

And so do all the higher primates, apparently, and many of the mammal species, including dogs who instinctively seem to "enjoy" retrieving ball, and dolphins who can do amazing tricks with soccer-like balls to entertain human audiences.

For the most part, Fox does limit the scope of his inquiry to one kind of ball game: in which the ball, as the central focus, is contested by teams facing each other in a territorial contest scored by one team reaching a target in the enemy's territory. Games in which the balls are struck with sticks are also included, allowing for baseball, lacrosse, and hockey.

The best speculation is that these games and many others were first contested by innumerable "players" on either side, on unmarked territory or grounds circumscribed only by natural boundaries. It's only in fairly modern times that the "courts" or "fields" were standardized (often to facilitate spectator galleries) and the opposing players limited to an equal number on both sides.

|

| The joy of professional footballers everywhere after a big win is as well justified as that of the fans: bonuses and renewed contracts. These Liverpool players are not faking ecstasy in the moments after a significant 2005 victory. |

Despite the gaffe on croquet, the Fox book appears to be well researched, documenting the ubiquity of ball play throughout the known and imagined history and the prehistory of our species. In dutifully researching his topic in the other sciences, Fox is willing to leap heroically to sweeping and sometimes astonishing conclusions.

He convincingly advances the theory that the development of a human's ability to throw a rock, in order to hunt more efficiently, was the first step of early man towards the modern world of homo sapiens. He even cites the research of the evolutionary biologist William Calvin, who believes "The motion itself may have promoted the first lateralization of a function to the left brain, a spark that set in motion the development of language, tool use, and much more." No kidding!

Fox sums up that analysis with his own comment, "Now you've got a not-so-smart, mostly upright, well-fed primate with a killer fastball and reproductive advantage. Add a lump of chaw and you've got your average major-league pitcher!"

But that's baseball, and not all balls are thrown like a well-aimed rock that kills a wild boar, or batted with a stick into the outfield stands. The major focus of THE BALL is on huge spectator sports that involve a ball of some kind as the central focus (the "object" of the book's title) in active and often violent contention between opposing teams over some patch of territory. It's easy to imagine, as Fox posits, that such games evolved from hunting contests of competing tribes on the same territory.

Creation myths vs evolutionary processes

The stories that persist about the day and time and place a particular sport was invented are mostly myths. And as the baseball-loving evolutionary biologist Stephen Jay Gould has pointed out, most people, given the choice, will choose the creation myth over the real history every time. The truth is that evolutionary processes do not easily yield symbols for reverence, worship, or patriotism, and these elements are needed to feed the popular lust for heroes in sports which, for the most part, actually evolved slowly, over centuries, beginning invisibly and untraceably in prehistory.

Even though the "invention" of baseball is attributed to Abner Doubleday, fixed in time to the year 1839 and memorialized with a plaque on the mythic spot, in Cooperstown, New York, at the Baseball Hall of Fame, it has been well established that this information is hearsay generated from a single unreliable and thoroughly discredited source. The truth--without a doubt--is that American baseball evolved slowly from an old English children's game played by hitting a ball with a stick and racing to a "base" before being tagged.

A clear exception to the creation myth is basketball, undeniably an American game, named for the peach baskets nailed to the walls exactly ten feet above the floor at either end of a YMCA gym in Springfield, Massachusetts at the end of an assigned 12-day search for a game that could be played indoors in a gym, in limited space, in the winter-time. That was the assignment given in 1891 to one James Naismith, a 30-year-old theologian and gym instructor. Basketball is without doubt an American invention, but unlike American football and baseball, it has become an international sport, largely through the agency of its inventors in the worldwide YMCA.

|

| With basketball a favorite cold-season, indoor sport played around the world in the 21st century, it's hard to imagine that it was invented by a YMCA coach in just 12 days on order from his boss in Springfield, Massachusetts in 1891. |

Who would have guessed that only a century later, the game of basketball would be played by 200 million worldwide, defy the limits of race and gender, providing a fast track out of poverty (along with football) and into glamour and riches for countless sports heroes--many of them very big and strong, some more than seven feet tall--idols set on even higher pedestals who otherwise might today be flipping patties at Burger King?

When sport, religion, and politics merge in a single spectacle

When his son asked the seminal question, "Why do we play ball?" Fox immediately recalled his undergraduate work in Central American on the Mayan ruins where he helped to excavate well-preserved ball-courts banked with spectator seating on both sides. The astonishing prevalence of these ball courts throughout the Mayan empire as well as among the Aztecs clearly indicated that these courts occupied a very important position throughout pre-Columbian Central America. Wall carvings suggested that the penalty for losing the ball game--played by teams focused on putting a single ball through a hoop projecting from the wall in the midcourt--was quite severe. Heads were lost, presumably sacrificed to the gods.

There is evidence that the severed heads were themselves sometimes used as balls, which makes perfect sense, because they are somewhat malleable, and roundish in shape. Moreover, the heads with long hair enable a kind of sling-shot effect that increases velocity and distance--a characteristic put to use with the extension aids in modern sports like tennis and lacrosse.

But the Mayans didn't really need to use human heads as balls, because they discovered rubber as an ideal material for a ball, and by including in the recipe a local vine which made the polymers bind together in a process resembling vulcanization (not discovered until the 19th Century), their ball, large and heavy, was amazingly resilient and ideally suited for the ball game so immensely popular in prehistoric Central America.

|

| Ball courts throughout the Mayan world, like this one in Honduras, showcased teams of competing athletes 3,000 years before the first super bowl. Their game was the first recorded organized team sport in history, watched by thousands of spectators cheering their champions. Two teams of up to four players each would pass the large rubber ball around, without having it touch their hands, and try to make it pass through one of the elevated stone rings projecting from the sides of the court about the size of a basketball goal but turned 90 degrees. The glory of winning the difficult game was more than balanced by a potentially severe penalty for losing: beheading. |

There is abundant evidence that these ball games might have been used as a practical way of resolving disputes between neighboring city-states within the Mayan empire, providing an exciting, gladiatorial style of entertainment to the populace--which helps to justify lopping off the heads of the losers. If this kind of sacrifice pleased the gods sufficiently to ensure an abundant maize harvest, so much the better.

So the Mayans actually perfectly an ideal combination of religion, politics, and sport many centuries before European arrived to "civilize" the Americas. What might we learn from their example, in the 21st Century?

Choosing between sport and religion

|

| "Football" in most countries outside the USA is the game called soccer on the west side of the Atlantic. But the fans are indistinguishable. These Brazilian soccer fans celebrate by removing their clothes and painting their bodies. |

Of course I said that to annoy my mother, but the truth is that I actually believe that witnessing a sporting contest on Sunday morning is a healthier way to exorcise the demons, vent the passions, and refresh the spirits than listening to sermons, singing hymns, or speaking in tongues. In the words of John Fox, such sporting contests can be "irrational, violent, utterly pointless, and absolutely thrilling!"

In fact, stadium-style sports today can be likened to religious experience in the violence and passion of the spectators surrounding whatever contest is being played to control whatever ball is being used, and whatever goals or targets have been established to determine who wins and who loses. In the 21st Century, neither the winner nor the loser of the contest will suffer the consequences of a lost head. But to many athletes and their coaches, the bonuses paid for winning, or the failure of a contract renewal as a result of losing, can seem just as consequential.

Another book is needed, with a sharper focus

The Fox book, as noted, is entertaining and readable, especially when it concentrates its inquiry on the way the balls were constructed historically--sometimes very expensively and painstakingly, from materials we wouldn't think of using today: human and animal hair to stuff inside sewn circles of leather; inflated pig bladders; crushed cork, and the like; and especially when it details the in-person investigation of exotic sporting contests in remote regions of the world, all of them hangovers from the pre-industrial age.

|

| The modern form of tennis requires competing players or doubles teams to get the ball over the net on each stroke, without sending it out of the court. This photo shows the advantage of "covering" the full court in doubles with one player at the net and one on the back line. |

The next book could deal with the kind of ball games only made possible by the industrial revolution, calling for the direct interaction of "balls" with particular well-engineered standardized qualities, which stand in for the person--balls that are actually proxies for the players. These games include lawn bowling in all its forms, croquet in all its forms, and the entire family of billiards, pool, and snooker.

One of those games--croquet--actually belongs in a category all to itself; it's the only sport played in the out-of-doors that permits and actually encourages as a necessity for winning the player's "capture" and use the opponent to accomplish his own ends. So in a way, the violence in croquet is more cruel and deliberate than the furious action seen in grand stadia witnessed by thousands of screaming fans on opposing sides.

Our croquet literature is full of instances in which a hapless novice, eager to play, spends the entire duration of the croquet game--except for a few minutes--watching himself (as his proxy balls) be deliberately and cruelly (or so it seems) used by the opponent. Surely there is no more exquisitely terrible damage to be done an opponent than by such bloodlessly psychic violence, accentuated by the comparatively slow pace of the game!

|

| Only in this lawn sport can the balls of the opponent be "attacked" and moved around to the advantage of the opponent. But many other games--from chess to bocce to billiards to monopoly--also employ "proxy" elements with which the players are identified. Photo by Johnny Mitchell. |

Lawn sports were not developed until the Industrial Revolution also made possible the manufacture not only of standardized balls, but also efficient turf-clipping machines, so references to "early golf" or "prehistoric croquet" are fairly far-fetched. And even if such lawns existed in prehistory, what remains would there be to prove it?

So for the next book, no expensive international archeological junkets will be required to Central America or seaside British villages. Only by Googling "croquet" in his Boston office, Fox might have discovered a sport worth his investigating, if only for the unique position of croquet among all the other sports he tackles as the one in which the player most strongly identifies his ball as himself. He could do sufficient anthropological field work at Cheltenham in Britain or Palm Beach in the United States.

If Mr. Fox ever played monopoly, he would remember that he got a chance to choose to be the Top Hat or the Scottie Dog, for example. The piece he chose for himself really was a stand-in for his physical body on the monopoly board. Everything that happened to that Scottie Dog, usually as a consequence of the volatility of the marketplace or the bad luck of the draw, or his own over-confidence in developing a property too much, too soon, was deeply felt as a personal achievement....or failure.

Like basketball, croquet in its essential elements--despite all the murky and dubious accounts given for its "true origins"--was also created as a popular sport almost overnight, when John Jaques discovered a primitive form of it in Ireland, brought it back to England, put together a sensible set of rules, figured out what the equipment should be, and packaged it all into a fairly inexpensive set for sale to the general public. It caught on like wildfire, and soon became a highly regulated and rigorous sport, at the top level, now played throughout the world.

I believe croquet is disparaged--not just by Fox but in the media generally-- mostly because the easiest response to something you don't understand is to denigrate it. An adequate and compelling description of croquet has not yet been made to the general public, and perhaps can never be. In describing or explaining top-level croquet as it has evolved over the last 150 years, you would have to recommend the intense focus and drill of a Reg Bamford; the finely-honed risk-versus-gain calculations of a Chris Clarke; and the near-insane self-belief and confidence of a Mark McInerney. But how can you talk about these elements to someone who doesn't understand the game itself?

I'd like to see it attempted. But it's not going to be done by me, and it won't be done by Mr. Fox, unless he subjects himself to a radical change of focus, and is willing to content himself with a very small print run for "The Anthropology of Croquet."

In the meantime, consider the happy results of that portion of our species who have mastered mere survival sufficiently to adapt hunting, capturing and killing tools to other uses. Examine the goods in a modern sporting goods store, and you clearly see, squinting just a little, the primitive roots of most sports in the implements of ancient hunts: spears and clubs (and mallets), nets to catch an animal (or a ball?); stones (or balls) to throw; and most of all the balls themselves--the most animate of inanimate objects in our material world--and especially the balls on Mayan courts, made entirely of rubber; and 21st century croquet balls manufactured with an impressive degree of uniformity in rebound and circumference.

So far, you and your species have survived. Congratulations!

Shall we have a game of croquet now?

After earning a degree in archeology, John Fox went on to get a doctorate in anthropology, and now lives near Boston with his wife, two children, and a half-retriever. His new book, "THE BALL--Discovering the Object of the Game," is published by Harper Perennial and available from multiple sources on the internet from prices ranging from a few dollars to the original publisher's list price of $14.95.