|

Back to |

| The Front Page |

| News & Features |

|

Inventing the American game

|

|

by Bob Alman layout by Reuben Edwards Posted October 13, 2005

|

Herbert Bayard Swope, Jr. is a handsome man of imposing stature and bearing – qualities that served him well as a television producer in New York and Hollywood in the 50’s and 60’s. His beautifully modulated baritone was regularly heard over the airways in the 70’s and 80’s when he made a second career in South Florida as a radio and television personality. In the nineties he mostly contented himself with columns and occasional writings in the local Palm Beach press. Today, his image is perfect Hollywood casting for an elderly and accomplished man of means. Recently widowed, he is still in demand in the 21st Century for his funeral orations for Palm Beach friends he has outlived. Most significant for our purposes, however, was his presence at a critical juncture in the American game of croquet. The essential distinguishing features of today’s American Rules croquet were first popularized in the early 20’s largely through Swope’s father and his circle of friends and employees popularly known as the “Algonquin Round Table.”

The rambling Palm Beach house of Herbert Swope, Jr., cared for by a modest retinue of house and grounds staff as befits life on the enchanted island, is not of the grandest variety, though it has grand spaces inside, beautifully furnished with paintings and memorabilia in every room, souvenirs of a rich life spanning most of the last century. The house is of an era when neutral hallways were not built to connect various rooms. All the rooms follow on, from large to small, radiating outward from the large and high-ceilinged central salon that goes all the way through, with curtained windows overlooking the Intracoastal Waterway and the high-rises of downtown West Palm Beach in the distance. There are small, intimate rooms for tea, big bedrooms, and tiny alcoves serving as libraries and personal offices stuffed with mementos of a rich life well lived.

It’s a warm, friendly and welcoming house that feels your presence – the floors sometimes creak a bit, the china cabinet doors rattle as you pass, and you are surprised to come upon a big old 1920’s kitchen that, mercifully and miraculously, has not been modernized. And beyond, there’s the dining room, the only room with no pictures on the wall, but huge mirrors that reflect a dining table that could easily seat 18 – almost half as many as in the huge Victorian the Swopes occupied in Great Neck in the 20’s, a joyful space for conversation, real conversation, the way educated and worldly people conversed before there was television, and before even before there was radio, which only emerged in the late 20’s.

|

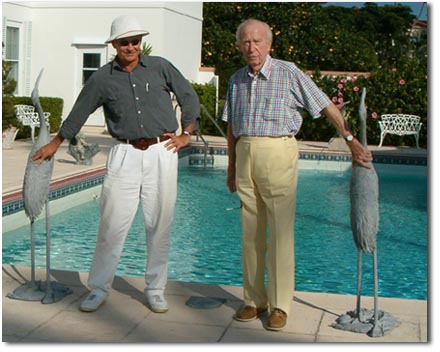

| Bob Alman and Herb Swope, Jr. by the Swope pool and lanai in Palm Beach. |

The “Junior” is well named, for he learned the lessons of life at his father’s knee. Herb Senior lived the life he wanted to live and made no distinction between work and play, between friends and co-workers, or even between night and day. It was a charmed life, an enlightened approach to life, and Herb Jr., grew up familiar with that style, to lead a charmed life of his own which came to rest in Palm Beach.

The crucible of the American game: Long Island’s North Shore in the 20’s

After the First World War, old-world values gave way to 20th century opulence in what is now called “The Gatsby Era”, a brief golden age of flowering American culture. Little about it looks typically American from today’s perspective, but in that time the American empire was in full flow, and its capitol - of art and culture, finance, publishing, innovation, wealth – was without a doubt New York. For the glitterati, that meant Manhattan on the weekdays and someplace on Long Island on the long weekends – perhaps Great Neck on the North Shore, just across the sound.

Such was the euphoria of the 20’s that Americans imagined themselves capable of anything, any achievement, any self-invention – and entirely outside the regular ebbs and flows of history. It was an illusion to be irrecoverably shattered in the crash of ’29 and all but forgotten in the long grind of the 30’s towards a second world war.

For those who survived it and survive it still, the “Roaring Twenties” are little more than a dream dimly remembered – unless you happen to be talking to Herbert Swope, Jr. And then this fabulous era becomes real, personal, and magical in his telling. It was at Herb’s father’s place in Great Neck (and later Sands Point) that everything uniquely memorable about the twenties came together in one place and in one point of time. Herbert’s father, Herbert Bayard Swope, Sr, had made a name for himself early in life as a writer by penning the Pulitzer Prize winning Inside the German Empire in 1917 while still a young man and a correspondent for the New York World.

The elder Swope came back to America to help usher in a new era in newspaper publishing, first as City Editor of the New York World, and later as it’s first Executive Editor. Among his innovations that shaped the practice of journalism as we know it today were the op-ed page and the position of “executive editor” itself – the person who makes things happen at the highest level, who makes essential connections, who maintains the vision and keeps the energy going forward.

But what Herb Senior is best remembered for is the stable of now-legendary writers and editors who worked for him or with him, many of whom came into their own with his support and encouragement – people like Dorothy Parker, Maxwell Anderson, and Alexander Woollcott. They are among the legendary figures who came to be known collectively as the “Algonquin Circle,” because they regularly had lunch during the week at the Algonquin Hotel in midtown Manhattan. The elder Swope seldom attended the lunch gatherings – he was far too busy for that.

On the weekends, however – and nearly every weekend – many of this circle were regulars at Swope’s weekend house, not just for a dinner or an overnight, but for a long weekend, a three-day party that embraced dining, talk about everything moving the American culture, drinking and gambling and carousing, and…croquet. Yes, croquet all afternoon sometimes, and into the night, on the great lawn sloping down to the bay, circled with cars, headlights beaming to allow play to continue until the game was over. The closest neighbors were the Ring Lardner family and Scott and Zelda Fitzgerald and – for a while, Clifton Webb. Herb Jr. remembers those days and nights vividly – especially the croquet – and the stories needs to be told in his own words.

Croquet without boundaries

|

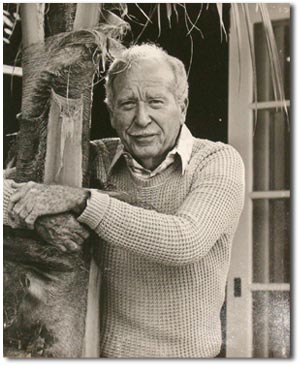

| This is one of Swope’s favorite photos from his Hollywood years, where he directed television and played croquet with the likes of Harpo Marx, George Sanders, Louis Jourdan, and Daryl Zanuck. |

And did they have good equipment in those days?

“Not really. We started out at the Great Neck house with rubber-tipped mallets in 1922 – and that was advanced for that time, better than the plain wooden ones. And then shortly after that, Jaques of London sent over some of their sets, with better equipment. And we started using that Jaques equipment, and that caused us, in a way, to take some of the roughness out of the game. With the better equipment, and the narrow wickets, we became better at the game.”

But you still played without set boundaries.

“Yes, always.”

Herbert Swope, Jr. was a child when the weekend croquet became well established in the mid 20’s. He learned the game it by watching, in the course of running errands and doing whatever else a 10-year-old boy from a well-to-do family did in the 20’s, and was eventually invited to play with the adults. By the time he was 12 and 13, he played a respectable game of golf, but his father still kept him around on the weekends, because he was also becoming a good croquet player – one of the best in the group.

The period 1922-26 at the Swope place in Great Neck established and somewhat popularized a rather sophisticated 9-wicket game of that time among a certain class of people – we might call them, perhaps, the glitterati of that time, encompassing writers, actors, journalists, statesmen, amusing dilettantes and wannabe’s, and everyone else who moved in the swirling orbit of one of the most celebrated newspapermen of the century – Herbert Bayard Swope, Sr.

The house at Great Neck was a huge Victorian on the top of a hill, three stories, with towers and turrets and gables, and a wrap-around porch, surrounded by great, ancient pine trees. A previous occupant of the house was Lottie Parker, who wrote Way Down East, one of the blockbuster novels of the early 20th Century. Great Neck was at this time what the Hamptons were later to become – the place to escape Manhattan on the weekends.

“These parties were peopled by my father’s friends,” says Swope, “and many of them worked for him. Woollcott was on the New York World, Laurance Stallings, Franklin P. Adams and Lon Stalling were on the World, Walter Lippman…. I could go on. It was a great newspaper. He had some of the most famous writers in America on his staff. He had Quinn Martin doing the movies, with Woollcott and John Baldison, the playwright, doing theatre reviews."

This was the Algonquin group. Not all of them played croquet regularly, but most of them played at least occasionally. Swope remembers especially the croquet of Franklin Adams, Deems Taylor, George and Beatrice Kaufman, Marc Connelly, Robert Benchley, Harold Ross, Art Samuels, Robert Sherwood, Herman J. Mankiewicz, Jane Grant, Ruth Hale – and most especially, Dorothy Parker.

But how did it all get started?

“My father had gone over to the war in 1917 for the World as a reporter. Then after the war he stayed on for two years, when he was writing Inside the German Empire. He witnessed the Versailles Conference, and Lord Beaverbrook invited him to stay on and become the publisher of a British newspaper. After much brooding, he decided not to. It was in England that he saw croquet played, and perhaps that’s what gave him the idea of playing croquet at Great Neck when he came back to us from England in 1922.”

But, curiously, the senior Swope did not bring back the rules to the “Association” game, which were well established by then in England. So where did the croquet game that Swope played with his friends at Great Neck really come from? And how was the innovation of “carry-over deadness” introduced?

Sadly, Herb, Jr. can shed no light on this particular point. “I have no idea. It was the game they always played. No boundaries. Carry-over deadness.”

But on one point there is no doubt: In 1922, at Great Neck, they played croquet with carry-over deadness every weekend - and this is an important and exciting assertion if you know anything about croquet history. Because according to the best research available, confirmed by David Drazin, the English historian of the sport, the earliest known printing of any rules in the world incorporating deadness carrying over from one turn to another was in an obscure publication seldom cited in croquet histories, whose exaxt publication date is not known. (It could have been published at any time between 1890 and 1910.) It was not until the mid 30's that carry-over deadness was seen in an influential rulebook, for Kentucky Croquet.

| “CROQUET IS NOT FOR SISSIES” |

| Alexander Woollcott wrote to a friend an account of a remarkable tour de force in 1933 at the Swope place at Sands Point. The letter proves that the intensity of the croquet among Swope’s circle lasted well into the ‘30’s, although of the original group, affected by the Depression gripping the country, had gone west to work in Hollywood. “I suppose you want to hear the latest Swope story,” Woollcott wrote. “Burdened with Gerald Brooks as a croquet partner, he became so violent that Brooks agreed to do only what he was told and thereafter became a mute automaton, a condition which Swope enjoyed hugely. Brooks never moved his mallet or approached a ball without being told by Swope: ‘Now, Brooksy, you go through this wicket. That’s fine. Now you shoot down to position. Perfect!’ and so on. Finally, before an enthralled audience, Swope said, ‘Now you hit that ball up there on the road. That’s right. Now you put your little foot on your ball and drive the other buckety-buckety off into the orchard. Perfect!’ It was only then, from the shrieks of the on-lookers, that Swope discovered it was his own ball which had been driven off.”

Woollcott’s own excessive behavior on the croquet lawn has been reported by many, including mystery writer Rex Stout, who played croquet in 1937 at Woollcott’s place in Vermont. “When I roqueted Woollcott’s ball into a blackberry bush,” Stout wrote, “he picked up my ball and hurled it at my head from ten feet. Croquet is not for sissies.” |

The weekend parties were not merely a function of the elder Swope's work. They were pure pleasure for a man who made little separation between work and play, who played and worked very hard and with tremendous gusto, who hired his friends and enjoyed and respected the people he worked with. I had many more questions for Herb, Jr., about the people who revolved around Herb Senior's New York World. I asked, for example:

According to a biography I recently read, Scott and Zelda Fitzgerald moved to Great Neck near the Swopes in 1922 in the expectation that Scott’s play The Vegetables would be a great comedy hit on Broadway. But it turned out to be a flop. The couple maintained their residence there until early 1924, and according to the biography, it was a down period for the celebrated novelist, when he did a lot of drinking and partying. Did you see any of this behavior?

“Yes, he did a lot of the drinking and partying at our place.”

Biographers say this was the gestation period for “The Great Gatsby.” Were those parties, do you think, an inspiration for the characters and content of that book?

“I can’t say, but the feel of the place and the parties is in that book. We would have maybe 40 people during the day, 25 or 30 people would be there for dinner, with rather formal cocktail service and so on, but in a very relaxed atmosphere, all full of joy and gaiety. And at that time, at Great Neck, the house was at the top of a hill, and we started playing croquet at night. You drove up from East Shore Road, and there was a partially wooded croquet area next to the house. And we had the cars parked all the way down the hill with the headlights on, and they played by that light. It was very, very dramatic. I say “they”, because I couldn’t stay up that late, I would have to go to bed – until I became so offensive they finally had to let me stay up and play, too. And we played under the pine trees…the great thing would be to drive a ball up into the crotch of a pine tree, so you’d have a hell of time shooting it out. There was no ‘baby’ stuff at that time, no lifting the ball out, you played your ball where it lay, too bad if you had no backswing.”

|

| Swope (holding the ball and with his back to the camera) plays Malletball with family and friends on his commodious lawn. “It’s very much in the spirit of the wide-open games we played at Great Neck in the ‘20s,” he commented. |

It almost sounds like Extreme Croquet…and a little like the new Extreme Malletball, too, that we played the other day on your lawn.

“Yes, that’s very much in the spirit of what we were doing, the wide-open informality of it. And they would play all day long and far into the night.

“But I was talking before about the characters from Gatbsy, many of which sprang full-blown from Scott’s head, primarily, of course, newspapermen and theatrical people. People like Heywood Broun and George F. Kaufmann. Harpo Marx was a very good player. Two guests for the weekend were Herbert Marshall and his wife Edna Best, the famous English actress.

“And then you had wild things that would happen. More than once, on Monday mornings, when the staff were going out to clean up things, they would find Scott Fitzgerald asleep on the lawn. They’d wake him up and send him home.”

So he came to the parties? Did he bring Zelda?

“He did, indeed. They lived only a few houses away, in 1922.

You remember Zelda Fitzgerald?

“I do, very well. Once she took off all her clothes and chased my uncle Bruce, who was only 16 at the time, up three flights of stairs, and he ran from her, he actually escaped. And we all said later, of course, ‘What a fool you were!’ This beautiful woman chasing him eagerly, and he runs upstairs and locks himself in. My mother’s room was on the third floor, and she kind of got a robe around Zelda and took her home.”

Should I include this story…?

“I think you probably can, it’s pretty mild. I mean, nothing happened!”

Did the Fitzgeralds ever play croquet?

“I don’t remember. If Scott did play, he wasn’t any good. There was a lot of talking, you can imagine.”

“I don’t remember. If Scott did play, he wasn’t any good. There was a lot of talking, you can imagine.”

As an 8-year old, Herb, Jr. wasn’t that interested in all the talk that went on. He liked the games very much, he ran errands, and he had his favorites among the regular guests – especially Dorothy Parker, who was always very sweet to him personally, but who could cut someone dead with her acerbic wit.

Was it only at your family’s house in Great Neck that you played croquet?

“Oh no, by the mid-twenties, croquet was played on many of the big estates on Long Island, and at the clubs. We played in Great Neck for only four or five years, before we moved to another house at Sands Point.”

Were the people mostly the “Algonquin Circle”?

“Yes, totally – the people my father worked with or hired when he came back as City Editor on the New York World. They came for the entire weekend, to gamble and play croquet, and as I said, they drank a lot.”

But you remember clearly the game you all played then, a four-ball game, with strict sequence, and carry-over deadness? You’re sure your father didn’t bring back the English rules, which were very well developed by then?

“No, he and his group really developed their own rules on Long Island with the group, with Woollcott, Heywood Braun, Dorothy Parker, and the rest.”

Who played the best croquet?

“Dorothy played modest croquet, not great. The best players were my old man, Jack Barrymore, Alexander Swartz, a friend of my father, Woollcott…”

Did they play singles or doubles?

“Both, but mostly with partners. They switched around, no permanent partners. They tried to balance the strengths of the partnerships. And there was a great deal of betting. They used to do doubling in croquet, as you do in backgammon. Ten dollars to start, then I’d double you to $20, then later you’d double me for $40…”

I play backgammon, and doubling in croquet sounds kind of crazy. In backgammon you double when you have a clear advantage, but your fortunes may turn at any moment, because there’s a stronger element of luck in backgammon than in croquet.

“It’s the same in croquet. Somebody takes the double because they think they’re going to get a good run in the next turn… I know I played in one game with the writer Arthur Summers Roach and myself, against Pop and somebody else. But the doubles got up so high the bet was $640, and we all stopped doubling at that point. Nervousness was setting in. And then there was a famous game that’s already been written about, a four-way game between Woollcott and Swartz and the artist Neysa McMein and my father. They were playing a two-out-of-three match, for $1,000. They each won the first games, and then they never played the third and final game of the match. Never finished.

In those days, a thousand dollars was a fair piece of change.

“Yes. The weekends – every weekend – were big, noisy, bright, funny, and jammed. Forty people, sometimes. Sometimes crazy things happened, kind of got out of hand – like the betting.

But it must have been boring for you sometimes, as a kid with all those adults…

"It was, sometimes, but there were funny things that happened. My mother would use me as the messenger at two and three in the morning, when there were these terrible thunderstorms among those enormous pines, 200 feet tall. We had terrible storms, really giant ones, and my mother would send me around to all the guests and have them get up and go down and join Mrs. Swope in the library until the storm passed. They had to get up and go down. Orders. So I remember one door I knocked on was Herbert Marshall, the great actor, with a wooden leg, who was married to Edna Best, the wonderful English actress…"

I never knew Herbert Marshall had a wooden leg…?

“He concealed it beautifully. So I knocked on his door and asked him to join us in the library, as instructed, and he answered, ‘All right, old boy, in a moment.’ I went downstairs and reported, but after a while when he didn’t come down, mother said, ‘Where’s Marshall?’ She had me go back up again: ‘Mr. Marshall, Mr. Marshall! Mrs. Swope is waiting for you in the library, and the other guests are there. Are you coming down?’ There was a pause, and then he said, ‘I will, old boy, as soon as I find m’ leg.’ Which had rolled under the bed.”

You’re lucky he didn’t ask you to fetch it for him.

“So many stories like that, it gets away from croquet, but that was part of those incredible days at Great Neck until ’24 and ’25, and then we moved to Sands Point, where we continued the game at the big house there, and that’s where eventually the more serious yearly tournaments began, with Averill Harriman and Ogden Phipps, and…

But the rules of the game didn’t change…

“No, we still were playing the 9-wicket game, with four people, a two-sided game, always with four balls.”

So now you’re at Sands Point, playing carry-over deadness, no deadness boards, and no wicket clips…

“We did have wicket clips, but we rather pompously didn’t use them, we didn’t think we needed them, and we didn’t have a deadness board either. We remembered deadness.”

Yes, Teddy Prentis has told me this, also, that he thinks he remembers the first deadness board, in the late 50’s. But that’s crazy-making, it’s bad enough not to have wicket clips, but not to keep deadness…

“It would cause any number of fights, needless to say: ‘What do you mean I didn’t score that wicket, of course I did, goddamn it!’”

Playing a game without those aids at any club in American today would be considered nuts, absolutely nuts…

“We would have thought that was lazy, unworthy, having to depend on those memory aids. And the passionate disputes were somehow part of it all. Once Woollcott and my father had a terrible fight on the first morning of the weekend, and Woollcott stamped off the lawn and took a train back to New York These things happened frequently. Most of these disputes were eventually smoothed over and forgotten.”

Did I hear you say there would be 30 people for the weekend?

"At dinners, there would always be 20 or 30 people."

Just as a regular, normal every-weekend occurrence?

"Yes, lots of ‘regulars’, they all just showed up, they didn’t have to be specifically invited."

A privileged and definitely golden circle…

“Very much so. And that Algonquin group lasted in New York, I suppose, into the early ‘30s…

The Great Depression, though, changed everything and moved a lot of people around…

“This was a rather close-knit circle of friendships, and some would drop out of course, and others would come in, and these were people in their twenties and thirties, remember, and success would come to them at that age very quickly, and then they’d move on in life. Maxwell Anderson’s play “What Price Glory” was a great smash, for example, and all these people on the paper who were reporters were also writing these great hits on the side - plays, books, motion pictures. In Hollywood, there were a lot of people playing croquet, too, but it wasn’t the same.”

Less quality?

“For a while, yes. Louis Jourdan was great. He had a habit, even in the nine-wicket game, which was infuriating, up at Goldwyn’s. He’d start right in front of the wicket, and he’d light a cigarette in that elegant Jordanian way, and put it down, then he’d play, and that son-of-a-bitch would run two wickets and get two extra strokes and pick up some other balls, and he could run the whole course and get back in time, hopefully, to pick up the stub of the cigarette he’d left burning. That was a triumph, for him.”

But wait a minute, Louis Jourdan had to be much later, not in the 20’s or even the 30’s. Let’s back up a bit: So there was the crash of ’29 and the beginning of the Great Depression and times get harder for most people, but movies were big, paying big bucks to writers, so you started to see some of your group move to Hollywood in the 30’s…

“Yes, it started in the late 20’s and early 30’s. Sam Goldwyn would bring out to Hollywood one famous writer, then it started, more and more went out. So the Algonquin group started to play croquet out west and that scene gradually shifted to Hollywood.”

| HAVE WE FOUND THE “MISSING LINK” IN THE ANCESTRY OF THE AMERICAN GAME? |

| American croquet owes a substantial debt not only to the Herb Swopes and their friends, but also to Dr. David Drazin of England, who first pointed out a long-standing fallacy in the assumption that the American Rules game descended from an antique form of English croquet. His research has shown that the main distinguishing feature of the American game – carry-over deadness – was probably an American invention and certainly never a codified part of the croquet mainstream in England at any stage in its development. If the main value of this article is to pinpoint the origins of deadness in the American Rules game, that job may well be incomplete. It could be that we have missed a link somewhere. In this article, we have declared that the earliest regular play of carry-over deadness anywhere in the world which can be reliably verified by persons still living was at the Swope place on Long Island, beginning in the early twenties. We welcome any evidence to the contrary. Let us know by email to the editor of Croquet World Online Magazine: BobAlman@aol.com.

Upcoming soon in Croquet World Online is a scholarly article by Dr. David Drazin, croquet historian and bibliographer, tracing the origins of carry-over deadness in American Rules. (Click here to see Croquet World Online’s abridged version of Drazin’s croquet bibliography.) |

“Yes, by the end of the ‘30s I suppose you could say that the main action had moved west. Sam Goldwyn, Prince Romanoff, Moss Hart, Harpo Marx, all from New York, Daryl Zanuck loved it, and both the Hawkes brothers, Howard the director and Bill the producer. And then later, by the 40’s Louis Jordan, Tyrone Power, George Sanders. The Hollywood croquet scene peaked in the 40’s.”

Did you have occasion to play out there in this period?

“Not until 1955. I went from CBS where I was directing in New York to Hollywood, 20th Century Fox.”

Okay, so let’s talk about the equipment you’re using now, it must have improved over the years.

“Oh yes, we had the iron wickets, with spikes.”

Fairly narrow, but loose by today’s standards in the USCA.

“I suppose so.”

I talked with the late Tom McDonnell about this many times when I lived in San Francisco. He started croquet in Northern California, and he said that when the Goldwyn court was lost, he found playing space somewhere else in Beverly Hills – I think it was Coldwater Canyon Park – and that was in the early 60’s.

“Yes, I’ll tell you what happened. Things started to fall apart in the sixties, and that’s when I left Hollywood. Other people had left, gone to the theatre, another studio, died, whatever, and gradually the game was disappearing, and people were moving and dying off, and they weren’t being replaced. Which is a problem you could have here in Palm Beach if you’re not careful…”

Yes, there’s an aging demographic.

“A lot of the players you have in the USCA are carry-overs from the Osborn era. You know, I was in that group who got croquet into Central Park.”

Yes, we’ve got to get into the Osborn era now, I think we’ve ended the first chapter.

“Osborn’s fame began in West Hampton, and he and I played with two Brits. This was in the 60’s. John Solomon was one of them, and we had a great match on this rough-hewn lawn down in West Hampton. Jack and I were partners there at the West Hampton Mallet Club.”

Was that club playing nine-wicket croquet?

“Yes, still nine when I got there.”

But surely John Solomon persuaded you to play on a proper English 6-wicket court. They had officially adopted the 6-wicket setting in 1922.

“Yes, that’s right. He was awfully good, polite, beautiful player, unpretentious. And Nigel Aspinal, who came over later, is a great player.”

He hardly ever plays now, though.

“Really?”

I have been told that he got the worst case of “wicketitis” ever in the history of croquet, couldn’t go through any wicket, no matter how close. So he just stopped playing, stopped cold. An English friend told me that just in the last few years he has begun to play occasionally, a casual game now and then, but no serious competition. But tell me about the first time you saw Osborn.

“The first time we had any contact, he called me, wanted me to come to West Hampton for the weekend to play in this match with the British - Solomon, and a well known but secondary player. It was a wonderful match. Teddy Prentis was one of the ball boys, picking up cigarette butts. And it really was a delightful day, and the British were splendid about it, looking rather suspiciously at us, wondering if we knew anything about the game at all.”

And they were playing your rules?

“Yes, and Jack and I became friends, and that’s when we started to found the club in the city, and I got permission from the commissioners of parks, who built two courts for us, and the first one they had put massive club woods around it, and it just didn’t work, and we said, we can’t have that! So they said, ‘Well, we’ll give you another court in the park,’ and that’s when we moved to the bowling greens. The first courts were right by the pond at 72nd Street, a beautiful course, which we could never use, because it was surrounded by great firs for fences all the way, it didn’t work for the game, getting there, parking….and it couldn’t be protected either, it was too isolated. So there was a fight with the bowlers, at first.”

Yes, I know about the bowlers. They’re even more territorial than the golfers!

“But finally we made an agreement to split the facility, and it worked fine, we had many tournaments there, nationals included. I liked Jack Osborn a great deal, in spite of everything, and we built up an organization together, we were great friends.”

Do you have any insight into why Jack Osborn did what he did? He gave himself completely to the game, he was a croquet monk, everything in his life was pointed towards building a national organization and getting courts built and having tournaments. He was a very clever guy, with a sound background in marketing and communications, so surely he didn’t think he was going to get rich on croquet, did he? He was always living hand-to-mouth, he scraped together money somehow when he needed it, for himself or for the USCA, he worked hard, a lot of the time it looked like it would never work and finally he drove himself out of the management structure of the USCA with that intense drive and marketing expertise they didn’t understand and the opinionation that came with it…

“It was a curious drive that he had, he was married to a very wealthy actress, he lived in a beautiful house on 71st Street off Madison, and he produced plays…. and suddenly all that life fell through, and he was in a one-room office, and as you say, getting nothing out of it, no salary…”

But I have heard a theory about Jack Osborn that has the ring of truth. It is simply that he loved New York café society more than anything. And that love fit very nicely with his notion of marketing croquet for the affluent class, and he would get to do what he wanted to do and be where he wanted to be with the people he wanted to be with. It’s just that he didn’t make any money…

“That’s a very good explanation. Jack had a wonderful job, and I was devoted to him, and he was a close friend of mine, a difficult man, but we hit it off beautifully. I would take my vacation from the station – the television station where I was producing at the time – and we’d work on Hall of Fame nominees, and I’d call from California and dictate nominees, and he’d take it down by dictation. And we won a tournament together. He was better than I was, but we were well matched. We got to the end, and so help me god, we were winning this big championship, and they had staked Jack out, and I had one shot to win the game by staking out myself – because I was a rover – and it was a pressure shot, maybe a 15 or 20-foot shot. So I bent over and took some swings and was very concentrated, and took some more swings, and suddenly I heard this voice saying loudly from the sidelines, ‘For the love of god, hit the ball, will ‘ya?’ And it was Jack. So I swung at the ball and it hit the stake and we won. Terribly exciting.

“I loved Jack. He was his own worst enemy in many ways, he offended many people, the West Coast people….well, you know that story.

Yes, I’m from the West Coast, I was very involved in croquet at the time, the San Francisco Croquet Club was a big deal by then, and Mike Orgill and I wrote about “the big split” in the second issue of our short-lived Croquet Magazine. This was in 1987.

“They must have hated him out there.”

Well, more like love/hate. We all knew that he had created the sport we loved, and we admired and respected him for that. But from a western point of view, it looked like he came close to wrecking the entire structure of the USCA. At the time, I was the president of the San Francisco Croquet Club, and I remember well the vote our board took – whether to stay in the USCA or withdraw, as so many other Western clubs did, and join the ACA [American Croquet Association] revolt, Stan Patmor’s organization out of Phoenix. I voted with the majority of the board, and we stayed in the USCA by the slim margin of 4-3. My viewpoint and the viewpoint of our board was that this storm would pass, we already had a brilliant public club going, we were producing national champions, we had a great annual Open, one of the best in the country, every regular member of our club was a member of the USCA – and so we said that if we kept doing the right things, eventually the USCA and Jack Osborn would notice that.

“Good for you!”

I think I understand his marketing strategy. He was not interested in public clubs early on, he wanted the social elite, and he wanted the USCA to have that image. And he did that thoroughly. We knew that we were called “the San Francisco roughnecks” by some of the Palm Beach crowd, and we thought that was kind of funny, we weren’t really offended by it. But maybe the lingering public perception of that sustained effort that he directed so well to make croquet “elite” has become a curse, I don’t know. A friend and patron of mine from that era has pointed out something very interesting. That is, that Jack was a friend of yours and a friend of other New York people in café society who really were the east coast social elite, and it wasn’t just a piece of marketing hype. But the irony is that as soon as these people – including yourself – helped him get the USCA started, the USCA itself was a democratizing influence, instantly. All of a sudden, you had people who were not in the social elite…you had people who weren’t even wealthy! You had social wannabe’s, too. And for whatever reason, many of the elite retreated back into their private estates and country clubs, while the image of croquet as an elite sport remained as a sort of a curse. Because at the same time, Osborn was getting lots of press that said croquet was the “fastest growing sport in America,” but at the same time it was marketed as a sport for the elite. The image was schizoid, and it still is.

“Yes, that’s exactly what happened. Even after the Hollywood group split off in the ‘30s and ‘40s, East Coast croquet continued as a very elite, very personal, very private pursuit of the few, not the many. Averell Harriman, Ogden Phipps, people like that, it became enormously chic to play in these weekend tournaments.

“Pop was probably the main force in establishing this kind of croquet, because of the force of his personality, and because he loved the game, and so many people played it here and learned it here, and took it up. Like the Morgan group over in Westbury. Very chic, and they had their own little group over there. And these groups were somewhat aware of each other, but it was always very private and elite, not ever saying, ‘Oh, let’s have the public come on in,’ none of that.

“Then there was the ‘croquet disapora’ around the beginning of the depression, when so many of the New York people moved to California to work in Hollywood. Moss Hart among others, and Daryl Zanuck took it up, and it became a big California thing in the 40’s and 50’s, still very private and elite.”

And all this time, they were playing the same game, this wide-open nine-wicket game without boundaries and with carry-over deadness?

“Yes. The same game. But croquet was still going on around New York, and that’s when I became friends with Jack Osborn, in the 50’s. I had been in the war, in the Navy, for four years, and I was a television producer in New York, and Jack asked me to come down to West Hampton, where he lived, and play a match against the John Solomon and the British, and we played against them, and they beat us, and this little match was well publicized. And Jack and I started talking about a place to play. And eventually I prevailed upon the park commissioners to use part of the lawn bowlers area in Central Park. Which was the beginning of the New York Croquet Club.

Which brings us full circle. The New York Club in Central Park is really the beginning of public court croquet, and that club was the cornerstone of the fledgling USCA when it was founded in 1977. So I think we’ve completed Chapter Two. Thank you very much, Mr. Swope, it’s been a pleasure and an education.

“And my pleasure as well.”