|

Back to |

| The Front Page |

| News & Features |

|

More than one way to mark a mallet |

||||

|

by Ken Shipley Posted May 31, 2013

|

||||

|

||||

I hope someday my game will catch up with my mallet. If it could talk, my mallet would be saying, "Come on, dummy, I can make this shot in my sleep, what's the matter with you? Just hit straight for a change and this seven yarder will be a piece of cake...... Oh no, you missed again!" Or words to that effect. It's a drag having to play with a cheeky mallet.

I built my own mallets for a number of years and, before anyone comments, let me hasten to admit that the results were mixed. Some of my creations looked rather strange, some broke or came apart, some were too heavy overall, and some had shafts that were too weighty compared to the head. The first heads were 9", later ones 11", my current one is 12". A lot of experimenting.

|

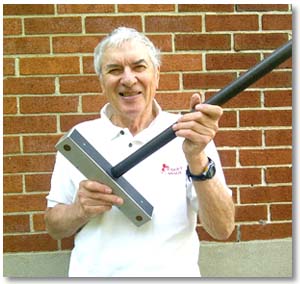

| Shipley shows off his dotty mallet here, and will tell you how the dots got there:: "I drilled little holes in the aluminum which made concave spaces into which I poured blue resin. If people don't want to go that trouble, they can experiment with dots from the stationary store." |

When mallet makers began adding peripheral weight to their mallet heads, I installed a lead-filled length of 1/2" copper pipe near each end of the head. This added 0.477 lb to the mallet, about 0.24 lb to each end of the head. The lead weights produced the desired peripheral weighting, and had an unexpected additional benefit. Before the lead-filled tubes were installed, the mallet made an annoying pinging sound when striking a ball. The sound deadening capability of lead virtually eliminated the ping. The photo below shows the latest version of the mallet.

|

| The latest version of Ken Shipley's mallet includes the addition of peripheral weights of lead on each end of the mallet head, bringing the weight to a little over three pounds. |

Dots are positioned to engineer specific shots

But there are also dots to facilitate cut rushes, on the top of the mallet head set back from the striking surface exactly half the diameter of a ball (1 13/16"). Diagram 1 shows how the dots are positioned.

|

Diagram 2 shows how, when the mallet head is pointed in the rush direction, the dot closest to the rushee helps determine the striking direction. Note: the mallet head should be close to, but not touching the rushee to avoid a possible fault. If I had (mis)spent my youth in a pool hall, I'd be able to eyeball these angles and wouldn't need these dots, but I didn't, so I do. Note also: there is a pull effect on the rushee in cut rushes which I do not attempt to show in this diagram.

|

These dots can also help with angled hoop shots, where, in order to run the hoop, the striker ball must miss the near stanchion (see Diagram 3).

|

Another set of dots aids peels

Diagram 4 below illustrates how the peeling dots are used.

|

These aids take advantage of the fact that the mallet shaft is dead straight, with no grips or indentations. The dots are positioned so that the inside of each dot is lined up exactly with the corresponding edge of the shaft. The procedure for a stop shot peel (no pull allowance) is then as follows, after the striker roquets the peelee and is ball-in-hand:

* Lay the mallet down with its head against the near stanchion, and shaft close to (but not touching) the peelee. Allow about 1/8 clearance past the stanchion.

* Position the striker ball in contact with peelee and lined up exactly the same as the peelee with respect to the shaft .

* Stop shot the peelee through the hoop (See Diagram 5).

|

This procedure avoids having to grovel about on the ground to sight along the sides of the balls to line up the peel. This works very well when the peelee is less than the length of the mallet away from the hoop. It also works well if the peelee is as much as 12 or 18" farther away. This involves positioning the mallet and pulling it back beside the peelee, and then placing the striker ball as described above. (If the peelee is farther away than that, I'm afraid it's back to groveling about on the ground to line things up.)

The more common peeling situation (in Association Croquet) involves the use of an escape ball, in which the peel is attempted, usually employing a roll shot croquet stroke, with the striking direction angled to the right, sending the striker ball to a desired position behind the escape ball. This will pull the peelee markedly in the direction traveled by the striker ball. The mallet and balls must be positioned accordingly (See Diagram 6).

|

All this will seem a lot of fuss and bother to those who do numerous triple peels and have their technique down pat (let's not even mention sextuple peels!). On the other hand, it will seem academic to those who have never tried a triple peel and don't ever expect to. I dream about being part of the first group, but in fact am closer to the second. I often think about trying a triple in a tournament game, but usually have so much trouble keeping a break going that a triple quickly becomes too risky. So, I mostly get to do it only during practice, when there's nobody around to watch. Also, this cheeky mallet of mine is always yammering at me about missing the last short roquet!. My only consolation is that my mallet is even dottier than I am.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR: When Ken Shipley discovered croquet quite late in life, he began playing in tournaments across Canada and USA, initially American 6-Wicket Croquet, then concentrating more on Association Croquet with occasional forays into Golf Croquet. Ken is a long-time member of the board of Croquet Canada, having been President, Editor of the Mallet (Canada's croquet newsletter), and now Secretary. For a number of years, he was also coordinator of CroqCan, Canada's annual croquet championship tournament. Ken has built a number of mallets. Soon after building the "apeeling" mallet, while playing in C Flight in the first "Croquet the English Way" tournament at the National Croquet Center in West Palm Beach in 2001, Ken won a game +26TP using the peeling techniques described in the article. He thought he was on his way to becoming a much more successful player. Unfortunately, so far that has been his only triple peel in competition, proving that the mallet can do it, but that Ken (the player) is the weak link in the partnership--a point his cheeky mallet is quite prepared to make with monotonous regularity. In spite of the constant stream of abuse coming from his mallet, Ken loves playing croquet at both club and tournament levels, for the competition and for seeing his many croquet friends.