|

Back to |

| The Front Page |

| News & Features |

|

The Shaftmaster of Connecticut explains the striking designs that spring from a love of wood |

||||||

|

by Gordon Kyle photos courtesy of the Norwich Croquet Company

|

||||||

|

||||||

Most mallet makers come to the task as croquet players. Gordon Kyle started, instead, with a small, successful and well established company with a stable of artisans expert in working with wood--for making cabinets, counter tops, and furnishings for people who love to live with real wood. Before he made a single mallet, he studied the playing characteristics needed to make the one instrument in the game the player can choose on his own to master the game. He's learned a lot in the last seven years and continues to innovate, with eight mallet designs in his current working inventory and many more in various stages of testing and development. This is the story, told in his own words, of how he has brought the passion, drive and expertise that distinguishes his wood products into the realm of croquet.

Disclaimer: This article is written from the viewpoint of a forensic, industrial engineer–NOT a "croquet savant"!

Norwich Croquet Company found its way into the hallowed halls of croquet mallet design through the back door. I knew nothing about the sport until I began to delve into the connection of Norwich, Connecticut, with the beginnings of backyard croquet in America. I had a notion that I might revive the fine art of all-wood mallet-making. Could an all-wood mallet perform as well as the top of the line composite head / graphite shaft mallets?

|

| Gordon Kyle invites players to try out some of his Norwich Croquet mallets at the National Croquet Center last fall. |

The first thing I learned was that 90% of a player's success on the court is the player and 10% is the mallet. The second thing I learned was about "peripheral weighting" and "mallet balance". The objective of these metrics combined is to concentrate as much weight as possible at the ends of the mallet head to improve swing accuracy, while eliminating as much weight as possible from the shaft / grip, with a total mallet weight of around 3 pounds. That's the weight required to create sufficient inertia when striking two one-pound balls--in the croquet shot--to drive them the desired distance.

Thus, the mallet becomes a three-pound pendulum. Compare our mallet pendulum to a tall clock pendulum. The obvious difference is in the "head" or weight geometry. The shaft geometry is different also. Both the clock and mallet pendulums are designed to maximize swing accuracy, but the difference is that the only resistance the clock pendulum encounters is gravity and aerodynamic turbulence. That's why both the weight and shaft need to be thinned down along the axis of the swing.

Wood mallet "pendulum" design requires a striking surface of about two inches diameter minimum x ten to twelve inches of length of material with a density of wood that will optimize the hitting of a 3-5/8" diameter ball. And, the shafts are thin in the direction of the swing (to minimize drag) right? No, they are not.

To whip or not to whip?

Those old Jaques mallet shafts were trimmed down to such narrow dimension--to the breaking point (and many of them did break)--but not from poor design or bad craftsmanship. (The wheelwrights of that era were experts of wood joinery and design.) They wanted the shaft to have maximum flexibility, or "whip" as it was often called. Why? Because the courts were very large (two times the size of a modern court) based upon my inspection of the court in Black Point, Connecticut, reported to be the oldest court in the United States.

And their surfaces were long grass, with "moguls". They were more like golf fairways than the ideal playing surface of today's regulation courts. And, on a court like that, you need to hit the ball as hard and square as possible to give the ball maximum speed so it can "float" over the grass without being affected by all the lumps and bumps. (This technique is still used very effectively by the Egyptian Golf Croquet players.)

Envision this sequence: For a split second, the head remains traveling forward while the shaft flexes back due to impact of the mallet impelling more energy into the ball.

As courts became smaller historically and the grass shorter, this design requirement is no longer so important. Modern shaft design is trending more towards stiff shafts. Flexible shafts are a disadvantage in your making roll shots and pass-rolls, requiring an adjustment in your grip and stance to eliminate all the whip.

|

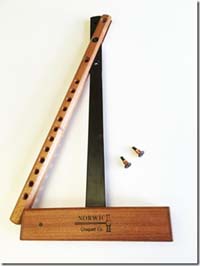

| Here Gordon is assembling the AirGrip "Wishbone" shaft, a Norwich signature design. The grip portion of the shaft is built from White Ash like a "box beam" for maximum strength and minimum weight. The bottom portion flares out into the distinctive wishbone shape, allowing the user to see the ball (through the open mallet center) as it is hit. |

A brief digression is useful at this point, to note that in addition to the "swing" of the pendulum, one can also increase mallet inertia by adding a "punch" component, incorporating into your swing for stop-shots and crouch-shots. The advantage is the top spin given the ball being struck, if you don't follow through. (It's my guess that the exploitation of this effect in the early 1900’s accounts for the 24-inch long mallets in the now-antique game of Roque.)

According to USCA founder Jack Osborn, "By moving your lower hand close to the bottom of the shaft, you will be taking the whip out of the shot." (Pg. 132 / Croquet the Sport) This forces the player into a crouched position, which greatly decreases swing accuracy. Curiously, with modern shaft design tending towards stiffness, the crouch position is no longer required yet is still widely practiced and taught. Flexible shafts are an advantage for "stop shots" which the player engineers to dissipate much of the striking force as quickly as possible.

Swing, stance, and grip must all be considered

John Hobbs explains it on his web site: "The mallets are made with an aluminium or carbon fibre shaft connected to the head with a short piece of tapered nylon. This gives flexibility and reduces shock and the shaft is easily removed. Alternatively the connecting piece can be made of aluminium, which gives no flexibility but feels more positive and may help some people with stop shots and very controlled split shots. It doesn't absorb as much shock on roll shots and you seem to have to hit harder to achieve the same distances." This is why a heavily padded or loose grip also work to your advantage. Mallet head length and design also play a part in how the stop shot works.

The traditional quest for the best all-wood mallet has encountered the historically changing game requirements and court speeds, available affordable materials, and incremental mallet design improvements over the course of more than a century. Shipwrights learned centuries ago that a laminated hollow mast was stronger than the average solid wood mast. So why not apply this proven concept to wood croquet shafts in order to reduce weight?

Let's compare the properties of some popular mallet shafts:

Jaques Hickory with spline shaft / Octagonal grip / String wrap / Weight: 11.7 oz.

Hobbs Aluminum shaft / Nylon grip / Socket / Weight: 10.7 oz.

Hobbs Carbon Fiber shaft / Nylon Grip / Socket / Weight: 9.5 oz.

Oakley Graphite shaft-aluminum / Continuous hard foam grip / 11.2 oz.

Norwich Wood AirGrip / Wishbone split shaft / Octagonal foam grip / 11.7 oz.

Norwich Vagabond / telescoping / collapsible / 15.4 oz.

Norwich SightLine / graphite – wood / nylon / 10.7 oz.

This development has encouraged Norwich to explore the concept of a shaft built as a "box beam", with the lower half of the fore and aft members removed to create a shaft like the one in the photo below. The lower part of this shaft is more aerodynamic than a center-mounted shaft with a roll grip.

| The SightLine shaft is an extension of the mallet sightline rendered in sleek Ash and Carbon Fiber. This "extended sightline" helps you keep the mallet straight as you swing through the stroke – while grasping the familiar, comfortable foam grip above. |

|

And the 1-1/2" length of the wishbone lower shaft helps create a very stiff shaft, which eliminates the need to hold the shaft below the wishbone on roll and pass-roll shots--all of which, theoretically, tends to facilitate a more accurate swing.

|

The Wishbone shaft (combined with an open mallet center) provides an unobstructed view through the mallet and shaft as you cast over the ball. In the Norwich design philosphy, "seeing is believing" eventually converts to muscle memory. |

This design also allows an uninterrupted view of the sightline when sighting, casting over, and stalking your ball. The general advice on the fine art of stalking is to approach your target in a manner that gives you an accurate aim and fosters a deliberate yet relaxed stance for maximum swing accuracy.

Jack Osborn describes the stalk

"Stand from about six to twelve feet directly behind your ball," Osborn writes. "From there, draw an imaginary line from your target, through your ball. Now it is time to walk that line, and only if you are certain that your feet and mallet are aimed properly, it is time to swing your mallet. One of the most important things to realize here is that if there is even the slightest doubt in your mind of your aim, it is your swing itself which will reflect this."

I believe that it was John Riches of Australia who first added a sight line up the mallet shaft to aid in this process. An alternative approach is used when stalking with a split shaft (wishbone) mallet, allowing the player to see the entire sightline on the mallet head. Sighting with a wishbone shaft and rectangular head is quite different and at first seems counter-intuitive. But for many people, it works very well:

All of this works because you can actually sight your ball throughout. This approach can greatly improve most players' games if introduced early in the training regimen.

But again, I digress. Throughout this historical review of shafts, there has also been a revolution in materials. The evolution of shaft materials has gone from wood and cane to fiberglass, aluminum, graphite and composites.

Wood is still the most commonly seen shaft on the croquet court. Increasingly, however, we are seeing shafts of carbon fiber tube, ranging from 5/8" to ¾" diameter, depending on how much flex is desired. Carbon fiber is virtually indestructible. Splinter your wood or fiberglass shaft on a wicket, or dent your aluminum shaft and you can see why carbon fiber is a winner for good, all around mallet design.

Norwich is currently experimenting with a hybrid wood and graphite shaft design, which enables the shaft to be no wider than the sightline in the mallet head--which means the separation of the lines virtually disappear for the player when sighting and stalking.

Beyond wood: the ergonomics of mallet shaft design

The last thread to follow in the eternal quest for "the perfect mallet" is the ergonomics of mallet shaft design.

A directional, properly-sized grip that wrapped with a moisture-wicking string cover was as first seen on Jaques mallets.

The most workable grip compensates for one's "natural" grip while swinging the mallet, which varies from person to person. The proper "grip angle" depends upon the extent to which the grip is cranked from the head axis while swinging the mallet. John Hobbs is credited with a major innovation of a removable shaft with a tapered end which works on the same principles as the Morse taper used on drill bits. It can be adjusted to the precise angle required for a particular player.

| The Graphite shaft features an absorbent cork handle wrapped in a comfortable, black nylon mesh grip. The sliding Roll Grip is a 3-3/4" long, surgical rubber grip that slides to your desired position, imparting greater control of your "pass-roll" shot. Slide it into position and your grip locks it in place. |

|

According to Hobbs "The big advantage of the mallet is that the handle can be rotated in the head so that regardless of how you hold the handle, you can adjust the head to bring it into line." He continues "Many people have experienced an improvement in their accuracy on roquets, due to being able to hold the handle more comfortably and....adjusting the head if necessary."

And finally: the grip should be moisture wicking

Materials which handle the moisture element are many:

- Cork is excellent and should be used more. Percival Mallets in the UK makes a very nice cork handled graphite shaft.

- Unfinished open-pore wood (such as balsa or pine) works well but picks up dirt over time, requiring regular maintenance.

- A foam grip works well, although it will break down over time .

- An overlay of "Duplon" as used on Oakley’s graphite shaft is good at first, however, with the accumulation of oils from the skin, it loses absorption ability over time.

- Grip tape wrap for customizing grip should be considered standard.

Cranking the shaft (angle) from vertical to accommodate natural wrist anatomy is a design option. Oakley is exploring this currently with several variants–based on choice of grip. An additional advantage to this approach is a greater backswing with less effort.

Specialty shafts accommodate individual needs

"Travel Mallets" are becoming more popular as the cost of luggage increases on airplane travel. Typically, the cost is around $40 US to add a threaded ferrule into the carbon fiber shaft, enabling it to be unscrewed. Many mallet makers now offer this option to enable people who travel for tournaments to pack their mallet with their clothes.

|

The Straight Razor shaft takes the SightLine shaft into the realm of easily transportable mallets, with two simple bolts that allow the shaft to fold in half. It fits into a carry-on |

Norwich Croquet Company’s Vagabond Travel/Training mallet has a telescoping shaft for a "one size fits all" solution and can be completely disassembled for easy travel/storage.

| The Vagabond shaft is adjustable from 32" to 38"high. Fully assembled it shrinks down to fit in a carry-on bag. Fully disassembled--as shown above--it will fit into a mailing tube. |

|

Norwich Croquet Company is developing a folding shaft using a laminated wood & carbon fiber "sandwich" which has the added feature of variable flex or whip. Held one way there is no flex in the handle. Turned around there is a "tunable" whip to help on long drive shots & stop shots.

"Walking Stick" mallets (not currently in production) are a fashion/design opportunity.

So much for Gordon Kyle's exploration of mallet design theory and his own understanding of how he has incorporated it into his woodworking business. My hope in writing this article is that other mallet makers will explore a wider range of shaft designs.

Graphite and graphite compounds are popular now, and for good reasons. But a mallet with a graphite shaft is not necessarily always the best choice for an individual player. Therefore and for the same reason, a graphite-shafted mallet is not necessarily the best mallet.

Gordon Kyle is a passionate woodworker who has been described as a "serial entrepreneur." (See https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=J5tnCvGCPAM&feature=youtube.) He is on a quest to prove his theory of "Hive Manufacturing"--which is a model for a self-sustaining, regional, manufacturing resource center. (See:http://www.hivemfg.com/.) One & Co., the parent corporation of Norwich Croquet, is designed and operated as a model of hive manufacturing. Core to this theory of hive manufacturing is the concept of launching a new product every three years. Norwich Croquet is the most recent product launch, with the next going to test market in the fall of 2018.