|

Back to |

| The Front Page |

| The Game |

|

Mallets: Have they gone about as far as they can go? |

|

by Bob Alman with thanks to Don Oakley, John Hobbs, and Gordon Kyle Posted February 17, 2012

|

Most players change mallets many times in their playing lifetime, whether they begin with lightweight equipment in the back yard or on a state-of-the-art fast lawn at an associated croquet club. Serious players--the ones who want to win--discover over time how to match their height and the grip they've chosen with a mallet that ideally suits those characteristics. Less serious players will value the feel and the sheer beauty of the mallet over everything else--the grain of the wood, the whip of the ash shaft of a classic Jaques with brass bindings. Every distributor can give you good reasons for choosing one of their mallet designs. We interviewed some of the best and most popular ones for this update of our 2004 survey article.

In life and in the practice of any sport, sometimes you get stuck and don't know how to move forward, make progress, and get over whatever's stopping you. Sometimes any change works, because it makes you re-focus on the basics and take a hard look at what works and what doesn't, what feels right and what obviously doesn't do the job. In croquet, the most consequential change beyond shoes and hat will likely be your grip and your mallet. They work together, and the one you spend the most money on is the mallet: anywhere from a hundred US bucks to a thousand euros, depending on the design, the materials, the workmanship, and the demands of the technology.

Extending the Moment of Momentum

|

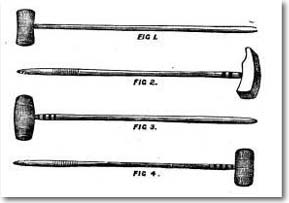

| Throughout most of the Nineteenth Century, the golf-like side stroke was preferred in croquet, calling for short mallet heads suitable for "clubbing" the ball. The physics of the center stance called for an entirely different approach, which is being optimized in the 21st Century. |

Alan Pidcock, the retired chemist who has been the long-time tester of croquet balls approved by the World Croquet Federation and most national associations, is credited with pioneering the application of MOI (moment of inertia) physics to mallet manufacture. The introduction of his 2001 series has proved to be a major breakthrough, as evidenced by the prevalence of that mallet and later generations at top-level croquet tournaments around the world.

|

| This Pidcock "2001" mallet from Manor House epitomized a revolution in mallet-making that required maximizing the benefits of peripheral weighting. The disadvantages of the round head have been addressed in newer models by using "D" shaped weights on the end faces instead of these round ones. |

All the manufacturers and distributors in this article recognize the import of lowering the center of gravity of the mallet and extending the MOI in order to prevent twisting the mallet in the stroke, which results in a miss-hit. This includes Jaques, whose brass bindings placed on the ends of their shafts to reinforce wooden surfaces were, perhaps, the first widespread application of peripheral weighting in mallet design.

Combining all the weight factors into one workable design dictates certain limitations under the laws of "diminishing returns." Most people should not use a mallet that weighs more than 3 1/2 pounds; and most people (unless they're very, very tall and use a Solomon grip) would not do well with a mallet head longer than 12 inches.

To see how your mallet rates in the realm of peripheral weighting, find out where the balance point of your mallet is by holding it up on your wrist. If the balance point is more than a couple of inches from the top of the mallet head, you're still playing 20th Century croquet.

|

| Don Oakley and his partner Diana Ward live and work together and travel often south from their Ontario home with Don's SUV loaded with equipment deliveries to clients between Canada and South Florida. |

"My first generation mallets 20 years ago followed conventional design in shape and size," Oakley recalls. "Around that time, reinforced striking faces were making their debut, so I decided to make our first production mallet from a solid block of high density polyethylene. It offered similar playing characteristics to those of wood but was indestructible and, by coincidence, ended up as the best stop-shot mallet (according to American pro Bob Kroeger)."

|

| The graphite shaft of the lower section of Oakley's new Gryphon mallet is completely encased within a molded EVA foam grip. Oakley comments, "The part I like about the new materials we're using is that it opens up enhanced design opportunities. It's the beginning of a new generation of mallets whose looks can match their performance." Note the stainless steel plates fitted behind a carbon fiber face on the ends of the walnut mallet head. |

In addition to joining the rush to peripheral weighting, Oakley started to address players' differing preferences in shaft flexibility. "As a woodworker of 30 years, I like to use wood but am quite happy using metals and composites when and where each make sense," Oakley says. "Carbon fibre is an advanced material with exciting potential. I've made several 'concept' mallets to explore that potential and get player feedback.

"Our newest mallet, the 'Gryphon', is a result of that testing. Its 9-ounce carbon fibre shaft is stronger and lighter than anything our shop has made before. That helped push the center of gravity further down the mallet. Carbon fibre readily adapts to changes in rigidity, so this shaft also represents a first by allowing us to give customers different flex options.

"The beauty of carbon fiber shafts is that they can get the same whip as a narrow-diameter wooded shaft, as in a classic Jaques, without compromising strength." The Gryphon's mallet shaft is designed to accommodate differing players choices in "whip".

Hobbs' radical innovation in shaft alignment

Stephen Mulliner had a lot to do with encouraging John Hobbs' successful venture into mallet-making in his English workshop, where he has produced about 1800 mallets since he started in 1994. Mulliner had already noticed that the straight-on alignment of the axis of the hexagonal shaft didn't work for him; it was at least ten degrees off. Hobbs' design allowed for easy and fast adjustment by the customer, and Mulliner eventually found that a deviation of closer to 45 degrees fit his Irish grip perfectly. Mulliner's results in tournaments since then argue strongly for the Hobbs method, which Oakley and other manufacturers also make possible in many of their own designs.

Like Oakley, Hobbs started experimenting in his home workshop with wooden designs; soon he accepted the limits of wood in some performance realms relative to carbon fibre, but he felt that carbon fibre "has no soul." According to Hobbs,"To work out what is 'best' for a player depends on what the game is, what the lawn is like and what your body is like. The factors to consider are head weight, length and stability, then handle length, shape, rigidity and whether it is fixed or can rotate in the head."

|

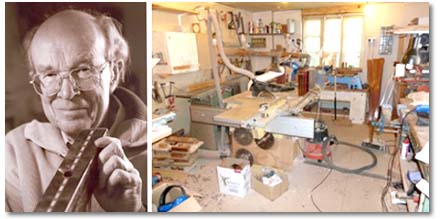

| John Hobbs smiles above a "once-off" mallet with a bad groove cleverly hidden by an especially decorative sightline. "The workshop shows the chaos I work in," he says, "and the third photo (below) shows how beautiful cocobolo wood is." |

|

Among all those variables, Hobbs considers head weight first: "I was once demonstrating stop shots to Association players and used my three-pound mallet to achieve about a 6:1 ratio, which for me is good. I then borrowed a lady's two-pound, eight-ounce mallet and, with no difficulty whatever, achieved a 12:1 ratio. The Egyptians have mallet heads that weigh 1lb 14oz, which is 8oz lighter than average heads in most croquet-playing countries that weigh 2lb 4oz. They can do the most marvelous golf stop shots, but we all know how hard they have to hit to get the ball moving. Furthermore they only hit one pound of ball, not two pounds as in a croquet shot.

"So I now have two mallets that I show customers: a 2lb 15oz for golf croquet and a 3lb 4oz that I find is better for Association Croquet. The heavier mallet gives great stability (both have 12" heads), but the frequent energetic shots in golf croquet mean that it's hard work with a heavy mallet and the lighter one is easier. The loss of accuracy from slightly less stability is less important in golf, because you may only lose one point if you miss, whereas in Association it might lose you the game."

Managing stability in the swing

Hobbs recalls, "I once made a 15" head mallet, but it was too long. I also made a 6" one for a friend and I predicted, correctly, that it would be useless because it was so easy to twist. So, to make a mallet stable you need length with the weight concentrated at the ends. 12" is better than 11" and better than 10” and I refuse to make 9" because they are so easy to twist. Having brass ends instead of plastic backed by lead gives a definite advantage."

The width of the head makes a difference, too: "A narrow head is better because the wood weighs less and more lead can be put at the ends. I also drill out two wide holes in the base of the head, which reduces the wood weight and thus increases weight of the leaded ends."

Here's how Hobbs describes his major innovation in mallet design: "The shafts of my mallets can be rotated in the head, and this confers a definite advantage for the player with standard grip (top hand knuckles forward, bottom hand palm forward). The top of the shaft has an octagonal cross section with one axis longer than the other. If you have the long axis going from left to right and you place your top hand round the shaft you will find it fits comfortably and predictably. However, when you put the head on the ground it will probably be pointing about 15° to the left. You put the head between your feet and twist the shaft until the head points straight ahead. You test the setting by trying to hit the peg from about 10 yards and if all the misses are to one side I tell you how to twist the head to get it central.

"Once it's right you do up the screw in the bottom and the shaft is fixed. Then when you play, you don't have to think about whether the head is pointing in the right direction, which would be necessary if you had a round grip on the shaft."

For players who use the Solomon grip (both hands knuckles forward) Hobbs has found that having the long axis front to rear happens to be ideal, with usually no need to adjust the angle, unless a particular individual is consistently missing to one side or the other.

"For the Irish grip (both palms forward) the same orientation is fine, but some players, including Stephen Mulliner, have found that if you turn the shaft through about 45° it feels more comfortable, so it's worth experimenting with this setting."

Tournament players appreciate the easy and quick disassembly, because it means that the mallet can be packed for airline travel. But what if the shaft is too long to pack? "Just buy a length of rigid drainpipe to wrap round it," Hobbs suggest, "or carry it as a walking stick, accompanied by a suitable limp!"

While Jaques reduces shock with a flexible shaft as well as a spline around their tapered shaft, both Hobbs and Oakley can employ a flexible nylon connector to join an aluminum shaft to the head.

To sum up, Hobbs suggest, "You need a mallet suitable in weight for what and where you play, preferably 12" in the head, with weight at the ends, and which points in the right direction when you are holding it naturally. Failing laser sights, that's the best any mallet maker can do for you!"

Norwich Croquet: Where style meets substance

|

| A quartet of elegant hand crafted mallets by Norwich. |

According to Kyle, "An article in a local paper said that Norwich had played a pivotal role in the development of the American game of croquet back in the 1800's. That was part of the background on a newly re-opened Ocean House resort in nearby Watch Hill, Rhode Island, with a beautiful oceanfront croquet lawn managed by resident pro Teddy Prentis.

"We had been searching for a small- scaled product that would allow the use of our short lumber and our finish chemicals 'left over' at the end of daily countertop production. Limited production, hand-crafted croquet mallets built in a truly "green" process seemed like a perfect fit for us."

After thoroughly researching everything on the Internet he could find on modern mallet design, Kyle formed a croquet club for which he designed and built prototype mallets; he started playing the game himself, and soon Ford Faye, a local croquet fanatic, looked him up and showed him his extensive collection of mallets, which he is constantly comparing and testing. Ford bought one of Kyle's prototype mallets and began a field test that generated numerous changes to his original product.

"Together, Ford and I worked out what shaft design would produce the best long shot on "long grass" lawns- our particular area of interest. Our assessment was that most mallets were too stiff. The older mallets had better action due to a narrower shaft diameter compared to modern wood shafts with broader shafts. A narrower shaft diameter allows for increased flex or "whip" which translates to a longer shot.

"To build a proper wood shaft, one either has to start with quartered lumber or laminate the shaft stock. We chose the latter approach. This allows us to use our "short" length lumber residual from our countertops. Ash is still the main wood species in the shaft because it has the best performance characteristics, but we alternate walnut for a decorative striped effect.

"One of the criticism of wood heads and shafts is that moisture gradually loosens the joint due to seasonal swelling and shrinking. So all our shaft laminations and handle-to-head joints are glued with a West System epoxy, which produces a waterproof joint. We then finish our mallets with our own marine 'Watershed' finish developed 15 years ago for our wood countertops for an overall waterproof finish we can confidently declare to be unsurpassed in the industry."

Kyle is quick to assert that Norwich is not only about the technical aspects of mallet design. You'll note on their website that their designs are fresh and stylish, with nary a straight line anywhere. "We believe a well-made mallet can also be a piece of woodcraft art--something worthy of hanging over your mantel."

Norwich has much in common with the biggest and oldest mallet maker of all, with 150 years of tradition behind a huge variety of mallet choices: Jaques of London, the company who virtually invented the sport. Jaques is the only maker who still offers the traditional favorite wood of mallet makers for its hardness and durability, despite its expense: lignum vitae. On their website, Jaques' huge variety of designs includes a choice of more than a dozen woods, and Norwich, at this early stage of development, uses white oak, wenge, rock maple, walnut and ask and will soon produce limited editions in zebrawood and other exotics as well. The line is augmented with phenolic and other space-age components.

Also like Jaques, Norwich targets primarily the "long-grass" market, for dedicated amateurs not necessarily among the 60,000 or so members of organized croquet associations around the world. Like Jaques, Norwich also produces "sets" of sizes and weights. (Oakley Woods supplies Norwich with the non-wood component parts needed for their sets.)

Whether you play on long grass or in the back yard, one of these manufacturers and distributors is waiting to help you select your ideal mallet. Here are some of the contact points:

SOME MALLET-MAKER CONTACTS

Jaques of London:

Oakley Woods Croquet:

Norwich Croquet:

John Hobbs Mallets:

Manor House Mallets (Alan Pidcock):

http://www.jaqueslondon.co.uk/shop.html

The Jaques website has links to national and regional distributor websites.

https://www.oakleywoods.com/categories/CROQUET/MALLETS-%28ALL%29/

Email to: inquiries@oakleywoods.com. Or call toll-free in America Work: 866-364-8895.

norwichcroquetcompany.com.

Email norwichcroquetcompany@sbcglobal.net or call 860-892-5180.

john-hobbs-croquet-mallets.mfbiz.com;

Email hobbsmallets@waitrose.com or phone +44 (0)1892 852072.

Inquire via the English Croquet Association Website's Online store, at sales@croquet.org.uk; or email Alan Pidcock at pidcock@manorh.plus.com.