|

Back to |

| The Front Page |

| The Game |

|

The slo-mo revolution for referees and spectators |

||||||||||

|

by Bob Alman Posted November 25, 2013

|

||||||||||

|

||||||||||

How do you envision croquet in the year 2050? If the sport is to survive and prosper, I can imagine live cable coverage of major Golf Croquet events, aided by instant slow-motion close-ups of otherwise questionable strokes, played on an interesting terrain court deliberately designed to undulate sufficiently to require players to "read" the turf and adjust their strokes accordingly. With three-camera coverage, Golf Croquet will have matured sufficiently to attract millions to frequent live coverage of a fast-moving and competitive sport. This article is about one fundamental advance that enables that vision to come true--sooner rather than later.

Although most responsible regulators of the sport are now recommending slow-motion video as one of many tools in training referees, at least one expert is proposing this technology as a major tool of tournament referees on the court. As the most fervent advocate of slow motion refereeing, the American pro Bob Kroeger has posted many of his short videos of specific shots discussed on the Nottingham Board, croquet's main email newsgroup.

|

| Bob Kroeger is one of a handful of working croquet pros in America. At the National Croquet Center in West Palm Beach, he demonstrates for intermediate students a jump shot. |

Kroeger--who says he has used this technology eight times already in American tournaments, without problems or issue--is suggesting that the time for using slow motion refereeing in all major events is fast approaching, and has demonstrated the feasibility of this refereeing in perhaps the most trying circumstances in any tournament--the USCA Selection Eights, which calls for constant play in all flights, and "self-refereeing." He got permission from the Event Manager to use his camera, and the first occasion was one of his own shots, in the second Eight, for which his opponent requested a referee. (No one objected to the use of the camera throughout the event.)

The first call--a possible double tap

The opponent had never used Bob's camera, so Bob brought him up to speed in about 30 seconds; there was a "live" referee in addition to the opponent, using the camera. For a brief test, the opponent pressed "record" and then "stop."

The refereed shot was Bob's own, at 3-back, where Kroeger needed to get a long shot in order to roquet a ball near 4-back. There was a clear danger of a crush. Although some referees might have called a double tap , slow motion showed clearly that it did not happen. (This is the first call on the tape https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=OY_Io4FpWNI)

The second call--a double tap?

In this hampered position, the sound might have indicated a double tap. The live referee ruled a fault, and the video confirmed conclusively that it was, indeed, a fault. This was to be the only fault ruled in any of the four uses of the camera as a referee aid in the event.

The third call--a possible bevel

On this through-the-hoop sweep shot, it's possible for a referee unaided by a camera to "see" a bevel shot (or at least "figure out" that one must have occurred.) The slow motion camera, however, saw no such fault.

The fourth call--another double tap?

On this one, Kroeger was the camera person and multi-tasked as the "live" referee. Once again, the slow motion camera clearly and unambiguously revealed a clean shot.

In comparing the real-time and slow-motion views of these shots, it's easy to imagine that some referees would resort to "common sense" and presume that one or more were faults. With the camera as an aid, such "figuring out" need not ever again mar the refereeing of major events. (Rule F5 in the World Croquet Federation regulations for referees warns against referees bringing to any specific call their knowledge of physics or analysis of the physical behavior of the mallet and the balls.)

But the majority sentiment in the croquet world at this time--as revealed by the Nottingham Board conversation on this subject--strongly favors using the camera "for referee training only"--even in the major events where accurate and unambiguous referee calls may properly be regarded as most consequential. (More than one championship has been determined by a referee decision later called into serious question; most of those calls have never been definitively settled.)

Australia pioneers slow-motion video for referee training

Croquet associations around the world are understandably reticent to make quick decisions on such matters, without thorough testing, discussion, and exhaustive exploration of the possibilities and the hazards in their deliberative bodies. The first step towards actually using slow-motion cameras in advanced tournaments will be using them for referee training.

|

| Liz Fleming. |

Surely Australia is the "sportiest" country in the world, and the one with the most organized and regulated approach to the governance of most aspects of croquet, including the active involvement of governmental bureaucracies at several levels which apply to all the recognized sports supported and regulated, to any degree, by national or state bodies.

|

| Liz Fleming--in the dark coat--poses with her squad of referees at the 2012 WCF World Championship for Association Croquet in Adelaide, Australia. |

"Should the rules be changed?" No!

| RAPID ADVANCES IN HAND-HELD TECHNOLOGY |

|

Affordable ultra slow motion video has arrived in the marketplace, with 400 plus frames per second (FPS) as a reasonable baseline for video refereeing. The Casio Corporation continues to lead the way for digital cameras with this capability.

Today a real game-changer is the app for Apple devices called SloPro. SloPro can play back at a number of speeds, but offers at the top range 500 FPS and 1000 FPS, ideal in a croquet environment. This free app does a more than adequate job of analyzing many shots a referee might miss without the aid of slow motion video. Of the various reasons many have given for not allowing slow motion in tournaments, affordability of a slow motion camera has been a legitimate concern which is rapidly becoming a non issue with the proliferation of Apple devices worldwide. The combination of affordability and ready access to hand-held technology should also enable tournament managers of the near future to have cameras at all the venues of a major tournament. Apple products that can host SloPro:

|

Some coaches in the United States actually "teach" acceleration of the stroke as the effective method of achieving a roll shot; the degree of acceleration will determine where the shot falls between "half roll" and "pass roll." The honest ones acknowledge that the stroke is "just a little bit illegal," but that kind of croquet stroke has been learned by millions of players in back yards and parks all over the world, some of whom have advanced to a more serious level of competition, with little adjustment of their croquet stroke technique.

This writer was surprised to find that only Louis Nel among the American bigwigs I asked about this were willing to consider changing the rules to outlaw those likely to be seen as faults when subjected to rigorous examination. I was surprised, because such a change would surely tend to "slow down" the game, make it more interactive at top level, which is becoming an ever more serious concern in every country as the regularity, speed and consistency of courts everywhere are being advanced; and for spectators, the highest level of achievement in the game produces very long exhibitions of skill which are, however, stupefyingly dull to watch.

Liz Fleming and James Temlett are in the front line of those who firmly oppose changing the rules of the game, although Liz comments, "If the slow-motion sequences used in our training were to simply show every shot being played magnificently well, neither players nor officiators would learn very much from it." She wisely observes a fine line between a clean shot and a fault-producing one for "innovative players who are ever searching for ways to gain an edge with a nifty little sweep or a quick little jab here and a little poke there--players who can be a pretty ingenious lot once a referee has been called into the game."

|

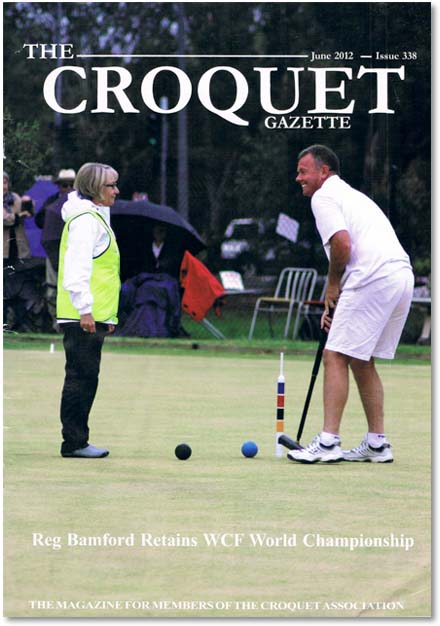

| The relationship of the live referee and the player comes across clearly in this magazine cover on the peg-out of Reg Bamford winning his umpteenth WCF World Championship title in Association Croquet in Adelaide, Australia, in 2012 with Liz Fleming looking on. Liz comments, "This was a magic moment for both of us and obviously demonstrates the overwhelming joy of instantly being able to share it with another human being." Photo by Elizabeth Williams. |

Without an intention to deliberately deceive, even a highly-principled player, when being refereed, would unconsciously try to make a "clean presentation" by any means. Will this be seen by "the naked eye," or only by slow-motion video? And given the long tradition of the sport--including the way croquet shots are taught an played--does it really make that much difference?

What is done in the sports of Golf and Tennis

In the Nottingham Board conversation on this issue, Samir Patel posed the question, "...if the decision made by the referee on the spot can be improved by reference to additional evidence (such as video evidence) *prior to the expiry of the limit of claims* then isn't that a good thing?" Patel also quoted from official announcements to golf associations in both Europe and America, pointing out that "adapting to developments in technology and video evidence is an important ongoing topic in making and applying the Rules." The announcements further noted that "regardless of the timing or the type of evidence used, the integrity of the game is best served by getting the ruling right."

Even if there's a changed or adjusted ruling in a golf competition, it can be changed later, by adding strokes to the player's total; but that cannot be done in croquet, where one ruling can drastically affect the overall result, and the referee's decision cannot be "reconsidered' except in the turn to which it applies.

Tennis provides the best example from another sport of the level of certainty that could be achieved by "instant" slow-motion replays of doubtful shots. But golf and tennis are huge sports, worldwide, with fully developed, complex, and expensive technologies behind the "instant replays" we routinely see in telecast matches. Although a similar level of sophistication can be envisioned for croquet, one cannot realistically expect it to happen achieved any time soon.

But Bob Kroeger's proposal for use of slow-motion videos to aid "live" referees is, on the other hand, an easily envisioned interim step, especially with the recent advances in hand-held telephones and applications whose use he has demonstrated at the USCA Selection Eights.

The referee training delivered by Liz Fleming and others in Australia will doubtless be the "acid test" to which this new and advancing technology will have to be subjected, perhaps over the course of several years, before routine use of camera-aided refereeing in major events is adopted worldwide.

|

WHAT OFFICIAL RULINGS SAY ABOUT MALLET FAULTS

In the 2008 revision of the Laws of Association Croquet, mallet faults include instances in which the striker:

"(A) in a croquet stroke, or continuation stroke when the striker's ball is touching another ball, allows the mallet to contact the striker's ball visibly more than once; or "This sub-law covers both multiple and unduly prolonged contact between the mallet and the striker's ball.... High speed photography shows that many croquet strokes, which to human senses are perfectly acceptable, do in fact have multiple contacts, and contact times considerably longer than single ball strokes. "To ensure that the game remains playable, a laxer standard, namely that the multiple contact must be visible, is applied to croquet strokes......"Visibly" means capable of being seen by someone with normal eyesight standing in a good position to observe the stroke..... It is not enough, for this sub-law, for the hypothetical observer to deduce that there must have been multiple contacts by analysing the physical behavior of the mallet and balls." Unless "a little laxity" is allowed, the game would surely be significantly altered. Many croquet strokes and virtually all "roll" shots would have to be outlawed. Few bigwigs in any organized association would want to see this happen. Although it would result--minutely and temporarily--in making the game more interactive at all levels, there is general agreement that it would not be good for the sport at any level. The burden will remain on referees to make final determinations on such murky adjectives as "appreciable" and "observable," and "unduly prolonged." To do that, the officials who train those referees need to agree upon and apply consistent standards. |