|

Back to |

| The Front Page |

| The Game |

|

How Lord Tollemache's Croquet helped shape the game's development |

||||||||

|

by Mike Orgill photos and illustrations scanned from Lord Tollemache's book layout by Reuben Edwards Posted September 27, 2015

|

||||||||

|

||||||||

The posting of Don Gaunt's book for beginners and improvers, Plus One On Time, put me in mind of another book published just over 100 years ago. Croquet by Lord Tollemache stakes out somewhat similar territory and aims. Gaunt's book deals mainly with handicap games and offers no technical instruction. Tollemache has a broader focus, covering the full range of croquet techniques and the strategies of his time. Gaunt aims to guide his readers toward handicap croquet excellence and perhaps advance to the "scratch" game. Tollemache sought to enable players to climb "from the bottom of the 'A' class to the top." Viewing croquet through Tollemache's lens shows how much the game has changed and how much has remained the same over a full century.

If Keith Wylie, author of Expert Croquet Tactics, is the Oxford don, secure in the seeming impenetrability of his arcane knowledge, Tollemache is the beloved uncle ensconced in his library on a rainy day, dispensing ground-level wisdom with cigar and single-malt in hand.

|

Bentley Lyonel John Tollemache, the 3rd Baron Tollemache, known to the croquet world as Lord Tollemache, was born on March 7, 1883 and died January 13, 1955. He was the owner of a 35,726-acre estate in Suffolk, Cheshire and other counties in England. His military service included stints in the Boer War and World War I in which he was wounded and retired as a captain in the Royal Garrison Artillery.

Aside from Croquet, he wrote Croquet: hints on "practice," "tactics," and "stroke play", (1923), and Modern Croquet Tips and Practice (1947), and in addition, works on bridge.

The Stanley Paul first (and only) edition of Croquet appeared in 1914. The book's publication was the capstone of the Edwardian golden age of croquet. As Croquet hit the bookstores, the Edwardian era itself was coming to a shocking end. By August 1914 Austria-Hungary and Serbia were at war. England was soon to follow. For the privileged classes, without any understanding of the catastrophe to come, the social world looked to go on as before. Croquet looked ready to be transformed, with evolutionary change to the nature of the game very much in the air.

The Stanley Paul first (and only) edition of Croquet appeared in 1914. The book's publication was the capstone of the Edwardian golden age of croquet. As Croquet hit the bookstores, the Edwardian era itself was coming to a shocking end. By August 1914 Austria-Hungary and Serbia were at war. England was soon to follow. For the privileged classes, without any understanding of the catastrophe to come, the social world looked to go on as before. Croquet looked ready to be transformed, with evolutionary change to the nature of the game very much in the air.

|

Just before the world crisis would dawn, on a page that also featured a lovely drawing of fashionable ladies headlined "The Popularity of the Four-In Hand During the 1914 London Season", (the "Four-In-Hand" being a carriage with four horses driven by a single driver), the June 20, 1914 issue of The Sphere summed up the croquet season so far:

"Croquet is very far from being the grandmotherly game . . . [for] the best players in open tournaments it is an exceedingly skilful game. Big breaks are not to be made by the mere tyro, breaks which should be easily possible were the game as simple and puerile as it is so often painted by those who lack acquaintance with it and its manifold difficulties. . . .The game as known to-day is a very different game from that which was incepted under the name back in the seventies, for it has been evolved out of many changes and may possibly still be regarded as subject to the evolutionary process. "

As hundreds of thousands of young men were about to be crushed in the maw of war, The Sphere's correspondent wrote:

"Quite natural is it that this should be the case with a game which is yearly attracting a large body of young recruits somewhat more skilful perhaps than their forebears, and a year ago the laws were altered so as to provide for alternative games with a view to assist the out-player. Considerable opposition has made itself felt, however, in regard to the merits of the changes, the chief of which was that permitting either of its balls to be played with by a side when the opponents had finished their turn."

World War I may have also destroyed any chance croquet had of being a major world sport; those "young recruits" were about to be deployed to the trenches of the Marne.

More from The Sphere:

"And now we have that great player and theorist, Lord Tollemache, propounding a series of changes which . . . would undoubtedly revolutionise the game as we know it to-day."

It seems that Tollemache is proposing a square court:

"Indeed, it could not well be the same game seeing that the proposals require a new court -- square instead of oblong -- and hoops which would have to be run from outside circles rounding them, whilst the two balks would be replaced by four."

|

Just as the Association game was being born, the hoary "sequence game" was being pushed to the side. And less than two months later, the August 1, 2014 issue of the London weekly, The Spectator, is filled with news of war and rumors of war. Skimming forward in the issue to the book review section we see, along with tomes dealing with photography in the tropics, the history of British banking, and gnomic poetry in Anglo-Saxon, a capsule review of Lord Tollemache's Croquet:

"A high authority in the croquet world," [the anonymous reviewer wrote,] "recently asserted that there were not more than half-a-dozen players who could play a four-ball break in its ideal perfection. Lord Tollemache's eminently practical book ought to add largely to that number, since he gives full details of the best methods which he is in the habit of employing. Numerous photographs and diagrams enhance the value of the work, which should be in the hands of every croquet player who aspires to improve his or her game."

This "high authority" was probably Tollemache himself. This whisper of information from croquet's dim past shines quite a light on pre-WWI croquet. How different the competitive standard must have been in those Edwardian days! Today most tournament players find the four-ball break a trivial exercise, and the croquet elite in Great Britain have instituted "Super-Advanced" laws to retard the equally trivial triple peel. The croquet world today struggles with ideas for changes that would make the game more interactive.

Croquet touches on the game we play today, what Tollemache dubs "the either-ball game", but gives it shorter shrift. The Edwardians played a sequence game, like the USCA-rules game but without deadness. Their court featured six hoops, but there are two pegs, the first located directly below the fifth hoop, and the second, dubbed the "turning peg", located directly above the sixth hoop. The player is required to hit the "turning peg" with the striker's ball (which gains the player an extra stroke) before proceeding to one-back. The endgame peg-out occurs at the peg below hoop five. There is no peg between hoops five and six, which are closer together than in our current layout. (Our six-hoop "Willis setting" was officially adopted by the Croquet Association in 1922.)

The first eight chapters deal with matters of technique: hitting the ball, stop-shots, rushes, etc. There are three chapters on two-, three-, and four-ball breaks. The remaining chapters deal with strategies relevant to the ancient game of Tollemache's time, along with a couple of chapters exploring strategies for the emerging "either-ball" game.

Croquet's binding includes a pocket in the back containing a large court diagram (which the reader should use to follow along with Tollemache's detailed play descriptions), eight other smaller diagrams describing specific plays, and twelve coin-like markers representing the balls. (Many editions on the market are missing these pieces.)

Given that the game Tollemache describes is obsolete, and his

"either-ball" tactics are rudimentary, the main value of Croquet lies in

Tollemache's sage comments on croquet technique and the mental game, and

the book's many photographs of Tollemache demonstrating croquet

technique. Many of these photographs were taken on Tollemache's private

court at his manor house; others were taken at clubs--Hurlingham

perhaps?

Given that the game Tollemache describes is obsolete, and his

"either-ball" tactics are rudimentary, the main value of Croquet lies in

Tollemache's sage comments on croquet technique and the mental game, and

the book's many photographs of Tollemache demonstrating croquet

technique. Many of these photographs were taken on Tollemache's private

court at his manor house; others were taken at clubs--Hurlingham

perhaps?

Beginning the book, Tollemache wastes no time on surveying the game or describing its history; he assumes his reader is in no need of that. He plunges right into a dissertation on "styles"--that is, how to hold and swing the mallet.

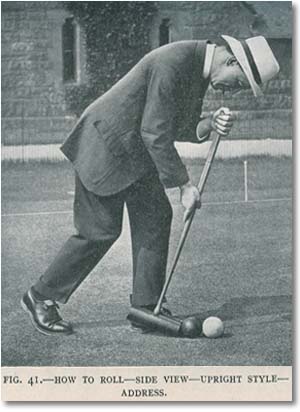

One "style", the "upright", is obsolete in Tollemache's time, and is rarely seen in our day, unless the contemporary player needs to do a long roll shot on a slow court. The "upright" or side style is useful if you are a fashionable lady with voluminous skirts which make any swinging of the mallet between the legs impossible. (The photograph of lovely Lady Lucian Parr perfectly illustrates the style.)

|

Tollemache advocates the Irish grip in which "the fingers do most of the work." He finds it somewhat tiring and sometimes lacking in power, but what it lacks there it more than makes up in accuracy, since the "upright" style singularly fails at both the long rush and the six-yard roquet. "

Moving on to more general principles that are so important that "they should be printed under the number of each court," Tollemache writes: "Pay the whole of your attention the whole of the time to what you are doing. An absolute concentration of thought throughout the game, whether you are playing or not, the whole of the time, is the first principle of croquet. If this book contained nothing but this on every page, I consider it would be worth its place in the sun."

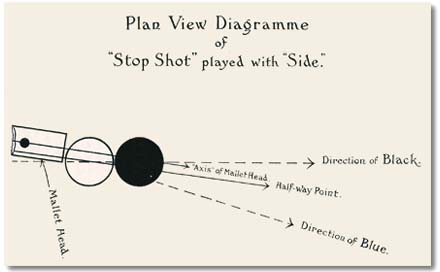

The chapters on stop-shots, roll shots, etc. offer advice and technical hints that can be gleaned from many instructional manuals published since Tollemache's time, but the Lord offers his own idiosyncratic take.

On the stop shot:

"I caution the reader against making a hesitating sort of poke, caused by the rather natural fear that his ball will not "Stop". . . .Where a great amount of "Stop" is required, you should always play for a position that will enable you to place your ball slightly off the straight. Then, when your ball is to go the right, use the right-hand edge of the mallet, and vice versa. First aim the mallet dead true, then move it about an inch or so to the side, but parallel to the old line. . . .Your aim should be made as if you were actually going to hit the Object ball practically full with the face of the mallet."

|

On the full roll shot:

"Your hands must be right in front of the head of the mallet. They should remain so until well after the balls have gone. At the finish they should be well above the head of the mallet. The wrists should be as rigid as possible. In the Irish style the hands should be well in front of the shaft. This allows the fingers to draw or sweep the mallet through. If much power is required, it is the stomach muscles that must supply it mostly."

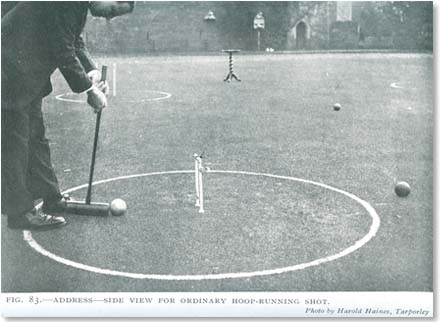

On running hoops:

"I particularly caution the player against moving his head and shoulders. It is the mallet head which should move and the movement of "everything else" should be reduced to a minimum. . . .The mallet should be drawn back quite slowly, toe first, along the ground, before being raised at all. The wrists should, on no account, be allowed to bend in the up sweep more than they were when the ball was at rest."

On the split shot:

"Right-handed players will always find a greater difficulty in being accurate when their own ball has to go to the left. They will find it far more difficult in this shot to follow through dead true on the "Line of Force." There will always be a great temptation to follow-through too much on to the point where the Pilot has to go. . . .Try to imagine the Pilot ball is a wall, and that you are driving your own ball against it. If you drive your ball at a dead right angle to the wall (dead opposite to you) your ball will return direct to you. If you drive your ball to either the right or the left of the spot dead opposite to you on the wall, your ball may be said to hit the wall at an angle. The ball will return towards you, but it will leave the wall at exactly the same angle at which it hit it, and will arrive to one side of you at a point which is exactly twice as far from you as the point on the wall dead opposite to you. In other words it will glance off further to the side than ever. This is exactly what happens in a split shot."

Other tidbits from Tollemache:

"The careful, cautious player [Aunt Emma, though he never uses the term], is the 'cancer and tuberculosis' of croquet. It is an insidious disease, easily caught and difficult to cure."

[Hitting your ball] is "the only difficult thing to do in croquet."

"If you want to be first class, you must be content to lose game after game in the effort to do things the right way."

"The cause of nerves is mostly ignorance."

"Train yourself from the very start to play each separate shot as perfectly as possible."

"However simple a shot, try to make a fine art of it."

"The painstaking player is the man who takes infinite pains to play each shot by exactly the right method with absolute accuracy. . .to produce a perfect shot every time. This is only way to get to the top."

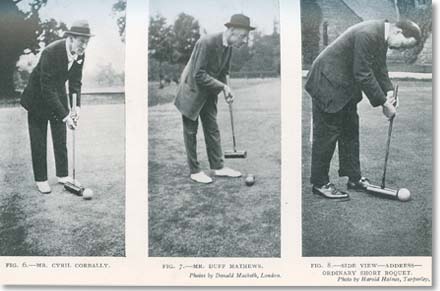

Croquet's copious and amusing photographs instruct the reader every step of way.

|

What happened after the courts fell vacant and tournaments became memories? A page in the June 24, 1915 Illustrated Sporting and Dramatic News provides a glimpse:

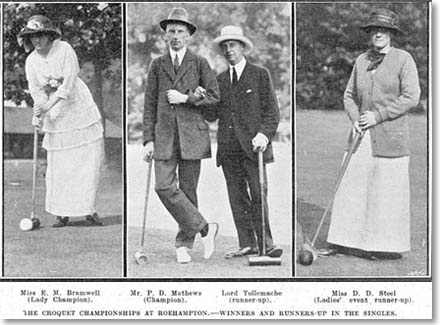

"It will be a source of satisfaction to croquet enthusiasts in all countries to know that several of the strongest Irish exponents of the game have responded to their nation's call in her hour of extreme trial. That the present holder of championship honours, Lieutenant P. D. Mathews, should have been one of the first to join the ranks is particularly gratifying, while the recent promotion of Captain C. L. O'Callaghan, the winner of two championships and a brace of champion cups, is also a pleasing feature, and one which reflects additional credit on the Emerald Isle as far as croquet players are concerned. Other well-known Irish exponents who are undertaking war work of a practical kind are Lieutenant H. S. G. Butson (who has been lost to the game in recent years), Captain G. D. Lister (who was wounded last August and is now a prisoner-of-war), Lieutenant A. St. Leger Taylor (Royal Field Artillery), and Lord Tollemache (Royal Naval Air Service). It was only through delicate health that Second-Lieu-tenant J. B. Moffat (a young Irishman still in his teens) came to take up croquet. His marked progress at the game is almost without precedent, and with renewed health he is now a Second-Lieutenant in the Dublin Fusiliers. Comparatively speaking, the home country does not furnish such a good record. Notable exceptions are, however, forthcoming in Lieutenant H. Maxwell-Browne (an ambidextrous player who won the Champion Cup in 1911 and who gave up an appointment in South America to enlist), Captain R. C. Longworth (one of the most improved players of recent years), Lieutenant H. W. J. Snell (Champion Cup holder), Lieutenant K. H. Izard (who, although a New Zealander by birth, learnt all his croquet in the Mother Country), and Sir C. B. Locock (who is now a motor driver to the Artillery Staff). In their medical capacity the following strong exponents, Doctors E. K. Le Fleming, W. F. Pirn (holder of the Irish Championship), and C. E. Pepper, are also doing useful work. A special reference is due to Lieutenant J. Tuckett, who, on his only appearance in this country two years ago, proved himself worthy of being ranked amongst our best players."

In Croquet's many photographs we see Lord Tollemache, attired in a formal dark suit, blissfully unaware of the world catastrophe to come. After 1914, croquet, and everything else the Edwardians held dear, would come crashing down.

How many of these stalwart croquet warriors came home?

Mike Orgill, long-time and current president of the celebrated Sonoma-Cutrer Croquet Club in Northern California, is a 2015 inductee into the Croquet Foundation of America's Hall of Fame.