|

Back to |

| The Front Page |

| Letters & Opinion |

|

Why they say it's okay to cheat at croquet |

||||||||||||

|

by David H Drazin posted July 27, 2008

|

||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||

The British co-editor of Croquet World Online Magazine was recently incensed by a phone call from a major daily proposing to cover the annual British Opens. The writer was interested in only one thing: "Tell me why croquet is proud to be such a nasty game," he demanded. Our editor, of course, did the right and prudent thing: he took a deep breath and tried his best to direct the writer's attention to the reality of the sport of croquet as played at championship level, as distinguished from the backyard game that rules the public's imagination. Why do mainstream writers and editors keep harping on "nastiness", which plays so small a part in the organized sport? And why the assumption that,even at the top level, it's all right for smart players to make up the rules as they go along? We asked our resident croquet historian for the explanation we knew he would supply. Here it is.

Open any croquet rulebook, from anywhere of any time, and the independent observer may well believe that he has hit upon a cheat's charter. How a ball is struck on its own or in contact with another; how it is propelled through a hoop; the basic moves of the game; all are subject to rules or laws whose application can only be determined by skilled judgement of a much higher order than can reasonably be expected of the players.

So the observer might properly conclude that it is a mug's game. But there he

would be wrong. For millions of players from different walks of life, whether

coming to the game as an occasional diversion or competing at the highest

level, have agreed that it is too good to pass by. If the game can survive only

by rigorous regulation, then so be it: But the quality of regulation required

to provide an acceptable game will necessarily depend upon the requirements of

the players. So variation will prevail. Too little regulation and you get too

much cheating, while too much regulation and the game becomes tedious.

So the observer might properly conclude that it is a mug's game. But there he

would be wrong. For millions of players from different walks of life, whether

coming to the game as an occasional diversion or competing at the highest

level, have agreed that it is too good to pass by. If the game can survive only

by rigorous regulation, then so be it: But the quality of regulation required

to provide an acceptable game will necessarily depend upon the requirements of

the players. So variation will prevail. Too little regulation and you get too

much cheating, while too much regulation and the game becomes tedious.

|

| "The umpire would have no way of seeing what went on under the ample crinoline..." 'The croquêt', illustration in Jaques's 1864 best-seller, Croquêt: The Laws and Regulations of the Game. John Jaques, Croquêt: The Laws and Regulations of the Game (London: Jaques and Son, 1864) |

So the backyard and club games are very different, and it has to be admitted that the backyard game is the more interesting with respect to the variety of allowed behaviors. At no time is cheating more rife than when there is no official law-making body. Writing of Cheating, Gender Roles, and the Nineteenth-Century Croquet Craze in the Journal of Sport History, 1998, Jon Sterngass of the Department of History, Union College, NY, looked for evidence of gender differences in propensity to cheat, and was inclined to conclude that in certain social contexts women were virtually expected to do so. But the desire to take advantage above and beyond the acknowledged rules of the game is very deep seated in either sex. Everyone knew "All's fair in love and war" and applied the maxim to social croquet as well. So the keen player, man or woman, may be tempted to steal an advantage, or the reluctant player dragooned to make up numbers may get more satisfaction from deliberately subverting the game than by playing strictly according to the rules.

|

| The King and Queen of Hearts, ex officio umpires, in earnest discussion on court. John Tenniel in Lewis Carroll, Alice's Adventures in Wonderland (London: Macmillan and Co, 1865) |

Algonquin Round Table croquet was a free-for-all

|

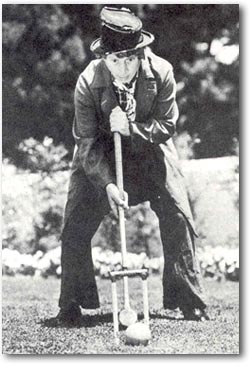

| Alexander Woollcott in play. From Samuel Hopkins Adams, Alexander Woollcott: His Life and His World (London: Hamish Hamilton, 1946) |

Alexander Woollcott, who led the Algonquin Round Table of media celebrities in the 1920's and 30's, prized winning above all, and set out his croquet ground on a far-from-level playing field at Neshobe Island, NY. In his biography, Alexander Woollcott: His Life and his World, Samuel Hopkins Adams writes of his lawn, 'hewn out of virgin forest, with the contours of a roller coaster and frequent extrusions of primordial rock or giant tree root'.

You get some idea of the spirit in which the game was played from Margaret Case Harriman's account in The Vicious Circle: The Story of the Algonquin Round Table. 'Their croquet was a kind of ferocious golf, with the wrong tools, and no limits. Once, when Woollcott drove Harpo Marx's ball into the woods for the third time, Bea Kaufman found Harpo sobbing his heart out against a tree. Another time, the entire Round Table stopped speaking to Harold Ross for almost a week because he had shoved his ball with his foot. What they objected to was not his cheating at croquet, but his insufferable air of innocence as he looked up, caught in the act, and inquired, "But aren't you supposed to?"'

|

| Harpo Marx, said by some to be Woollcott's favorite son. James R Gaines, Wit's End: Days and Nights of the Algonquin Round Table (New York and London: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, 1977) |

But perhaps Potter's most penetrating contribution to gamesmanship was his rule of Clothesmanship, now rendered largely obsolete in tournament play by the current fashion for whites: 'If the opponent wears, or attempts to wear, clothes correct and suitable for the game, by as much as his clothes succeed in this function, by so much should the gamesman's clothes fail'. And he illustrates the application of this rule by appending a caption to Leonard Williams's well known frontispiece dedicated to Roquetetta, depicted with the 'wrong clothes in which Miss E. Watson beat Mrs. de Greim in the Finals of the Waterloo Cup Croquet Turney, 18th August 1902'.

Not unnaturally, cheating in championship play is treated with the utmost delicacy. Players and critics alike are reluctant to put the boot in by naming names or specifying offences, perhaps in recognition that in an amateur sport a player's reputation is his most precious asset, perhaps out of a sense that 'there, but for the grace of God, go I'. So no more than a few months after the conference at the Charing Cross Hotel, London, at which the Conference Code, the first code of laws to receive general recognition, was cobbled together, we have the first major spat in which there was a whiff of cheating.

In the second deciding game of an Opens semi-final, played on 1 July 1870, the umpire failed to spot that Walter Peel continued his turn, in which he pegged out, after rushing one of his rover balls onto the winning peg, and accordingly awarded him the game, an award confirmed by the tournament referee notwithstanding the protests of the defeated adversary, Walter Whitmore. But note that Whitmore's ire was not directed at Walter Peel, the putative offender, or at the umpire for his negligence, but at the tournament referee, John Henry Walsh, for his failure to accept the evidence of bystanders as he had in a recent game between Whitmore and Muntz. Only a few weeks later, in a letter to Land and Water, Whitmore writes of Peel, his cousin, 'who most certainly has the reputation of being the best croquet player in England'.

|

| Lily Gower, 'Lady Champion of England' from DMC Prichard, The History of Croquet (London: Cassell, 1981) |

But since Prichard wrote in 1981, the game of croquet has made enormous strides. Standards of play, playing surfaces, and equipment are vastly improved, and the administration of the game at major tournaments, enshrined in the laws and regulations authorised by national and international associations, is now much more exacting than it ever was. Against this background, there can be no future in the taking of advantage by the habitual or intentional execution of striking errors. But that does not spell the end of cheating. Three types of cheating - opportunistic, pragmatic, and psychological - are still possible and, human nature being what it has always been, are presumably still practised and can never be rooted out, by the nature of the beast!

Subtle forms of cheating that persist: opportunistic, pragmatic, psychological

By opportunism we mean the advantageous construction of doubt, for example the conclusion that a distant roquet has been made when perhaps striker's ball fell short of the target ball by the smallest fraction of an inch. In few cases would a spectator have a better view of the incident than the player and, in any case, so what!

By pragmatic we mean casual or systematic stealth, or abuse of the striker's responsibility as referee of first instance - for example, by replacing striker's ball on the yardline a tiny bit one side or the other, to avoid a contact and so create the opportunity for a rush. Again, neither adversary nor bystander would have a good enough view to mount a challenge, so no one would ever know. And humans have a well-known and copiously documented propensity to see what they want to see; and not to see what they don't want to see.

Undoubtedly the most fascinating form of abuse now practised is psychological, 'the art of winning games without actually cheating' that Potter wrote about - nothing so crass as the placement of an artificial tree. For example, knowing that his opponent is a stickler for silence, the erstwhile cheat will take every opportunity to disturb his concentration by commenting on the progress of the game or by chatting with spectators. Gamesmanship redivivus! And of course the very fact that the game necessarily involves the interaction of two players (or sides) means that gamesmanship is inevitable: even if a player deliberated avoids conducting himself in such a manner as to disadvantage his opponent, his very deliberation may have that effect.

We can only guess as to the true intentions of a player who may be merely careless or thoughtless; who might have seen something happen that others didn't see at all, but honestly insisted on the point; or who deliberately designed and carried out the necessarily evil trickery that denies an opponent an honest win. Mercifully, perhaps, in specific instances we can never be sure.