|

Back to |

| The Front Page |

| Letters & Opinion |

|

Does your brain control your mallet? by Dr. James Temlett layout by Reuben Edwards posted May 4, 2013

|

Frame of mind, concentration habits, and strategic planning ability are all related, and they all impact your results on the croquet court. Primates differ from all other animals by the size of their brains. Human primate brains possess complex interconnections that establish memory, behaviour, and frontal planning, as well as motor control. Sometimes we use all these components well and creatively; sometimes with less salutary results. Why do intelligent players of Association Croquet behave like this?

With this mystery in mind, I have selected for comment a few relevant limbic and frontal cerebral emotions which may affect your planning strategy in a croquet game. While all these ideas play a role, conscious or subconscious, they are highly speculative, and many of them you may declare to be incorrect, subjective, and wrong for you personally. We are inherently all different personalities, and this happenstance makes both life and croquet more interesting. It explains, among other things, why different players of similar intelligence levels will employ different strategies for precisely identical situations.

Part of the great fun of Association Croquet is creating mental foiling in both attack and defense. We are willing to hatch Machiavellian plots to outfox our opponents, just to win a croquet game. Croquet temperament also influences consideration of one's intrinsic strengths, both short term and long term. Knowing yourself will help to eliminate or reduce fears or concerns that impair your ability to withstand competitive pressure. Sadly sometimes, cerebral function may be limited by diseases, but that is not the thrust of this article. This article examines neuropsychological factors that affect relatively normal and healthy people, not the degenerative or neuropsychiatric aspects of aging brains.

|

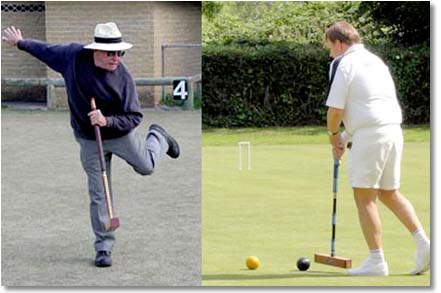

| The frontal lobe is used for planning and executive functioning, but complex deep interconnections govern overall motor execution of a mallet swing and critically influence how a shot is played. Exactly where the croquet balls arrive may depend on balance, momentum and strength of the shot, along with accuracy of the direction of the swing and follow-through. |

Good practice habits and innate sporting ability will provide a sound foundation for a potentially great player. But the game's psychology can tip the emotional balance either positively or negatively--either towards the winning edge or into the "consolation ladder."

|

| Paddy Chapman captured Martin Murray at "full extension," suggesting a near-loss of control to maintain balance. |

Croquet's sporting origins as "garden croquet" on the elite upper class lawns in the late 1800’s evolved to the Association Croquet we know today as a fiercely competed contest, open to both genders and all social classes of all ages, and all professions, from artisans to scholars. Wherever or however you play, the more craftily you outthink and outplay your opponent, the more likely you will emerge the winner-- whether as an individual, a team, or a country--in each game or match you attempt.

Managing partnership and team play

What characteristics constitute a good partnership? There have been enough croquet divorces to prove that we should discourage spouses playing as partners. But what about "regular" partners you don't sleep with? In both cases, it's always best to get the partner's consent to whatever shot or tactic is attempted, by either player. Whatever happens, it is then the partner's responsibility, or more accurately, the responsibility of the partnership. Both partners need to agree to accept the outcome, regardless's of whatever risk-versus-gain equation figured into the final choice.

Surely Cotter and Solomon (who have never been equaled in doubles Association Croquet), defined perfect partnership accord when they wrote, "We just play our own game, and never say what I would do unless asked or planned, because we simply would have almost always played the same shot in the circumstance." But not of all of have this degree of trust in our partners, or our partners in us. I have seen partners come to blows on the lawn, hurl abuse from the sidelines, screaming, "How could you DO such a thing?" It's not a good idea to generate a horrible scene like that, and you don't need to: You just have to know that in the partnership game, both partners need to get to the peg before the opposition.

Get acquainted with the opponent in advance

Knowing or attempting to learn something about your opponent is part of being well prepared for a croquet game. Knowledge of an opponent's skill, likes, dislikes and personality can contribute powerfully to your winning temperament and confidence. A top player said he studies the upcoming opponent's recent form and past years' web site records, and if he finds the opponent was beaten so many times, and derailed by a lower handicap, he used this knowledge and insight to help him to remain less intimidated and more positive.

So examination of past tournament records, the influences of weather upon the opponent, (rain, wind, heat or cold), or fatigue resistance could all be relevant to informing your best play for a particular match.

Equally, observing body language during a game and knowing the record of the player's results so far in the day can give you valuable clues. In sum: try to know your opponent as well as you know yourself.

|

||

|

Insight into an opponent's level of ability and style of play also can dictate what you should attempt or not attempt in match play, or should instead reserve for the next practice session. Complex shots really need to be practiced outside real-game situations. As the out player, concentrate on the dimension of the entire game, always anticipating when you might be called on to play again at any moment.

Taking into account introversion and apathy

Personality quirks affect all of us to a degree. If I am drawn to play the world's number 1, I just know I am going to lose. If I believe otherwise, I obviously have no insight or judgment. The FACT that anyone in the top 50 could beat him/her on a given day does nor enter the mind of the 200th player on world ranking.

But what if the superior player has a bad day? You KNOW you can go round nine hoops, then twelve hoops, and finish the game if he/she misses just two long shots. With your good leave, your opponent's missed long shot, and your well-executed break, you should know that it's actually possible for you to beat anyone--on a given day. (This is on your opponent's “bad day" remember, not a frequent occurrence, but possible.)

Reg Bamford recently gave a motivational speech on this aspect of competitive play and many other aspects of the mind set in Croquet. It was interesting that he found it useful to debunk the “fear of the opponent," as surely as he avoided telling himself, ever, "This is surely an easy win for me!" (Consider his astonishing come-back from down 6-2 in the deciding game of the Golf Croquet World Championship to imagine how he must have been managing his mind in a situation of almost certain defeat.)

Of course there is a wealth of wisdom in the Reg Bamford tape. And yes, it helps a little to be the dominant Association Croquet player over the last decade. But even Bamford arrives early in his best car, well groomed, prepared, in his most sparkling whites, having “visualised” in his mind what he will be required to do to play perfect croquet against a particular opponent on a given day.

|

| Reg Bamford regularly uses his swing trainer to reinforce the "muscle memory" required for a straight swing; but that's only half his winning formula. Chris Clarke commented following Bamford's spectacular performance winning the 2013 Golf Croquet World Championship, "Reg has two 'mannerisms'. The first is that when he plays a poor stroke, he wipes his forehead to “get rid of the memory” – this is perfectly reasonable. The second is that when his opponent plays a poor shot, Reg stares at them--sometimes for up to 10 seconds." Later, Reg explained, "If I’m guilty of anything, it’s copying what my opponent does. If Ahmed’s going to play silly buggers with me – glaring at me every time he makes a big hoop, unnecessarily asking me to move from his peripheral vision, and swaggering around like a heavyweight street fighter in front of his adoring home crowd – he won’t find me backing down. Court 1 in Cairo, sunken and fenced, the thick humid claustrophobic air, under the floodlights, mobile phones deliberately going off on your backswing, constant chatter as you take your shot, chewing gum on your line ball, the ball-boys and their dodgy line calls, the Call to Prayer, a baying crowd – it’s easy to get intimidated when Ahmed finds his mojo. It felt like a civilised version of cage fighting on that lawn. Don’t get me wrong – he’s a great guy, and always friendly and smiling, and despite the ridiculous language barrier that we both face, I enjoy his company. But stick him in a World’s Final, and he steps up to the plate and plays as hard as he can. Nothing wrong with that in my book. He has my utmost respect as a competitor." |

The "doubt demons” will surely appear to us all, and the player at number 1 in the world can only decline to entertain them, knowing that 2-10 are constantly on the hunt for his title. So he will not succumb to overconfidence, either. Overconfidence may be just as deadly as allowing oneself to be intimidated by an "invincible" player.

Empathy can be consciously channeled

|

| Irresistible distractions like the ones illustrated in this classic painting, can take your mind completely off thoughts of winning and losing. |

Indeed, sympathy and empathy may both be applicable at times, but the empathetic person would be considerate of a partner's or opponent's feelings. Mean-spirited individuals seek to unsettle an opponent by a comment, badgering, interruption or stoppage of play transparently designed to distract or attempt some gamesmanship opportunity for their advantage and the opponent's disadvantage.

Common etiquette in Association Croquet is lacking in some individuals. We should know who those people are before we encounter them in a game; and we should make sure by any means to NEVER have them as a partner. (Sometimes this bad behavior evolves into dementing illnesses, and may only then be seen not to have been deliberate.)

Good judgment, bad judgment

Judgment dictates much of croquet play in the normal course of any game of strategy: when exactly to strike a blow, how to pretend, play a crucial move, read a crosswire, set a leave, corner a ball, or lay a trap. This often is contrary to what your opposition anticipates, and yet it comprises normal good strategy and characterises very good players. Their judgment and the strategic skills required all of the preceding frontal planning features, since what is gained by a preceding move becomes apparent when the innings is regained. Likewise, ploys are made or traps set deliberately to tempt the unwary to violate their own better judgment--to make a risky move which may well be the last shot that player will make at top level on a particular day.

Stress releases hormones (cortisone) and brain neurotransmitters (catecholamines, adrenalin and noradrenalin). This conditions the body physiologically for the so-called "flight and fright" autonomic nervous response. The consequences of this, manifested as excessive nervousness, would affect the timing, rhythm and accuracy of the mallet swing. For example, if the bottom hand holding the mallet tightens involuntarily, the shaft will twist the mallet end and the mallet head will miss the centre of the ball aimed for. Speeding up the back or forward swing similarly risks interrupting accurate timing and momentum of the mallet as it approaches the ball. The end consequence is a missed roquet or hoop.

|

| In his Shakespeare series, John Prince illustrates the well-known terror of the hoop approach. Hoop approaches hold some trepidation for most of us, especially when an enemy ball is nearby. Confidence in running the hoop regardless of imagined consequence must be the ONLY object of mental focus at this instant. |

Most of us during competition play, however, do get excited, and consequently walk faster, think faster, do things like forgetting to stalk or even worse find ourselves thinking about the next six strokes instead of the simple two-yard roquet right in front of us. CLUNK!

In his superb book, Maurice Reckitt advised players to do their thinking while walking between shots, but never to think while playing the shot, instead fixing their concentration on the “blade of grass” where the struck ball is to land.

No hoop is so easy to miss as the one you forget you still have to run in order to win. After the unfortunately and unnecessary CLUNK we are required to walk off smiling, (or trying to anyway) with no dignity left, eternally and unhappily replaying the cock-up in the middle of many, many sleepless nights. That is the needless consequence of a momentary loss of judgment, for whatever reason.

Deception is not the same as "cheating"

I need to make a distinction between clever behavioral deception of an opponent, and cheating.

We all play better some days or some periods than others. What one does to keep a winning edge is to disguise one's poor play, and adopt a more conservative attitude; and when playing well, trust yourself to take a better chanced risk. This aspect of croquet is among the most fascinating aspects of our sport.

Deception by dishonesty is never acceptable. That is cheating, and everyone, especially yourself, will know you're doing it. There is no ‘grey zone’ in croquet. Everything the observer could possibly question, even without a referee watching, should be measured by your most scrupulous judgment. It's not enough that it actually WASN'T cheating; you need to make sure that nobody could possibly declare that it was anything but honest.

Having said this, I’m sure that the vast majority of croquet players I’ve played with or against play Association Croquet with the highest integrity. But let nobody fool you, when you “cheat” you are really cheating yourself.

Reality suggests there are some who cannot remain true to themselves, and their will to win seems to exceed their perfect judgment. Thankfully very few "cheaters" survive without quickly gaining a reputation. You can protect yourself from them by never having them as partners; and when they are opponents, be willing to call a referee on them in every questionable situation.

Avoid displays of temper and anger

When you wiff an easy hoop shot, or whenever you have really let yourself down, why not strike a mallet against a hoop or even throw it over a side hedge? Several reasons: It's dangerous; and such a childish display would encourage an opponent to think “Got you!" What worse thing could you do to your frame of mind? In fact, surely the best thing would be to smile, a bit wryly, perhaps, while walking off after an unforced error or fault, giving the opponent reason to imagine, "He has already forgotten that fault; I'll have to beware in the future."

There are strict laws and disqualification rules related to verbal abuse, language, or inappropriate remonstrations, and so it should be. Australian croquet has in at least three instances banned players for this type of thing, and in my view these regulations should be applied to officials as well.

Terror from past experiences can be a problem, paralyzing you both mentally and physiologically, robbing you of the confidence needed to make progress, and producing the anxiety that will reveal itself in your play,. Anxiety and depression are tight associations.

Don't be ashamed to play at your level. Use the bisques you deserve in handicap competitions! Don't forget that the worst that can happen is to lose a game.

Those who can't or won't surmount the pressures of competition may revert to social play, which is fine, because they may still enjoy Association Croquet without subjecting themselves to serious competitive stresses.

Some will give up croquet entirely, never to play again. It really is up to you and your temperament to how to handle the disappointment of defeat.

Leaving behind negative experiences--be it a bad shot, game, loss, match or tournament--is an ideal which would bear the best positive outcome. Many, however, cannot forget and forgive themselves, and will be stuck with the opposite and counterproductive negative emotions which will continue to affect their play.

The will to win: where does it come from?

I would really like the top Association Croquet players to address this question live one day: "What gives you the will to win?" Secret techniques, simple practice, physical or mental superiority, good genes....what? Perhaps many will make us aware, as Reg Bamford did recently at Surbiton, of the higher cerebral levels of the game. In the talk, Reg called some of his own ideas “loopy,” but I do believe they all represent the finest psychological attributes of the true Croquet champion of today.

In summary, what does one require mentally to win more often? You may be born with sporting genes or come from a sporting pedigree; being introduced into the sport early would clearly help you develop the malleable motor skills of youth effectively. Meaningful practice at every level would certain help assist. But what is most crucial is your mind set. The psychology of play clearly separates the best from the also played, and at the top 10 level or even within your own handicap range, focused concentration in my view is crucial.

How to eliminate distraction, remain calmly focused in every shot, plan between shots, and never let the last poor shot divert you from what you simply know you can do....all of that resides in the brain's frontal cortex. By observing yourself and your mind and temperament in action and in concert with your physical motions, you can practice perfecting that interaction. How determined one is in improving this vital interaction--broadly called “mind control”-- is what makes us successful in competition.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR: James A Temlett is a Clinical Professor of Neurology. Previously he worked at the University of the Witwatersrand Medical School and Johannesburg Hospital (1986 - 2001), spent years in practice in the UK in London and Oxford, and since 2002 has been Professor of Neurology at the University of Adelaide and the Royal Adelaide Hospital in Australia. His research interests are in Movement Disorders (Parkinson's disease, tremors and dystonias), and Cognitive Behaviour (mainly Frontotemporal dementias and non-Alzheimer's dementias).