|

Back to |

| The Front Page |

| Letters & Opinion |

|

Will a world championship for women

improve their standard of play? by Beatrice McGlen and Ailsa Lines layout by Reuben Edwards posted February 27, 2013

|

Many women players in the northern hemisphere countries are stridently egalitarian, rejecting any suggestion of having tournaments at top level separated by gender. On the face of it, dividing the sexes makes no sense in a sport that boasts of offering a level playing field for all competitors, where one sex or the other has no "natural" advantage. So it's puzzling and even ironic that women, overall, fare better in competitions in the southern hemisphere countries that tolerate and even encourage "women only" events. Three women in England noticed these disparities and decided to investigate further by actually playing in the first Women's World Championship in Association Croquet, held last October in Victoria, Australia. They came back with their own attitudes considerably adjusted. Two of them wrote this article, adapted from an earlier publication in the English Croquet Gazette.

One of the unique characteristics of our sport is that men and women can compete on an equal footing and there is a strong body of opinion in the northern hemisphere that women-only events will inevitably lead to men-only events, and so the slide down the slippery slope to a separated sport begins. Attitudes on the other side of the equator are very different, and it was in response to enthusiastic pressure from the southern hemisphere, particularly in Australia, that the World Croquet Federation decided to hold the inaugural Women’s AC World Championship in Melbourne on 21-28th October.

My reaction to the invitation to apply for selection to the 1st Women’s AC World Championship was: "Why would I want to spend all that money travelling to the other side of the world to play in a tournament that could be to the serious detriment of the game?" So, why did I end up playing in Melbourne in October? First, I was rather shocked to find out in May that, despite strong interest from New Zealand and Australia, only one person from the northern hemisphere had entered this inaugural competition. Secondly, Ailsa Lines, a fellow member at Nottingham Croquet Club, was equally embarrassed by the lack of support, so we decided to make enquiries about taking leave from our respective employers and then put our names forward.

Despite the late entry we were both accepted, and on October 20th we arrived at the Victoria Croquet Club in Melbourne to find the most splendid facility--with 12 flat, fast lawns; a huge pavilion complete with showers and a commercial kitchen; floodlighting around the four central lawns; 48 players in the championship; and numerous supporting husbands, partners and family

|

| The 12-court Victoria Croquet Centre, in the suburbs of Melbourne, is one of the largest in the world. |

Team uniforms spark team spirit

|

| The English contingent--Ailsa Lines, Frances Ransom, and Beatrice McGlen--were also the only players in the 48 from the northern hemisphere. They wanted to find out why. |

The first day of play dawned bright and warm. We were divided into eight blocks of 6 so we each played 5 single games in the first two days. The lawns were quick and the hoops required accurate play, so the three-hour time limit for double-banked games meant many games went to time. The bottom two women in each block went into a plate event and the remainder went forward to the knockout. However, several blocks required tie-breakers to determine the qualifiers, which meant play continued under floodlights on the second day until after 10pm (a long day considering play began at 8.30 every morning).

|

| The ability to turn on the lights and extend play in the night is a distinct advantage for some events, including this one. |

The winner was never seriously in doubt, but...

|

| One thing was certain before the event began: Jenny Clarke was going to be the headline. She came to the event ranked more than 100 places higher than any other woman in the 48-place roster. If she had lost, that would have been big news, indeed. In fact, she gave up not a single game throughout. If there's another AC Women's World, it's likely to be held on her home turf, in Christchurch, which would make her a nearly unstoppable favorite. |

So has my view of women’s croquet changed? Unequivocally yes.

The Australian and New Zealand women are competitive but remarkably supportive of each other. Some of the contestants had fairly high handicaps, but they had been encouraged to participate and given the coaching and support of their fellow team members; consequently they nearly all performed above expectation. Talking to many of the ladies, it was apparent that they could not understand the reluctance of female players in the UK to enter the only women’s event remaining in our tournament calendar and were surprised at how few female tournament players we have. Perhaps it is time to have a rethink about this.

What club statistics will tell you about female participation

I did a little research. At Nottingham we have 113 members, of whom 40% are female. When those who are members of the English Croquet Association are analysed, the percentage of women drops to 26%. Looking at all the entrants to the Nottingham AC tournaments, 17% of the contestants in handicap events are women and only 9% in level/advanced. In order to see if this is representative of the total croquet playing community I requested figures from Bowdon, Budleigh Salterton, Cheltenham, Hurlingham and Sussex County, as well as Nottingham-- 6 of the larger clubs in England Those numbers confirmed that the Nottingham figures actually are representative of clubs in the country as a whole, and it is my understanding that the same kind of disparities exist in America as well.

|

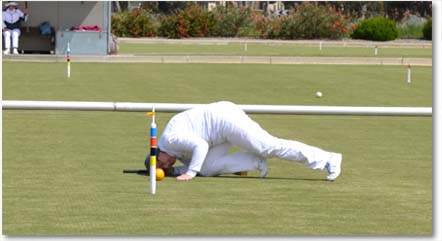

| Ailsa Lines in play. Of the three English women, she advanced farthest in the knock-out, all the way to the quarter-finals stage. |

Many of our advanced non-handicapped tournaments now only have one or two female competitors at best. If we leave things as they are, there is a serious risk that many tournaments will become men-only by default, so perhaps the time has come to make a particular effort to encourage the development of women players before we lose the very feature of croquet we are trying to protect.

Looking for a practical solution

How can we start this process? Clubs are attracting men and women in roughly equal numbers, so the problem is probably not one of recruitment. However, more than twice as many of the men become members of the Croquet Association than women. The Association could investigate why there is this discrepancy, but I suspect that most people join the Association initially because they are interested in playing in tournaments, and the women are not being attracted to tournament play.

|

| Most women seemed to enjoy the socializing in the commodious clubhouse adjacent to the lawns at least as much as the competition on the lawns. |

|

So perhaps clubs should be looking out for their members (both male and female) who are clearly getting the hang of the game and encouraging them to enter club competitions and then handicap tournaments at their home club. Some coaching sessions on the tactics of playing when conceding bisques rather than receiving them would be particularly helpful to the improving player because many people find that transition difficult to overcome. In our club, women in particular seem much more likely to stay in the 16-20 handicap range because they win their games when they have plenty of bisques but lose all their confidence, and their games, without that security blanket and so their handicap just fluctuates.

The second stage is encouraging players to enter tournaments at other clubs, because the experience gained by playing a variety of people in a variety of settings is essential in the learning curve. I have heard many women saying that they do not like going away on their own so they do not enter tournaments at other clubs. It is difficult to know how to overcome this. Maybe it requires two or three women within a club to decide they are going to enter a particular tournament and to arrange travel and accommodation together, or maybe female club members offering accommodation to lone female visitors would help. Once you have been to a club, got familiar with the area and know a few people, the apprehension of going on your own diminishes.

The third step along the development road is playing non-handicapped and advanced tournaments. Women clearly lack the confidence to take this step, particularly if they think they will be the only female playing in a competition. Building confidence is the key, so coaching is important, as is encouraging all club members to enter internal non-handicap competitions whether they are A,B,C or D class. They need experience in playing without bisques; of making leaves; of different openings. Learning from better players helps build that confidence.

More mixed doubles would help

Mixed doubles is a great way to step into the world where the men dominate, and there is always a shortage of women prepared to play. If every club had an internal advanced/level mixed doubles competition, perhaps the men could encourage the women to play and this would then feed through into the tournament scene.

|

| The courtside shelters are good protection from sun and from wind--and perfect for watching the opponents in double-banked games go around the court. |

The final stage is national and international events. In Australia and New Zealand the women have a national, organised structure that supports them. Crucially, the interstate competitions in Australia and the trans-Tasman competitions require teams to contain both men and women, so the development of female players is important at the higher tournament level. Introducing a requirement to have at least one woman in each of the teams in the Inter-Counties in England could have a similar effect.

In the Women’s World Championship both the Australian and New Zealand teams had team uniforms – this instantly gives a feeling of belonging and pride of representation. The two contingents had met up as squads prior to the tournament and received some coaching covering topics such as openings, leaves and one-ball endings. When they arrived at the tournament they already felt part of a team and they provided huge encouragement and support to each other. The English representatives were left entirely to their own devices, and that was quite scary.

This inaugural Women’s World Championship was a really enjoyable event, but for it to be a continuing success it will need much more support from women in the northern hemisphere. For that to happen, fundamental changes in the attitude of women in croquet are required. This is not about turning shrinking violets into strident feminists, but fostering the belief and self-confidence that is apparent in the antipodes so they can blossom north of the equator just as abundantly. Let's hope the debate about the best way to keep men and women playing Association Croquet on an equal footing starts here....

Top 50 women in the world

from the 2013 Croquet Ranking List

| Num | World | Name | Country | DGrade | pdt | Games | Wins | %wins | Last |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 14 | Jenny Clarke | New Zealand | 2443 | -49 | 154 | 128 | 83 | |

| 2 | 73 | Miranda Chapman | Australia | 2204 | -61 | 56 | 28 | 50 | |

| 3 | 86 | Gabrielle Higgins | England | 2169 | 136 | 87 | 45 | 52 | |

| 4 | 110 | Rosemary Graham | Australia | 2110 | 108 | 71 | 50 | 70 | |

| 5 | 128 | Ailsa Lines | England | 2055 | 137 | 58 | 36 | 62 | |

| 6 | 134 | Sue Lea | New Zealand | 2044 | 35 | 48 | 33 | 69 | |

| 7 | 140 | Alison Sharpe | Australia | 2021 | -147 | 103 | 59 | 57 | |

| 8 | 141 | Claire Bassett | Australia | 2016 | -9 | 40 | 27 | 68 | |

| 9 | 150 | Alix Verge | Australia | 2002 | 38 | 54 | 35 | 65 | |

| 10 | 152 | Debbie Cornelius | England | 2001 | -51 | 40 | 17 | 43 | |

| 11 | 155 | Chloe Aberley | Australia | 1992 | 83 | 13 | 10 | 77 | |

| 12 | 161 | Tricia Devlin | Australia | 1980 | -65 | 153 | 89 | 58 | |

| 13 | 167 | Gail Curry | England | 1963 | -28 | 16 | 10 | 63 | |

| 14 | 170 | Nina Mayard-Husson | New Zealand | 1958 | 64 | 35 | 24 | 69 | |

| 15 | 171 | Charlotte Morgan | Australia | 1956 | -68 | 56 | 29 | 52 | |

| 16 | 176 | Margaret Melville | Australia | 1944 | 48 | 77 | 41 | 53 | |

| 17 | 181 | Jocelyn Sutton | Australia | 1936 | -327 | 10 | 6 | 60 | |

| 18 | 187 | Merryl Garrod | Australia | 1927 | 8 | 26 | 15 | 58 | |

| 19 | 215 | Liz Fleming | Australia | 1878 | 103 | 46 | 23 | 50 | |

| 20 | 217 | Alison Robinson | New Zealand | 1876 | -11 | 85 | 43 | 51 | |

| 21 | 218 | Louise Bradforth | England | 1875 | 50 | 49 | 16 | 33 | |

| 22 | 221 | Judy Wembridge | Australia | 1871 | -78 | 26 | 16 | 62 | |

| 23 | 223 | Sue Beattie | Australia | 1870 | -78 | 83 | 57 | 69 | |

| 24 | 229 | Pam Fisher | New Zealand | 1865 | -128 | 20 | 10 | 50 | |

| 25 | 235 | Jannine Hawker | Australia | 1858 | 33 | 81 | 45 | 56 | |

| 26 | 240 | Jane Morrison | Ireland | 1855 | 28 | 48 | 28 | 58 | |

| 27 | 248 | Anna Miller | Australia | 1844 | 70 | 61 | 34 | 56 | |

| 28 | 264 | Wendy Dickson | Australia | 1826 | 284 | 60 | 32 | 53 | |

| 29 | 265 | Kathleen Colclough | Australia | 1825 | 65 | 92 | 50 | 54 | |

| 30 | 292 | Judith Hanekom | South Africa | 1795 | 78 | 10 | 4 | 40 | |

| 31 | 296 | Deidre Hardy | Australia | 1786 | 58 | 38 | 18 | 47 | |

| 32 | 297 | Dallas Cooke | New Zealand | 1783 | 5 | 11 | 7 | 64 | |

| 33 | 304 | Jane McIntyre | New Zealand | 1780 | 16 | 32 | 14 | 44 | |

| 34 | 311 | Lizzie Bassett | Australia | 1775 | -39 | 84 | 44 | 52 | |

| 35 | 316 | Rachel Rowe | England | 1767 | 139 | 20 | 12 | 60 | |

| 36 | 329 | Annabel McDiarmid | England | 1759 | -104 | 10 | 4 | 40 | |

| 37 | 338 | Megan Reynolds | Australia | 1751 | 100 | 57 | 31 | 54 | |

| 38 | 339 | Shirley Carr | Australia | 1744 | -21 | 15 | 8 | 53 | |

| 39 | 341 | Kathie Grant | New Zealand | 1741 | -16 | 85 | 45 | 53 | |

| 40 | 344 | Mary Knapp | England | 1738 | -96 | 41 | 13 | 32 | |

| 41 | 353 | Marion McInnes | New Zealand | 1732 | -60 | 80 | 34 | 43 | |

| 42 | 357 | Laura Whittaker | New Zealand | 1726 | 162 | 29 | 12 | 41 | |

| 43 | 360 | Madeline Hadwin | New Zealand | 1722 | -226 | 10 | 2 | 20 | |

| 44 | 363 | Beatrice McGlen | England | 1720 | -98 | 40 | 15 | 38 | |

| 45 | 371 | Barbara Hooper | Australia | 1712 | -164 | 12 | 7 | 58 | |

| 46 | 374 | Carol Smith | England | 1709 | -71 | 36 | 13 | 36 | |

| 47 | 377 | Alwen Bowker | Wales | 1709 | 90 | 42 | 23 | 55 | |

| 48 | 384 | Liz McLay | New Zealand | 1700 | 81 | 57 | 30 | 53 | |

| 49 | 392 | Elaine Coverdale | Australia | 1695 | 151 | 81 | 50 | 62 | |

| 50 | 397 | Gloria Howell | Australia | 1689 | 11 | 23 | 14 | 61 |

Ailsa Lines is Head of Mathematics at a girls school in Lincolnshire. She has been playing croquet since 1993 and won the Ladies Week (Barlow Bowl) in 1999. In 2012 she won the British Women's Championship and the British Mixed Doubles title. She represented England in the Home Internationals in 2007 and 2008 and has twice reached the group stage of the World AC Championship in 2005 and 2008. Ailsa is a member of Nottingham and Bowdon Croquet Clubs.

Contributors of opinions and photographs include Ailsa Lines, Rosie News, Rosemary Newsham, Keith Aiton, Chris Clarke, Marion McInnes, Chris McGlen, Wendy Betteridge and others. Thanks also to James Death, Klim Seabright, Clive Hayton, John Saxby and Brad Grimmer for providing statistics.