|

Back to |

| The Front Page |

| News & Features |

|

Mallet Mania, a personal journey by Patrick Foy posted January 25, 2016

|

||||||||||

|

||||||||||

If you're an ambitious player, you do what you can to improve your game, and the most obvious place to start is you mallet. Unless you get the best one possible, you'll never know how good a player you really are. The problem is that generally-accepted notions of what is "best" keep changing over time as manufacturers continue to tout new improvements to get their own edge in a competitive marketplace. Here's the story of one player's odyssey through a dozen romances that were great in their time--but only until a more attractive option caught his eye.

|

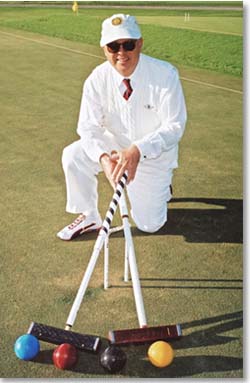

| The writer at Indian Creek Country Club in 2007 with the Ed Roberts 11" all-metal mallet and the John Hobbs 11" Purpleheart wood model. |

And I do mean competitive. There have been reports of startling personality transformations on the court during matches. I have observed supposedly mild-mannered country clubbers go ballistic in a "friendly" non-tournament game. There was a strictly enforced rule at one of my clubs that forbad under any circumstances married couples being partners in doubles games.

Aside from burying oneself in books and videos on strategy ("Bob & Ted") and learning the finer points of the rules, the quickest way to get an edge is equipment, to wit, the mallet. It was the same for me with tennis, which I began playing in the early 1980's. It so happened that my tennis career roughly corresponded to the rapid evolution of the tennis racquet, which has gone from an all-wood, 14-ounce affair at the heavy end, with a small head, to what we have now.

The evolution of racquets and mallets

Today there are no wooden racquets and the weight is generally 10 ounces or less; the head is considerably oversized when compared to the glory days of Rod Laver and Gardnar Mulloy. As a result, I bought nearly 15 different racquets in two decades to keep abreast. And maybe five more as duplicate backups, in case a string broke.

When I discovered croquet, my romance with tennis faded. And it happened all over again: the rapid advances in mallet design has resulted in another buying spree since 1995. Always, looking for that edge.

When I discovered croquet, my romance with tennis faded. And it happened all over again: the rapid advances in mallet design has resulted in another buying spree since 1995. Always, looking for that edge.

The first mallet I treasured was the Jaques' Solomon (designed by the English champion John Solomon) with "Tuftex" faces, a Lignum Vitae head encased with brass ends. I bought an old, beat-up one for $50 and restored it. With only a 9” wooden head, it was quite lively despite its stubby looks. Hickory shaft, weighing in at 3 lbs, 7 oz. Top of the line for Jaques. Amazingly, it can still be bought brand new on their site for the colossal sum of $740.00!

|

| The venerable Solomon from the 1970's, with its signature brass binding. |

As a beginner, I customized the mallet so I would know at a glance which ball was next in rotation. On the brass ends, starting at the top left hand corner, running again clockwise, I engraved the words corresponding to the tape: blue, red, black and yellow.

But the machine-engraved words were too light to stand out. So I stuck blue, red, black and yellow tape on the mallet head, at the foot of the shaft, going in a circle, clockwise. All I had to do was look down to know where I was in the rotation.

Alas, I had to abandon this legendary mallet because I did not feel it was giving me enough punch.

In my mind, the Solomon mallet corresponds to the heavy wooden tennis racquets of the 1960's which survived, but just barely, into the early 1980's. Sticking with tennis for a moment, let me interject that I may have been the first person in America with a wide-body racquet. The wide-body was a significant advancement in the evolution of the tennis racquet, probably the most important in fifty years. I picked it up during a February ski trip to Switzerland in the mid-1980's. When I used it for the first time back in Florida, it was a dream, but I was laughed off the court.

In my mind, the Solomon mallet corresponds to the heavy wooden tennis racquets of the 1960's which survived, but just barely, into the early 1980's. Sticking with tennis for a moment, let me interject that I may have been the first person in America with a wide-body racquet. The wide-body was a significant advancement in the evolution of the tennis racquet, probably the most important in fifty years. I picked it up during a February ski trip to Switzerland in the mid-1980's. When I used it for the first time back in Florida, it was a dream, but I was laughed off the court.

The racquet was the Kuebler "Resonance 50" which was invented by a German engineer named Siegfried Kuebler, who had designed rockets. It was 100% graphite, relatively light and maneuverable despite its oversized head. I had the last laugh. The executives at Wilson recognized a good thing when they saw it. They quickly bought the design and called it the Wilson Profile, which later segued to the Wilson Hammer.

|

| A Wilson racquet from the 1970's compared to the then-revolutionary Kuebler Resonance 50, from 1985. |

The rest is history. The racquet industry was revolutionized. All tennis racquets nowadays are, to one degree or another, wide-body, and most are weighted toward the top and sides. It all goes back to Kuebler.

I believe the croquet mallet has undergone a steady "Kuebler" transformation since 1990. Please note that the importance of weighting the mallet head had already been recognized by Solomon and Jaques. Ergo, the brass ends. But English mallet maker John Hobbs took it to the next level by hiding the weighting inside the mallet head itself, with lead, and making the finished product sleek. Hobbs was my next mallet, an 11" head size. I went on to buy two more at 12". When you pick up a Hobbs, you notice its perfect balance. It's a work of art.

The great thing about Hobbs is that you can design your own mallet, picking out, among other things, what type of wood you want. I made one after-purchase "improvement" to the Hobbs. I asked David Bent, the croquet and tennis pro at the St. Andrew's Country Club in Delray Beach, to switch out the Hobbs' shaft for the stiffer, carbon shaft of Fenwick Elliott. David was using the Fenwick shaft for mallet heads of his own design. The only drawback was, the shaft had to be epoxied permanently into the wonderfully balanced Hobbs head, which arrangement was not so good for traveling.

Concurrently with my Hobbs phase was my discovery of the Ed Roberts mallet. I believe (but could be dead wrong) that the Roberts mallet was the first "all metal" mallet. Ed Roberts has stopped making mallets, but ten years ago it was considered by some top players the best mallet made in America. At some point, the Fenwick Elliott shaft from Australia was added to the Roberts mallet by Roberts himself. It was a perfect combination. I had the 11" version. The current champion of the National Croquet Club, Derek Wassink, still uses the Roberts 11' mallet.

When cosmetics combine with technology

|

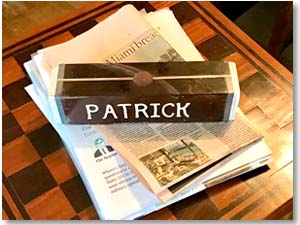

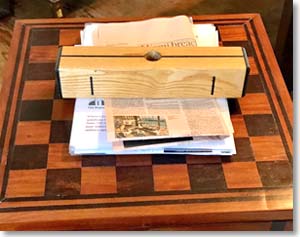

| The Fishstick's nine-inch all-phenolic mallet head converted to a personalized paper weight. |

I eventually bought a 12" Airrow head and, once again, had David Bent attach the Fenwick Elliot shaft to it. Norwich touts the Airrow as, "Quite possibly the best wood mallet in the world!" This could be, although I would imagine that John Hobbs and Bob Morford might have something to say about that. In any case, the Airrow is certainly "a looker". Note, harkening back to Jaques's Solomon, the Airrow sports brass weights on the ends.

|

| The 11" all-wood Oakley Woods mallet head worked well on the court, too. |

Let me count the ways...

The mallet is on the light side, 2 lbs, 14 ounces. It seems as perfectly balanced as the Hobbs, and just as powerful, if not more so. In place of holes on the sides--or in the case of Hobbs, on the underside --almost the entire inside of the revolutionary "Hoop Maker" is gone. You can see right through it. That is nice, because you can be sure it will not be affected by a strong breeze.

More importantly, a proprietary formula of aluminum and two alloys, combined with overall balance using CAD or computer-aided design, somehow allows you to hit the ball more softly than you normally would. But the engineering is not based on peripheral weighting, as you might think at first glance.

|

| The PFC Hoop Maker in 2017. |

What's the secret? I don't know, but it involves redirecting the force created when the mallet hits the ball and returning this impact vibration from the central percussion chamber, directly underneath the shaft, back to the striking face. It's shock wave transfer. There is no peripheral weighting of the mallet.

With respect to "shock transfer" it reminds me of the Keubler. "Resonanz" in German means resonance, feedback and response. On my original Keubler 50 there is a little diagram in German showing how the wide-body design of the racquet makes the tennis ball fly off the racquet with no deviation and hence very little loss of power. It's solely the design, not the weighting, doing the work.

In sum, the "Hoop Maker" generates considerable punch with seemingly less effort and less stress on one's body. And it is accurate. No question about that. Of course, certain days it is more accurate than others. It depends as well on what you had for breakfast that morning. Will it be everyone's cup of tea? No, of course not. Is it the final word, the final iteration of mallet design? For my sake, I hope so.

Patrick Foy grew up and resides in Miami Beach, Florida. He is a photographer, writer and real estate broker. He is a graduate of Columbia University and of the Canterbury School in New Milford, Connecticut. He started playing croquet at Indian Creek Country Club in 1993 when Ted Prentis was the pro. He used to write a monthly column entitled CHATTER for Garth Eliassen’s now-defunct, on-paper publication, The National Croquet Calendar. He remains an occasional tennis player, and drives to Palm Beach on the weekends to play croquet at the National Croquet Center.