|

Back to |

| The Front Page |

| People |

|

"Bad Boy" Mehas succumbs to brain tumor |

||||||||||||||||

|

by Bob Alman with remembrances from many others Posted July 18, 2009

|

||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||

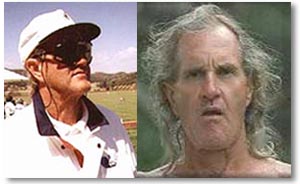

Mik Mehas died in Ventura, California Sunday at the age of 68 following surgury on June 16th for removal of a brain tumor. He was being cared for at the home of his son and former wife in Ventura, California. "Bad Boy" Mehas carved a unique place for himself in the sport of croquet, beginning with his entry into the top rank of players in the early nineties, winning multiple national championships in both "Association" and American Rules, as well as Golf Croquet. At his peak, in the late nineties, he could be counted on to be a finalist in just about any event he entered in America.

|

The manner of his death - the brain tumor - only adds to this mystery. Could a shift in brain chemistry from a tumor growing for any number of years account for the oh-so-distinctive Mehas personality?

The early reports of a brain tumor - diagnosed 20 months ago, in late 2007 - were at first discounted by many Mehas observers as a fabrication to explain or excuse behaviors which had often resulted in official grievances being filed with the US Croquet Association or other organizations, followed by suspension of privileges. Mehas was banned from many croquet clubs for many different cited reasons - among them the best clubs on the continent: Beverly Hills, Mission Hills, Sonoma-Cutrer, and most recently, the National Croquet Club in West Palm Beach, where Mehas lived for a great part of the last four years of his life.

In 1998, Mik Mehas was at his peak, both in competitive play and in arousing the ire of the croquet establishment. Now, more than 10 years later, in marking his passing I can do no better than quote myself in an article written that year, under the subhead of "The dark legend of Mik Mehas."

In the short history of USCA croquet, several personal legends have emerged, all of them benign - until Mik Mehas. First there was the legend of a country bumpkin in overalls and a pickup truck rolling into Palm Beach and confounding the socialite glitterati with his expert play; then there was the legend of the tiny wunderkind from the Southernwestern desert who, with his similarly scaled-down mallet, took on the champions and beat them at their own game. (...Archie Burchfield of Stamping Ground, Kentucky; and Jacques Fournier, of Phoenix, Arizona.)

But the legend of Mehas has shaped itself in darker, ominous tones. For some, it is simply about a figure of irrepressible vulgarity. For others, the subject is deliberately evil, forever unrepentent and unredeemable. Many believe that such a presence can poison the image of the croquet establishment as it sees itself and wishes to be seen by the world.

Most opinion falls out broadly in two camps: One side seems convinced that Mik Mehas is a hopeless case, that his association in any way with USCA croquet is bad for the sport. As one respected figure who declines to be identified said, "He is a bad man. He is bad for croquet. Something needs to be done about it." On this side of the issue, facts of particular grievances are beside the point. The ultimate truth of the issue, for these hard-liners, is that the corrupting influence of Mehas should be excised from the body of USCA croquet.

The other side can be represented by a member of the Management Committee (also asking not to be identified) who sighs wearily and declares with more than a hint of disgust: "This is a waste of time! This is a non-issue! Instead of spending all this energy trying to get rid of one USCA member, we should be working on getting 10,000 more people into the USCA!

Whatever decision is taken by the Management Committee on team selections, one thing is certain: The dark legend of Mik Mehas has already colored the image of America's most elegant sport - a sport that in coming of age learns to accommodate more than one single, iconographic image, style, and personality. If Mehas did not exist, he would have to be invented, and he is being constantly invented and reinvented. The legend of Mik Mehas...may bear little resemblance to the man, and it is beyond his or anyone's control.

Branding the "Bad Boy"

It occurred to me, in reporting all this tumult, that if Mehas had a press agent, he would use the hubbub to brand his product, and this I did, putting into print Mehas' "Bad Boy" tag, in a 1997 article reporting on the several grievances against him. When he saw me later at an event, he acknowledged, in his way, that I had done him a favor by giving him that particular spin. What he actually said was, "I don't know whether to kill you or kiss you." Knowing very well that Mehas wasn't going away, my intention was simply to attach to him a snappy label that the mainstream press would pick up and use, to the benefit of the sport. (Rhys Thomas has told me that he used the "Bad Boy" label in a press release years earlier to promote an international event at Sherwood Country Club in Southern California.)

|

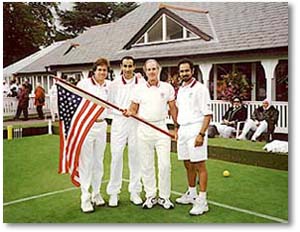

| The American team at the 1998 Golf Croquet World Championship: Jim Houser, Sherif Abdelwahab, Mik Mehas (carrying the flag) and Ihab Abdelwahab. |

It was, possibly, his greatest moment, even as he continued to surround himself with controversy.

Mehas seems to have made croquet his principal occupation for the last 20 years of his life, and during all that time he gave the impression of living a hand-to-mouth existence. There were reports of pyramid schemes and insurance payments from a number of automobile incidents. Friends around the country - including an impressive succession of girlfriends - were always there to put him up and make his life easier.

|

| The caption for this picture in the 1997 Croquet World Online story said, "Michael Mehas of Palm Springs, Calfiornia, carries the American flag at the opening ceremonies, along with darkhorse hopes for an American breakthrough in the third Golf Croquet World Championship." |

Mehas himself had been coached, early on, by the (almost) equally colorful CB Smith of Southern California, renowned as a champion of Roque and the charmingly irritating old guy who showed up at the tournament in a small van plastered with bumper stickers, which he parked courtside (when allowed) and used as his hotel room.

Encouraged by CB's mentoring, as Mehas entered the ranks of top players in the early 90's, it was clear that he was not going to achieve celebrity as a "lovable eccentric" or anything of the sort - not in the croquet world. To the Palm Beach elite, his style was more vulgar than sporty, and his penchant for stirring controversy did not endear him to the establishment. He ignited disputes with some of the most prominent people in the croquet world, again and again and again. After a time, it seemed to me that Mehas' legendary contentiousness swung the "vote" against him as much as the facts of whatever case he was defending - whether it was before a grievance committee of some kind or in the consensus of courtside gossip.

Moreover, I believe that at least some of the accusations against him were put forward by disapproving people who grasped an opportunity to make a case against Mehas, when the same incident or circumstances would not have generated that kind of heat had some other person been involved.

A matter of style

|

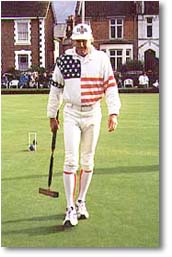

| Mehas just short of over-dressed in his characteristic garb for the finals of the 1998 Golf Croquet World Championship at Leamington Spa in England. |

I will not catalog here the many controversies Mehas was accused of fomenting. (Some you can read about in the RELATED LINKS at the top of this article.) Most of the "evidence" in these cases is of the "he-said, he-said" variety, weighted from the beginning by Mik's reputation. I can comment, however, on one occasion when I couldn't resist asking him the two questions: "Did you really do that?" and "What were you thinking?"

I asked if he had really put his fist through the wall of a Senior Center in Southern California where he was doing a croquet program, and without giving me a chance to ask the second question, he said, "Would you rather I hit that old biddy in the face?" It was classic Mehas logic. "If that's the only choice, I guess the wall is better," I conceded.

Sometimes he was wrong, hands down

Mehas made my life more difficult than it needed to be in the period of chaos that followed the stroke and consequent disability of Chuck Steuber, founder and financer of the National Croquet Center, when I was organizing the Center, building the club, managing the facility, and hosting events. There was no USCA Golf Croquet Committee to negotiate with the WCF for securing the 2002 Golf Croquet World Championship, so on the agreement of Steuber and the outgoing president of the USCA at the time, WCF president Tony Hall and I had made a number of "agreements to agree," with the expectation that whatever committee was eventually appointed would abide by the agreement - especially as the USCA was not charged with funding the event, which I saw as a promotion for the new Center.

|

| Accepting the applause at the trophy presentation at the 1998 Golf Croquet World Championship are Mehas in the middle, flanked by winner Younis of Egypt, and third place Newell of Ireland. |

This was at a time (following Nine-Eleven) when international relations were already chancy, and Mehas had broadcast a long diatribe aimed at the Egyptian Croquet Association implying, among other things, that the pyramids were in the wrong place and that the revered president of that organization was a crook. At some point I was advised, confidentially, that the Egyptians had been waiting for the new president of the USCA to contact them to disavow the contents of the letter and assure them they would be fairly treated at the championship, but no such contact was made. Therefore, with Director of Croquet Archie Peck's agreement, I composed a letter from us jointly to the president of the Egyptian association promising that the USCA Golf Croquet Committee would have no authority to affect the outcome of the championship, and that bad conduct from any party in the event would result in expulsion. So the Egyptians came to the championship in force and took another title, as expected.

|

| California's Mik Mehas - watched here by Arizona's Fournier brothers - was the only player to win all six singles games. The three are on the six-man United States team for the MacRobertson 2000 matches in New Zealand, croquet's premier international team event. |

In fact, the bad motives ascribed to many Mehas' actions were doubtless false in many cases, including the matter, just last year, of the WCF Golf Croquet World Championship. When he was not granted an official USCA place, despite his playing record, he informed the selectors that he would go to South Africa anyway and win a place through the Qualifier Tournament. In response, all the selected team decided not to go to South Africa, in protest. Mehas didn't show up, either, which meant that the US was not represented in this major event. The explanation, at the time, was Mehas malice. Now, in hindsight, it's easy to see that complications of a brain tumor could be the more immediate cause.

Giving croquet a sporty image

Mehas was tailor-made to give the image of American croquet a richer texture, something that played well against both the "Palm Beach" and "backyard croquet" extremes - a third alternative that suggested stongly that croquet is a sport, rather than a lifestyle. Of course the Palm Beach establishment feared and loathed him. One of them told me recently how pleased he was to qualify for a high-level tournament at the National Croquet Center, with the only downside being that he would have to play against Mehas. (I told him that Mehas had established a pattern of registering for tournaments and not showing up - which proved to be the case this time, as well.)

|

| This ceramic medallion, supposedly showing a generic version of "croquet player," reproduced in the hundreds at the National Croquet Center, is actually a representation of one player: Mik Mehas. |

Photo editors often never knew they were dealing with an exceptional figure; no one else looked as sporty as Mehas. When I engaged a ceramic artist eight or nine years ago to create hundred of medallions I could use as prizes and trophies for events at the National Croquet Center, I showed her hundreds of photos of croquet players to help her create the right icon. When she showed me the image she came up with, I laughed and said, "It's great, but you can't use it. Everybody will know it's Mik Mehas!" So she modified it slightly, but it still came out looking like Mik Mehas.

Recalling the glory years: the 90's

The 90's were definitely Mehas' best years in croquet, beginning with his first significant win in 1990 at the Southwest Regional, in both singles and doubles (with Rory Kelly). Mehas once told me that his goal was to win every tournament he entered once - when he did that, he could concentrate on another event, be it a titled tournament or a prestigious invitational or open. (He reached the finals of the San Francisco Open three times consecutively in the mid-nineties, winning on the final try.)

He was the national champion of both USCA American Rules and International Rules for two years running, in both 1997 and 1998; and he achieved the highest finish of any American ever in the WCF Golf Croquet World Championship in 1998 as the runner-up, to the utter amazement of many - including the Egyptians, who had never seen such "non-Egyptian" strategy deployed with such success. In 1997, he won the Grand Prix and was therefore USCA "Player of the Year."

Although his success rate was not as impressive after the nineties, he still had more than his share of trophies, taking the USCA Golf Croquet National Championship in 2004, and winning the USCA Seniors Championship in two consecutive years - 2007 and 2008 - after he had received the brain cancer diagnosis.

|

| Mehas dressed as a gentleman at the croquet ball in the National Croquet Center, with Elizabeth Galle. |

I have heard reports that Mehas showed an exceptional swagger on showing up at the National Croquet Center for those titled events, despite being denied membership in the members' club. I never witnessed this and discounted these reports. In fact, Mehas was obliged to be exceptionally careful about his behavior at those events, because the organizers, in many cases, would have been happy to throw him out.

But he's gone now, and the Palm Beach establishment doesn't have to worry any more about Mehas showing up on the court. But it's my bet that for many years to come, players around those courts, at idle moments, will continue to tell stories about croquet's one and only Bad Boy. Some of those stories follow, from people we invited to comment on Mik's passing.

|

REMEMBERING CROQUET'S "BAD BOY"

Many people were invited to send remembrances, and most of the messages we received are published below, in slightly edited form. The editor invites additional comment, which may possibly be added at the end.

|

|

I will miss Mik. He was always friendly to me and my wife Anne, and we had some fun times at the various tournaments we played in. He was an excellent competitor. His presence on the Shield team that went to NZ was essential for the USA team to win a test match for the first time. He also added some drama to the game of Croquet. But frankly, it was the others that didn't want to be in a tournament that he was in, or didn't want him to go to a particular tournament that added the drama. I found that in all the Mik Mehas Situations, the accusers were just as bad as what they were accusing Mik of. Whether it was their lame proof, or their overreaction to Mik's alleged injustice, or their refusal to participate in a tournament because Mik was going to it, or their refusal to invite or select Mik to a tournament, their behavior was just as bad or worse than his alleged bad behavior.

- John Taves, former national champion and USCA International Team member |

|

The Bad Boy's son Michael has been one or my dearest friends for 30 years. At one time in my life my whole world was that amazing whirlwind of life on Woodrow Wilson Drive between the Cassavetes house and the Mehas house - my two favorite places on the planet. I still feel the energy of those days when I drive down that street. Mik was a very colorful guy, a world class athlete, and the last sport he chose to excel in (there were many) was croquet. It has been written of him [by Bob Alman in 1997] "He seems incapable of following the social code, but on the court he has achieved a mastery of the sport equaled by few. Mik Mehas will inevitably continue to be a powerful presence in American croquet. He may never win a charm school award or be elected to the Croquet Hall of Fame. But for a long time, and repeatedly, he has tested the limits of the American croquet establishment, which, for many, is the embodiment of a genteel way of life, and only secondarily a sport. Though incapable of following the social code, on the court he achieved a mastery of the sport equaled by few. Basketball has its Dennis Rodman. Like it or not, American croquet has Mik Mehas."

- Chris Kinkade, a lifelong friend of the Mehas family |

|

When I went to my first tournament in 1990, Mik Mehas and Rhys Thomas were the two people who went out of their way to help me learn the game. They made croquet interesting and fun from the start, and helped create an enthusiasm for the game that I hope I never lose. Although Mik was a very competitive person, he never hesitated to give helpful advice (usually after beating me! ), and I will always be grateful to him for pushing me to become a better player. Over the years I spent a lot of time and effort defending Mik, and a fair amount of time pissed off at him. But despite his uncanny ability to create controversy, I enjoyed his company and found that a tournament with Mik in it was always more interesting than a tournament without him. I considered him a friend, and I will miss him.

- Doug Grimsley, USCA Player of the Year, winner of the Croquet Grand Prix |

|

I first met Mik in the late 80s at a tournament in Georgia. He was enthusiastic and affable. He was very talented in the sport but sadly he developed some human relationship challenges preventing him from being accepted favorably in our small croquet family. I think we have a lot to learn from Mik's approach - that is, let your mallet do your talking to get good results, rather than stirring controversy on and off the lawn. In the final analysis: He loved the game and I am sorry he has passed!

- Bob Kroeger, Croquet Pro |

|

Mik was certainly larger than life; a Damon Runyonesque character. He was the first accomplished player I met when starting croquet in 1996. I learned much about croquet from him (jn 1997 he was Player of the Year). He was most generous with his time, lessons, advice and introductions to other seasoned and championship players. In turn, we extended our hospitality for housing, dinners and introduction to ladies who might find his considerable skills charming. On the other hand, Mik would brook no challenge to either his style, skills, advice or on-field calls. His fiery, confrontational rebukes often earned him much approbation and enemies for life. Mik was his own man, marching to a different drummer than most - elitist but confrontational. Yet most will grudgingly admit to his sensational playing skills.

While often clothed in leather jacket and jeans, I was most amused not long ago to see that a young lady friend had managed to round off his rough edges and dress him in Palm Beach pink or green polo shirts and khaki trousers - the rough diamond had been buffed and polished at least once. Mik fought his disease with characteristic vigor and grace. I consider him a most difficult but admired friend. Mik was Mik. The members at Palm Beach Polo enjoyed the croquet lessons received from Mik, but he also greatly exacerbated the owner, which contributed to the demise of croquet at that once-prestigious club. He will be missed - not without a few shakes of the head and a wry smile. Mik was Mik - he made his own luck, both good and bad. He will be remembered. - Gary Weltner, president, Croquet Foundation of America |

|

My favorite Mik story is when I was picked for the 98 Solomon Team.

I had made it through the back door so to speak because so many other players (Stark, Taves, Rodoni, etc) had made themselves unavailable. There was some debate as to who would be the captain of the team since we were a rather inexperienced bunch. Eventually it was decided that Erv Peterson would accompany us as a non-playing captain.

Prior to that decision, or at least prior to Mik being aware of it, I received a call from him early one morning at home. This was strange to me since I had never spoken to Mik anywhere except at a croquet court. He congratulated me for my selection and we exchanged pleasantries for a bit. He then moved on to the purpose of his call. He was lobbying to be named captain of the team. Of course he never came out and said he wanted to be captain of the team, he just listed all the reasons why other people shouldn't be captain. Three of us had never played on a US Team before. Of the three who had, one had no interest in being captain, and as Mik put it, the other one would probably be drunk the entire trip. What really cracked me up was that during his non-pitch pitch of himself, he stated over and over that with the weak team we were sending, we had absolutely no chance of winning the test! "Really," I thought to myself, "you want me to support you for captain and the best way to convince me is by telling me that because I'm on the team (I played in the lowest ranked spot at #6) we have no chance of winning? Is that really your pitch?" Of course I didn't hold it against him, I knew it was just Mik's way of saying the absolutely wrong thing without realizing it. And I did achieve some measure of satisfaction in England. I won one of my singles matches and my partner and I defeated the number 1 doubles team from England. - Jim Audas, member of the USCA '98 Solomon Team |

|

Mik Mehas was happy with "The Bad Boy" image and in later years seemed to be happiest pushing the buttons of committees and administration to see how far he could go to offend. In his normal-person mode he had a great sense of humor and easily got you laughing, but when that person disappeared it was best to distance yourself from him.

We had good times, bad times, fun times, argumentative times and a lot of pain-in- the-butt times. Above all these quirks he established himself as an always-to-be- reckoned-with croquet player, winning many national titles and major events in all versions of croquet. A major pain to many players was his "out game" strategy in American Rules croquet. He truly tested the patience of the players on and off the courts. His Bad Boy image was his "badge of honor" and in many, many ways will be missed. Though many of us tried to miss him as long and often as possible, if he wanted to find you he did, and did a better job than the government tracking you down. If he called you and had something to say and he had to leave you a message, it was then he was at his worst. It cannot be denied that Mik was Mik. - Len J.Canavan,Chairman, USCA Golf Croquet Committee |

|

I met a gentle and spiritual side to Mik after he'd beaten me in a final in Phoenix. He told me to try and get out into the desert, where I could truly get in touch with my soul. I like that memory of Mik. I never had a cross word with him.

- anonymous by request |

|

I played more of my tournament games against Mik than anyone, and we always had challenging and exciting games. In the late 1990s, he joined the Arizona Croquet Club and made many visits to Phoenix for tournaments and practice. My game benefited greatly from his competition. Off the court, he was a good friend, though I have not seen him for several years. In September 2008, he informed me that he was diagnosed with a brain tumor in January and was feeling better. In late March 2009 he still had plans to play in the North American Open in May. Three months ago we talked over the phone and he did not bring up his illness. I was surprised and saddened to hear that he has passed away.

- Jacques Fournier, winner of the Sonoma-Cutrer World Championship at the age of 17 |

|

Mik was obviously one of the best American croquet players of the modern era. Unfortunately, his demeanor on the court usually never matched his ability. In the long run, he paid dearly for his behavior by not being selected to international teams.

In my view many of Mik's shortcomings stemmed from always trying to push the envelope as far as he could, which was often times too far. However, Mik loved the sport of croquet and was keen on seeing it grow. He often suggested to me good ideas for increasing the exposure of croquet. He introduced many new players to the game and was willing to take the time to teach them and give them tips on how to play a particular shot. To paraphrase Woody Guthrie, as through this life you wander you meet some interesting people. That has certainly been my experience in croquet. I'm glad to have crossed paths with Mik. He was a challenge at times, both on and off the court, but I am going to miss him. - Rich Curtis, former president, United States Croquet Association |

|

Mik Mehas was very bright, a brilliant strategist, a great athlete, and an astoundingly good player in his prime. I will always remember him fondly.

At the same time I completely understand why so many people disliked him intensely. He loved to defy convention and authority. He seemed to thrive on controversy and confrontation. He was sometimes competitive to the point of unsportsmanlike conduct. In addition, I saw, firsthand, behavior that made me cringe on many occasions – rude or sexist remarks, foul language, and combative or threatening behavior. His actions and behavior created strong feelings in those wronged – and deservedly so. I didn’t and don’t excuse or support those behaviors. It drove me crazy to see him behave in these clearly self-destructive ways, though he directed none of them towards me. We will never know if his tumor, which I was told could have developed over many years and was in the region of the brain that controlled personality, had anything to do with his low-flash-point anger or other aberrant behavior. I like to think that was the case, but I doubt his detractors do. My belief is that one would not logically behave the way that he did, on occasion, unless there was something seriously amiss. Why will I remember him fondly? He was one of my first teachers, and continued in that role until just before his operation. He was always extremely patient with me and very generous with his time. God knows I tried his patience many times. I was not the swiftest of learners, but he hung in there, and generally controlled his exasperation. He loved to teach anyone who was truly interested in playing the game and getting better, and I fit that mold. It was extremely difficult for Mik to see someone trying to learn the game without stopping to tell them how they could have played a shot better. Unfortunately, he often told them whether they wanted to hear it or not – or whether they were playing a game in a tournament or not! Mik was somewhat paranoid – but many people WERE out to get him. Those people may be happy he is no longer with us. But this game, played in white and noted for its characters, just lost the most colorful and exasperating character in the sport. I will miss him. - David McCoy, Director, Croquet Foundation America |

|

My father came out from Florida to California on May 14 because he’d had major swelling in the brain. That nasty glioblastoma multiforme was acting up, and Dad was on his way out, but we just didn’t know it at the time. He’d been first diagnosed back in January ’08 and was given 30 days to live back then. It ruined my dad’s trip to South Africa for the croquet championships, but Pops had an important decision to make, and he’d made the right one. He'd to stay and battle this new life situation, which turned out to be the beginning of the greatest transformation these senses ever witnessed. My father bore down with exploring all the alternatives to traditional treatment. He probably tried them all, some of which seemed to help, and he pushed hard toward recovery.

The “Bad Boy of Croquet” was getting beaten up pretty badly by the toughest foe he’d ever encountered, and he was suffering as a result. Disorientation set in as did the nasty side effects of the steroids. So we went to work right away. Our first stop was with the incredible neuro oncologist Dr. Timothy Cloughesy at UCLA, who reiterated the need for immediate surgery. When my dad was returned to his hospital suite the day after surgery the reality that the battle had just really begun started to set in. The easy part was over, and the serious stuff was about to begin. We needed to immediately battle this grade 4 cancerous residue that had spread from my father’s right frontal lobe to the left. In a week’s time, Dad would begin an aggressive campaign of chemotherapy, 42 straight daily doses, and radiation for six weeks. Dad wanted to continue the alternative supplementation to his therapy that he thought might give him a chance. I’m not sure he had ever totally realized how grave his situation was, but my personal denial was beginning to wither away. I was starting to realize that my time with my father would be limited. This Super Man in my life was subconsciously preparing his bed for checking out for good. During my father’s three weeks of intense therapy, we both experienced amazing personal transformation. The things that seemed so important only days or weeks before really meant nothing anymore. My father and I began to put things in their proper order. Fifty years of wasting each other’s time had come to an end. I worked hard with my father, and pushed him in his new regimen. We didn’t have time to waste; all we had, at all times, was right now. Each moment was precious, and many were very difficult. I fell off my father’s oak tree. I was as difficult to deal with as was he. Yet, the façade of ego had begun to melt away, on both ends. There came a time for mutual admiration and respect that had never been there in either of our lifetimes. My father taught me the virtues of wheatgrass juice twice a day, and vegetable juicing twice a day. He introduced me more deeply to the virtues of tai chi and qi gong. My girlfriend introduced us to her family’s chi practitioner, and my father – and I – were introduced deeper into the reality of chi flow through the physical body. We did exercises three times daily to rid the body of negative chi, and then each day after chemo and radiation, on our way back to Ventura (these grueling daily five-hour trips did take their toll) we would stop at my alma mater, Pepperdine in Malibu, California, and work on an exercise to fill the body with energy from the sun and earth, and using the earth to help suck the negative chi out of the body. And you know what? This stuff was beginning to help. I don’t know how much it helped my father in the overall scope of things, but he would always say that the time at Pepperdine was his favorite part of every day. I never missed a day of taking my dad to LA for his treatment. But the joy I experienced in my physical transformation dissolved in the midst of witnessing the quick deterioration of this incredible Human Being I’d come to learn to love like no other. Dad was suffering all sorts of indignities as his body began to fade. It was difficult for my father emotionally, and I still rode the denial train believing that we would have some more time together, to do things like we used to, to do things the right way. Pops wanted to be the poster boy for this nasty kind of fight he was in, but it didn’t turn out that way. But some things are amazing in other ways, and so was this process. On that last day, this past Saturday night, I witnessed the total surrender to all that is by my father. I saw and heard and felt him settle into his ultimate destiny. It was only a week and a half ago when Dad told me of his meditation where he’d asked God to tell him what his mission was. I may not have been sure of it at the time, but I know now what it was. My father’s mission was to change the lives of those closest to him, and he accomplished this in an amazing way. By dying my father saved my life. I’m a much healthier person now, who no longer suffers from migraines, and my life’s purpose has been dramatically altered in a very positive way. And something else completely amazing took place. During these last two months together, my father and I learned to love, respect, and admire each other. My father was an incredible person who I really never gave myself the chance to know. He was a tough sell, there’s no question about that. But when the mask of the ego was removed, the remaining Being was filled with so much compassion and so much of that all-important high-vibration we call love. My father was an amazing individual who not a lot of people really understood. But if they ever got the chance, they would find an incredible spirit who possessed a vibrant feel for life. For myself, I’m a much greater person for having found this out. - Michael Mehas, son of Mik |