|

Back to |

| The Front Page |

| People |

|

The Amazing CB Smith

|

||||||||||

|

by Rhys Thomas layout by Reuben Edwards Posted May 19, 2012 Re-Posted May 8, 2020

|

||||||||||

|

||||||||||

C.B. Smith, one of the most colorful croquet players in American history, passed away at his beloved home in Santa Monica, California on Wednesday morning, May 6, 2020. He was 97 years old. To those who knew him, he was the epitome of a true character with a pure heart of gold. On the court, he was a great competitor and gambler who always wanted to have some kind of bet on the game--usually a beer. Off the court, he was a generous friend and mentor, humble to a fault, who loved sharing his knowledge and experience. The following tribute was written in 2012, a few years after C.B. finally hung up his distinctive short-handled mallet and "retired" from croquet. C.B. had five children, 10 grand children, 13 great-grand children, and 2 great-great grand children. He is survived by his loving wife, Naniek.

- Rhys Thomas

American croquet can boast several well-known characters who have enlivened competition on the court and added dimension to a sport usually characterized in American media as an elegant pursuit of the wealthy class. The early against-the-grain exploits of Kentucky farmer Archie Burchfield and later the deeds of the inimitable Mik Mehas were celebrated in the press and helped to balance the sport’s public image. CB Smith’s reputation was less publicized, but well known within the sport. For many—especially those of us promoting croquet on public courts—CB represented the possibility of the organized sport going mainstream. For others, both his on-court and off-court behavior was anathema. But for everyone who saw him in action in his prime, CB was an unforgettable one-man spectacle.

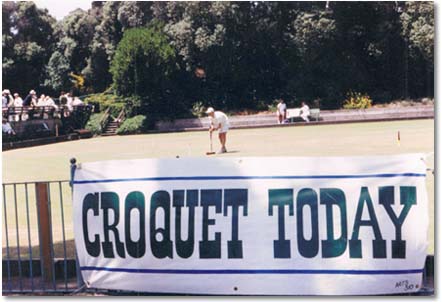

English legend John Solomon thought he'd seen everything in Croquet…and then he played CB Smith in the San Francisco Open. It was a cool, foggy morning in May, 1995. Wayne Rodoni had scheduled the game on the bowling greens of Golden Gate Park as a mini-feature of the tournament: England's great statesman of the sport versus America's wily senior citizen.

|

| The San Francisco Open in the early to mid 90's attracted more top-ranked players than the USCA nationals. With competition worth beating and within driving distance of his camper, it was CB Smith's favorite event. |

I'd met John several years earlier in England and before the game I said to him, "You're in for a real treat playing CB." He laughed at the thought and politely shrugged it off. After 60 years of croquet, the 73-year-old champion really had seen almost everything. But he hadn't seen CB, perhaps the most colorful character in modern American croquet history.

|

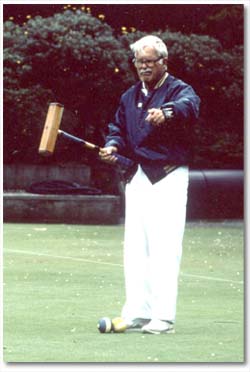

| CB Smith shows his "Big One" to John Solomon. Rhys Thomas photo. |

|

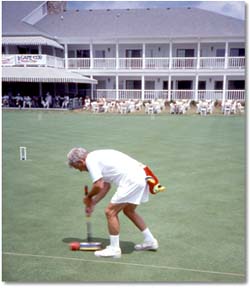

| CB at the Georgia Masters with his parrot. Sheila Slimbarski photo. |

The game began typically enough—for CB. He didn't come into the game with Yellow. CB loved playing the "out game," which meant withholding a ball from entering the game with full life by passing through the first hoop and becoming eligible for roquet and croquet. Sometimes he'd keep both balls out and chase you around the court with one of them, trying to occupy your space on the lawn so he could place your ball one yard north of Hoop 1, taking full advantage of a peculiar loophole in the official American Rules of the day. This time, he kept Yellow out and let John have a free go at #2. The trap worked when John broke down. Now CB had his audience, and John had his show.

|

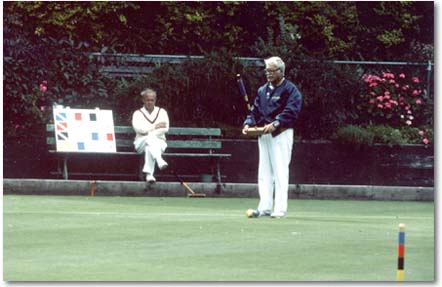

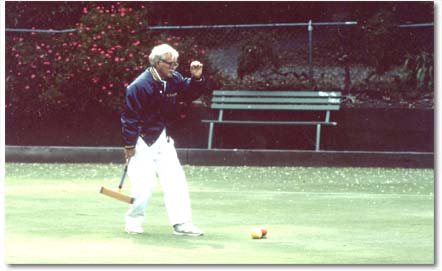

| Measuring a shot with the "Plumb Line" at the 1995 San Francisco Open. Rhys Thomas photo. |

|

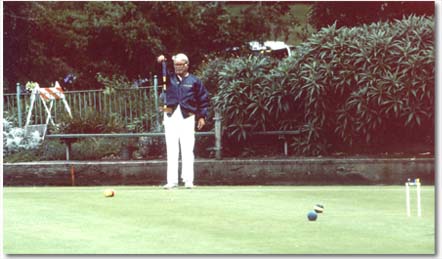

| CB brings out the "Six-Shooter" at the 1995 SF Open. Rhys Thomas photo. |

To measure a croquet shot, CB will break out the "Six-Shooter," aiming with his hand fixed like a pistol, pointing that-a-way for this ball and this-a-way for that ball. Pop-pop.

For a long take-off, CB brings out the "Big One" to measure the angle. And then the peanut gallery goes wild with anticipation, knowing what's coming next. It's CB's signature move. "Up Periscope!" Index fingertip to thumbtip, right around the eyeball, spying his long range target. Load torpedo tube one, and fire! The old submariner still has his eye on the target.

|

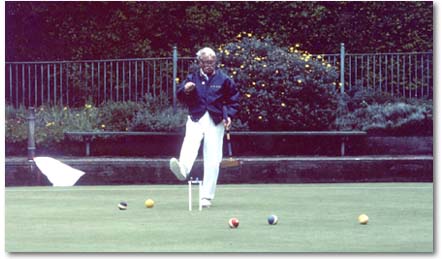

| "Up Periscope!" Rhy Thomas photo. |

The great John Solomon could only chuckle in amazement as he watched his eccentric adversary work all his moves, the balls, and the clock for a 13-12 victory in the San Francisco fog. For CB, it was the perfect kind a game—"a pitcher's duel," he'd cackle. And that's a cackle unlike any other, unmistakable and unforgettable. If you heard it once, you'd recognize it forever and know that the inimitable, unsinkable CB Smith is nearby.

|

| "Got it!" Rhys Thomas photo. |

After the game, John came up to me and said "You were right. In all my years I've never seen anyone like CB." The next day, John brought out his video camera to record some of CB's moves for those at home who otherwise might never believe what he'd seen. For those of us lucky enough to know and play CB day-in, day-out, year to year, around the country, every experience was a new, unique treat.

Novice training by CB Smith

I first met CB in April, 1988, when I joined the Beverly Hills Croquet Club. Dave Collins was president at the time and gave me my introduction to the happy-go-lucky retiree who would become my croquet teacher, tournament mentor and great friend. I was crazy for the game and over the next three years, CB would teach me to become a world-class croquet player.

CB was an excellent croquet teacher because he was a devoted student of the game. He watched all the great players of the day—Neil Spooner, Reid Fleming, Stephen Mulliner, Archie Burchfield, John Osborn—and he brought lessons home to Beverly Hills. "Neil did this at Arizona," he'd say, and he'd show me the "route,"" or "croquet-out." "Reid did this at the Regionals" and he'd show me how the master of American Rules tactics stymied his opponent by taking full advantage of rotation and deadness.

|

| CB and Neil Spooner at the 1985 Sonoma-Cutrer World Croquet Championship. Neil Spooner photo. |

CB didn't just bring lessons to the court; he also brought great players. Colleen and Tony Stephens of New Zealand were yearly visitors. USCA Hall of Famer Archie Burchfield and his vivacious wife Betty came out for a week one year, and that's when I saw my first triple peel. The Arizona gang came over when we inaugurated the annual CalZona between the two strongest regions of the game in America at the time. They all came to visit and play croquet with CB.

Roots in Roque

CB was a great player in his own right. He came to the game already a three-time champion in the now obscure game of Roque—a variant of Croquet that was once hailed as "The Game of the Century" and played in the 1904 Olympics in St. Louis. In Roque you play on a clay or dirt court with a low wall and bank balls through arches with a short-handled, two-faced mallet, one face made of a hard surface and the other of rubber.

CB learned Roque in his hometown of Decatur, Illinois, where he raised his family and worked as a welder for 35 years in a steel mill. He quickly became a strategic master and won the National Singles Championship in 1974, 1975 and 1979. By then, CB was 56 years old and wanted to spend the rest of his days on Earth playing Roque. But where?

One Roque tournament brought him to Santa Monica, California, one of the few places in America where Roque still thrived. To CB, Santa Monica was "Heaven." To this day, he writes "Heaven" as his return address on letters. And compared to Decatur, Santa Monica is about the closest place to heaven on earth, so CB uprooted his life and moved to the salubrious seaside city, setting himself up in a modest trailer park with his trusty camper and scooter.

Discovering Croquet in Roxbury Park

But CB didn't find much Roque in Santa Monica. Instead he found Croquet. Riding his scooter down Olympic Boulevard through Beverly Hills one day, he saw the old bowling greens in Roxbury Park. The three courts were endowed by Walt Disney in the 1920s for lawn bowling but one was later converted to Croquet by an avid group of individuals led by Cesare Danova, a well-known character actor in Hollywood.

Cesare, often referred to as the Italian Charlton Heston, took a liking to CB and brought him into the game, much to the dismay of some of the other Beverly Hills Croquet Club members. In those days, croquet still had strong roots in old Hollywood, to Harpo Marx, Darryl Zanuck, Samuel Goldwyn and Louis Jourdan. Among the club's members were Philip Reed, another character actor and perhaps the best player of the golden Hollywood generation, and Maurice Marsac, the perennial French waiter in many movies, along with his wife, Melanie.

CB was anything but Hollywood. He was blue-collar stock of the first order, lacking all the refinements of the upper class, with no formal education but gifted with keen intellect, street smarts and common sense. Everything about CB was rough and unpolished, right down to his food-stained t-shirts, dirt-smudged shorts and scruffy shock of white hair. But he could play croquet. It wasn't long before CB was the best player in Beverly Hills, much to the chagrin of a few of the starched-white old school members of the club.

The best players in the club appreciated CB for exactly what he was—an unpolished diamond in the rough, a man of unscrupulous integrity and abiding honesty with a heart of solid gold. He would never cheat, saying he couldn't sleep at night if he did; and he was the first player I ever saw call a fault on himself in a big game. In Beverly Hills, he quickly became the club's self-appointed, hard-working equipment manager, setting the court to championship dimensions and devising new ways to pound the full-carrot Jaques hoops into the ancient granite-like ground—the hardest croquet ground in America.

|

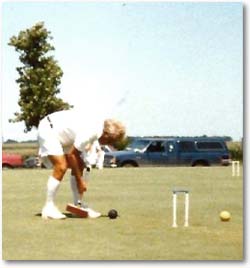

| Note CB's short-handled mallet at the 1986 USCA Mid-Western Regionals. Sheila Slimbarski photo. |

When CB first stepped onto the croquet court he brought his trusty old 24-inch Roque mallet. That didn't go over well. He was quickly informed that his mallet was "illegal." It had a rubber face on one side and a smooth wooden face on the other. This didn't faze him. Being comfortable with tools and machines, he fashioned his own mallet, keeping the short Roque handle but adapting a proper croquet head. Now he was legal and ready to play.

CB was a natural croquet player, a sure shot with crafty instincts and gifted strokes. He was so good that he never played a game in the lower flights. He started in the championship flight because he wanted to play against the best and beat them, which he did.

|

| CB outside his "hotel," parked on a side street near San Francisco's Stern Grove lawns. Sheila Slimbarski photo. |

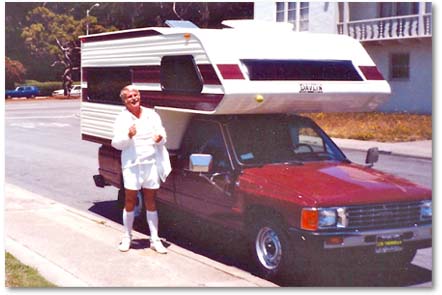

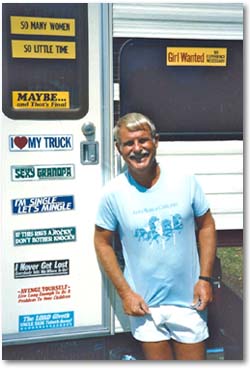

CB also became well-known for his tournament eccentricities. He'd arrive in his equally colorful camper, covered with bumper stickers ("If this rig's a-rockin', don't come a-knockin'"). That was his hotel room. He'd play croquet by day, then at night, put on his best duds and go out dancing with the ladies.

One of the great mysteries of life is how CB attracted women by the dozens. They couldn't resist him. He always said dancing was the key to his success, and he was a great dancer. He also wasn't that picky. Once, when kidded by several players about his choice of female companionship, CB cackled, "They're all the same once you get to the fast strokes." That was CB, cackling at his finest.

He was the best of teachers in one-on-one competition

|

| CB and his bumper sticker collection. Sheila Slimbarski photo. |

CB always wanted to play for something—raising the stakes to make each game count, just as in a tournament. Sometimes we played for a dollar, sometimes for a beer. During the first few months of my apprenticeship I was CB's beer supplier. He loved a good, cold beer after a good game. I don't remember exactly when it happened the first time, but I got better as we played and finally got to where I could actually give him a game and occasionally win. It's always awkward when the student surpasses the teacher, but not with CB. He couldn't have been happier for me or more supportive. I know he made me a better player and I like to think I made him better at the same time.

He had another prodigy as well: Mik Mehas. Mik went on to even greater glories on the court and much infamy off it. But everything positive Mik did in croquet he owed to CB, who taught him to play the game, much as CB taught me.

CB wasn't purely altruistic in his teachings. While he enjoyed watching his students rise to the top, he was grooming us to partner with him in doubles competitions, especially those with purses.

Playing for purses

In those days, one of the biggest tournaments in croquet was the Meadowood Classic, a doubles extravaganza at Bill Harlan's classy Wine Country resort in St. Helena, California. Club pro Damon Bidencope created an event that brought the best players in the world together for a week of great food, camaraderie, and the finest croquet on the planet. Most of all, it was a money tournament. First place paid five figures, and payouts continued down the line.

In the Spring of 1990 CB decided it was time I entered big-time croquet. I'd only played in one tournament—the Beverly Hills Club Championship—and won it. CB said I was ready. Like CB, I never played in the First Flight or the B's, so it was natural that we jumped right into the big money Meadowood event. CB and I were probably the lowest seeded team in the tournament, sitting at the bottom of our block. CB said it was the perfect spot—they'd never see us coming. We didn't win outright but we qualified for the knockout and advanced far enough to get in the money: $1000. It paid our entry fees and expenses.

Not that we had many expenses. CB's plan was to camp out the entire week at the Bothe-Napa Valley State Park for just a few dollars a night. I'd been there before with my family and figured it would be a good spot. It worked out okay the first couple nights, me in my tent, CB in his camper. Then it rained and I had to move in to the camper. CB served chili for supper that evening. That was my first and last time sleeping in the camper.

CB's camper was a well-known rolling landmark at many croquet tournaments.

And it was perfect for CB, living on a modest pension, social security and VA benefits. But it lacked one measure of comfort—a bathroom. For that, CB relied on the kindness of friends, of which he had many. He'd typically ask one of us if he could use our hotel room to take a shower or a bath. No problem except, as Doug Grimsley found out, CB would often get so comfortable that he'd fall asleep in the bathtub. Naked.

Another time, at the USCA Nationals in Palm Beach, CB had an actual place set up to sleep for the week, but he arrived a couple days early and needed somewhere to crash for a night. Rory Kelley and I had rented a small apartment on Singer Island but Rory wasn't scheduled to arrive until the next day. I told CB he could stay there. When Rory showed up the next morning, CB was sprawled on his bed, eating crackers and watching TV, naked. Rory rented another room.

Getting naked was never an issue with CB. One year he went to the now-defunct Virginia Open, hosted by Bubbie and Martha Grimsley at their Annandale, Virginia home. They put CB up in their small guest cottage. The night before the tournament began, tournament director Doug Grimsley asked CB if he would help him set hoops in the morning. CB said, sure, so long as Doug would wake him up.

The next morning, Doug went to the cottage door and knocked. No answer. He got a little worried—after all, CB was no spring chicken. He had a history of heart and lung problems, the result of his years in the steel plant. Doug walked around the corner of the house out to the big backyard and there was CB, wandering around, admiring the sunrise, arms spread wide, palms to the sky, proclaiming "What a beautiful day to be alive." Naked. Doug set the hoops himself.

Indeed, CB was happy and lucky to be alive on that beautiful Virginia morning. But his life didn't start that way.

Born to lose, but…

Cova Bert "CB" Smith was born to an un-wed mother in Kansas City, Missouri on January 24th, 1923. She gave him up for adoption to the Willows Maternity Sanitarium. His birth certificate says he was a "Dr. Stork Special," the child of an unfortunate 24-year-old woman of French-German descent. She played piano. CB never knew her. Just recently, he told me he's "looking forward to dying so he can meet his birth mother in Heaven." I hope that reunion is delayed for awhile.

|

| CB and his adoptive mother, Cova (left. CB at 18 months, June, 1924. Sheila Slimbarski photos. |

CB never talked much about his childhood. Being the nosy biographer type, I'd ask him about his upbringing. He'd shake his head and the perpetual glowing cheek-to-cheek toothy smile that characterized his love for life would turn into a painful grimace with a long sigh. While most people wish they could go back to the innocent days of their childhood, CB left his behind and threw away the rear view mirror.

Adoption wasn't kind to him. He bounced from place to place until he finally found a home, and a sweetheart, in Decatur, Illinois. Then World War Two exploded.

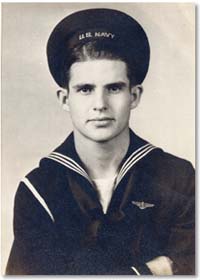

|

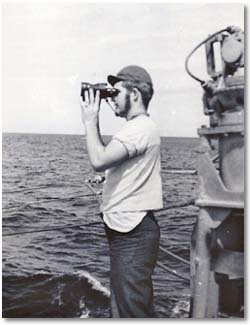

| CB Smith, USN, 1942. CB Smith photo. |

By then, CB was in sub school at Pearl Harbor, Honolulu, Hawaii. His first submarine assignment was aboard the USS Spearfish (SS-190). It was a veteran of the war by the time CB joined the crew for its 11th run. The mission took CB to the East China Sea and gave him more war than he ever bargained for. And that was just the beginning. When the Spearfish returned to Pearl it was scheduled for a major overhaul so CB transferred to another sub, the USS Seal (SS-183)

|

| USS Spearfish (SS-190). US Navy Photos. |

The Seal was a renowned hunter-killer of the sea, involved in more than its share of action, with a number of high-profile kills. CB was aboard the Salmon class diesel-electric sub for two long runs, taking him and the crew to the Sea of Okhotsk and Kuril Islands. CB described the waters between Japan and Russia as "colder that a well digger's ass in the Klondike."

|

| USS Seal (SS-183). US Navy Photos. |

Amidst Pacific War Horrors…a Honolulu Carnival

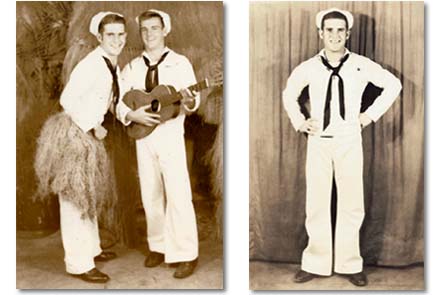

While there was great hardship and sacrifice for all the men in the Pacific submarine service, there were rewards when the boats returned to Pearl. One notable perk was that submariners were given preferential housing at the Royal Hawaiian Hotel on Waikiki Beach. They were the only enlisted men allowed to stay there. All the others were officers. CB took full advantage of the arrangement, enjoying the famous beach and the attendant vistas, especially those of the female kind.

|

| CB and a buddy on shore leave on Honolulu's Hotel Street. (left) CB Smith on Hotel Street. CB Smith photos. |

If ever a place was made for CB it was Hawaii. Suddenly freed from the bonds of a miserable childhood, he cut loose in this Paradise of the Pacific, an adult carnival that served as a real life way-station between home sweet home and the horrors of war. It didn't take CB long to find the photo booths, bars and carnal pleasures of "Hotel Street," where 200 hard working women serviced 15 million soldiers and sailors during the war years.

Like many a serviceman on shore leave in Honolulu, CB would go to one of the seedy downtown bars where he could get toasted on local beer or liquor--"Five Islands Gin" was one popular, if nasty brand. Once properly stewed, he'd wait in a long line to "climb the stairs," as the men often said. These were Army regulated "hotels" operating in broad daylight in a six block section of downtown Honolulu. On a busy day, the working women would service up to 15,000 men.

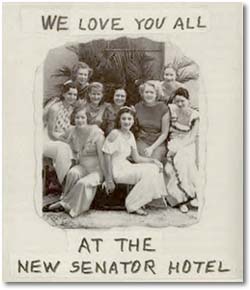

|

| The Ladies of the New Senator Hotel, Hotel Street in Honolulu. Ted Chernin photo. |

The "room" rate was three dollars for three minutes and as CB said, "When you've been out to sea for six months, it don't take you that long." Like millions of others, CB became one of the war's "Three Minute Men." Sometimes he'd even go through the line twice.

In 2001, CB was brave enough to tell his story about visiting the women of "Hotel Street." He did so for a documentary I wrote and directed on the subject for The History Channel—Sex in World War Two. By baring his story he gave light to one of the Army's best kept secrets—the operation of regulated brothels during wartime in every major theater of combat. CB wasn't proud of it, but he wasn't ashamed either. It was something he did to make the war more palatable and have a little female companionship. And he wasn't hypocritical about it. It was a time-honored part of war. And to many servicemen, especially those who survived the bombing of Pearl Harbor, the women of Hotel Street were bona-fide war heroes for their swift action tending and nursing the wounded.

CB's own lasting memory of Hotel Street is right on his arm. "I got stewed, screwed and tattooed," he cackled. And he wasn't the only one. To this day, if you meet a World War Two veteran of the Pacific with a tattoo, you can bet three dollars that they got it, and a little something else, on Hotel Street.

"Hotel Street" was a brief but welcome respite for CB and the millions of servicemen who passed through Pearl during the war. Most of his time was spent aboard cramped, stifling submarines, living for months with 58 other men, never knowing if this day would be their last. This gave everything a sense of mortal urgency.

|

| CB aboard the USS Seal. CB Smith photo. |

Sub duty was not pretty and one of the hazards was illness. That spring, CB contracted trench mouth while aboard the Seal—a severe infection of the gums. The infection grew so bad that he was hospitalized in Guam, where doctors gave him a new miracle cure: Penicillin. Unfortunately, they gave CB too much and his system reacted badly. He would remain in the hospital through August, 1945, when America dropped the atomic bombs on Hiroshima and Nagasaki. For CB, his war duty was over.

Inventing a family in Indiana

CB was honorably discharged in December, 1945, two days before his first son was born. He moved back to Decatur and set up housekeeping with his new bride and mother of his child. For the next 38 years, CB worked at Mississippi Valley Structural Steel and raised his family with all the love and affection he'd been denied as a child.

His daughter, Sheila, born in 1947, said she and her four brothers had an idyllic childhood. In many ways, she felt CB retrieved his own childhood living vicariously through them.

CB had many hidden talents. Among them, he was a master kite builder. But not just any kites. Along with the normal kites that kids fly, CB built miniature, postage-stamp sized kites that he flew with a fishing pole. He and his boys entered their kites in the annual Decatur Kite Festival and won first prize. It was the first of many competitions for CB.

Somewhere along the way he picked up Roque. With his superb hand-eye coordination, his innate intellect, never cultivated but always present, and his fiery competitive spirit, CB became a champion Roque player.

By the time his kids were all through college—every one of them—CB decided it was time to pursue his own dreams. In the early 1980s he and his wife split up and CB left Decatur behind to head west and live the life of a Roque-playing bachelor. It was a bold move for a retiree, completely uprooting his life. But that just epitomizes CB's free spirit.

He bought the camper and was on his way to Heaven to enjoy his own second childhood.

CB doesn't remember exactly when and where he got started in Croquet, but the lawns of Beverly Hills became his daily haunt. Roxbury Park had a Senior Citizens Center where he could get a hot lunch for less than a dollar. Then he'd play a game or two or three—as many as he could get.

In 1986, the USCA held the Mid-Western Regionals in Bourbonnais, Illinois, just a couple hours south of Decatur. It gave CB the perfect opportunity to visit his hometown and play in a big tournament. It was held at the Bon Vivant Country Club and hosted by Merlin Karlock, one of the great gentlemen of the era Playing with his short-handled mallet, CB employed the "out-game" to great success and won the Championship Singles.

Two years later he participated in the inaugural California Challenge Cup and won that, beating many of the early California croquet greats, including Frank Estrada, Hans Peterson and Sal Esquivel. Now CB was on his way to being one of the top players in America.

As a teacher, CB insisted his students learn the "Arizona" way—play Association Laws for the first three months and learn croquet shots without worrying about deadness. Then he switched us to American Rules. It was confusing at first but once the strokes were in place we all became better players.

In 1992, CB and I went to the USCA Nationals in Southhampton, New York. It was one of the strongest fields ever up to that time. Reid Fleming won his 3rd National Singles title. Harold Brown, teaming with Bob Yount, won the doubles—an exciting moment for Harold and everyone who knew him. Like CB and Archie Burchfield, Harold was a colorful character who enjoyed bucking the aristocratic reputation of croquet.

The sweetness of remembered victories

But the biggest bucking of all came in the Seniors National Championship. USCA founder Jack Osborn was the odds-on favorite to win, but he had to go through a field of tough competitors, including CB. They met in the semi-finals. Before their game, Jack told CB if he played the "out game" he was going to get a croquet lesson. CB just cackled at that, kept yellow out, and by the end of the game the lesson was Jack''s. CB went on to defeat Chuck Reif in the final, claiming a national singles title.

The following year, CB won the Southwest Regional Senior Championship at Sherwood Country Club in Thousand Oaks, California. Club owner David Murdock—the Dole Pineapple king—was on hand to watch the finals. His beautiful young wife, Maria, daughter of Rosemary Clooney, gave out the trophies. When she handed CB his sterling cup, he gave a wide grin, embraced her and kissed her flush on the lips. Then he poured beer into his trophy and toasted his victory with a big swig. It was a moment to savor, even for Maria.

CB loved playing croquet tournaments and competing at the top level of the sport. He liked nothing better than to match wits and skills with the best players. Win or lose, he just loved the game. But by the end of the 1990s his physical stamina began to wane. It became harder for him to play a typical grueling croquet schedule of four or more games a day. He got to where three games were the best he could do before running out of gas. And so that was that. He wasn''t about to step down to the B flight. If he couldn't compete with the best, he had no interest in continuing.

Life after croquet includes poker

|

| In the late 1990's, CB decided it was time to retire from competition, and that meant retiring from croquet. If he couldn't compete with the best of them, he would switch to another game. Erv Peterson took this photo at California's Indian Ridge at just about this time. |

In his retirement from croquet, CB turned to another competitive game—poker. To this day, CB goes to the card clubs in Los Angeles and plays in small, no-limit Texas Hold-‘em games. I can just imagine him bringing up the old periscope when he gets a good hand, ready to fire one into the pot, announcing a raise with that trademark cackle.

Croquet has known many wonderful, colorful players over the years. But there's only one CB Smith. I don't know if he'll ever make it into the Croquet Foundation of America's Hall of Fame, but he's in mine.

Rhys Thomas, 55, is a writer by profession who lives in Los Angeles with his wife Michelle. It's a handy base for the hundreds of hours of documentary television he has written, directed, and produced for The History Channel, National Geographic, Discovery, ABC, NBC, Fox, Military and Travel Channels, earning him an Emmy nomination. Thomas has held many management posts for the USCA, and recently retired following two elected terms as Management Committee Member of the World Croquet Federation, and USA Representative to the WCF for 16 years. As a championship croquet player since 1988, he has represented the USA on three Solomon Trophy teams and in three WCF World Championships, and was the 1996 US MacRobertson Shield team coach and manager. He has also managed many prestigious croquet events at Sherwood Country Club. In 2003 He served as Tournament Referee for the Mac. He hopes his retirement from management in 2012 will enable him to play more competitive croquet and perhaps even regain championship form.