|

Back to |

| The Front Page |

| People |

|

My life in croquet: Part Two |

|||||||

|

by John Prince Posted September 22, 2006

|

|

||||||

In the decade following John Prince's sudden emergence as the brightest rising star of croquet in the Southern Hemisphere, his eminence on the court assumed the brightness of a sun. More than anything else, he wanted to compete against the best players in the world, and much more often than not, he prevailed in those contests. People began to speak of him as "the best croquet player in the world," and his playing record against Solomon and Aspinall of England in this period confirmed that assessment. Here's Part Two of the three-part memoir.

|

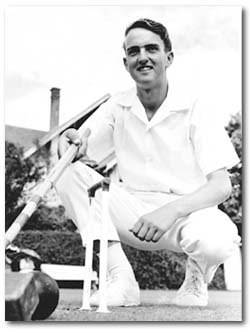

| The 17-year-old John Prince, having scored impressive victories in the 1963 MacRob series, created a sensation a week later in his first appearance in the New Zealand Championships, winning the Mens Singles title. |

Of the play I don't remember a lot apart from Ashley's intentionally running rover from behind hoop 3 to snatch victory from the jaws of defeat against Jean Jarden. It was obvious that Ashley's absence from the Mac the previous year had adversely affected the outcome from New Zealand's perspective. During the tournament Jean's No.1 fan - her husband Ben - was convinced that Albert Saalfield, a visitor from Australia, was gaining some advantage from the unusual glasses he was wearing. Though not a player, Ben was nevertheless an astute observer of the game. His suspicions were further aroused when Albert refused his request to look through them, but he was never able to determine the facts of the matter.

Albert - obviously somewhat eccentric - became the victim of his own invention in a mildly humiliating public display. He was convinced that as the law stated literally, after your opponent ran one-back you were entitled to a lift. You therefore must lift the ball, Albert insisted, not trundle or hit it with the mallet. No one took him seriously. But when entitled to a lift himself, on this occasion he forgot his own interpretation and trundled the ball off to baulk, whereupon his opponent - the also somewhat eccentric but delightful Cam Paynter - shouted out with glee, "You didn't 'lift' the ball, so you must put it back, you've had your turn!"

A near unbroken string of triumphs

|

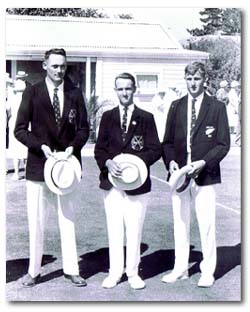

| Three young members of the 1963 NZ MacRob Team at Napier, New Zealand on the first morning of the Test Match with England. (Left to right) Ralph Browne, John Prince and Tony Stephens. |

In 1967 I won the NZ Open Singles for the first time and continued for the fifth year my record of remaining unbeaten in the Men's Championship. I notched up a consecutive run of nine men's titles from 1963-1972. (I didn't play in 1965).

In 1968, playing in Christchurch and for the first time in the South Island, I won both the Open and Men's Singles and the Doubles with Jean Jarden. I recall the Men's final against A.D.M. Ross, a promising player a couple of years my senior, where I completed two triple peels and he didn't take croquet.

The scene during the fortnight at United (Headquarters) was impressive, with up to 200 spectators most days. Because I was a youngster and played adventuresome croquet, I had quite a following. I recall towards the end of the fortnight beginning to find the adulation from some a little tiresome, but then was reminded by Keith Woollett to accept it graciously.

I'd become close friends with Keith and his wife Hazel, and over the years to come we were to have lots of fun together. They lived in the small town of Ohakune on the slopes of Mount Ruapheu and were pretty much the only members of the local croquet club. Once when we played there in the days before Keith built a lawn on their own property, Hazel found a child's pram in the corner of the clubhouse and turned it into an admirable drinks trolley. Whatever we did together, we did with a sense of style that was just enough off-centre to be memorable

My first competition overseas: the Australian MacRob

In 1969 I again won the Open and Men's titles and was appointed Captain of the New Zealand MacRobertson team. I got to visit Australia for the first time, but it was not a very enjoyable tour. We traveled with a "team" of eight to pick from, so there was much added tension off the court over which six would compete. The Manager Herbert Ford and I were rarely in agreement. In hindsight, I can acknowledge that at the age of twenty-two I was probably too young for the role.

The poor old Aussies were not in much better shape with their squad of twelve, and they added unnecessary strife by having an amazingly strict dress code! One player absolutely refused to wear the official Australian "team" hat, preferring a comfortable old favourite of his own - so he never got to play! After the series Bruce Buchanan wrote a delightful piece for "Croquet" (the English croquet gazette) in which he commented with sardonic humor that it wasn't fair that the Australians, who looked so nice in their uniforms, were not protected by their officials from the unsporting attitudes of the visitors. He noted that some of the Englishmen never wore hats of any kind and - horror of horrors! - two New Zealand men wore shorts.

There was an amusing moment during the third game of a doubles match held over and played after the other matches were finished. William Ormerod, playing for England, made an early break to 4-back and later went to rover. His partner Douglas Strachan was enjoying the relaxed atmosphere and chatting away to his opponents, the Woolletts, and when it came to his turn he started a triple peel on his partner, much to William's amusement. We all waited, suppressing giggles, until he came to rover to see William's clip on the hoop. This display became known for the rest of the tour as "Strachan's phantom triple".

Early in the MacRob series, the games were shown "live" from Adelaide on Australian TV's Saturday afternoon sports slot. John Magor and I played an exhibition singles game, with Bernard Neal and John Solomon providing the commentary. It ran for about 90 minutes and happily went without a hitch, including a contact leave and a triple peel - so we didn't have to worry about confusing the TV watchers with a more complex game than was necessary.

These matches were played before large crowds, especially at Adelaide, where many players had stayed on to watch following a big Association tournament there. The brightest star of the series was Nigel Aspinall, whose very aggressive style worked for him because of his superb shooting. Playing in the No. 1 position for my team, I twice scored wins against both John Solomon (England) and Tom Howat (Australia).

|

| Competition portraits of some of the star players in the 1969 MacRobertson Series in Melbourne. (left to right) Tom Howat (Australia), Nigel Aspinall (Great Britain), John Solomon (Great Britain). |

In my first match against Howat he gave contact in the first game but I was able to go round off the leave to 4 back. Although I made a leave suggesting he should play with his forward ball, Tom without hesitation lifted his ball for hoop one, hit and finished the game. While his tactic of giving contact was not unknown to me, when combined with his outstanding shooting, it made me a little anxious should he gain the iniative in the second game. However, strangely enough, the next two games were identical and winning them gave me the match. In each game, I made the first break, he hit the lift but became hoop bound after running hoop one, and I finished with a triple peel.

My two matches against John Solomon were won comfortably in straight games, but it was clear that John was far from well during our first encounter. No one had advised him not to drink the water unless it had been boiled first!

The second test match - NZ vs Australia - was played in Melbourne, and I again played against Tom Howat. I was underway with a break having just made hoop two when Tom stopped me to explain that he thought the court was not the full length. The Referee produced a tape and, sure enough, it was one yard short. As the error was confined to the distance between hoops 2 and 3 to the north boundary, a correction wasn't difficult, with a string being used to define the correct line - but I firmly refused Tom's suggestion that we start again! The match continued and I won a close first game but ran away with the second. Nigel Aspinall ended my unbeaten singles run in the Mac with a comprehensive victory in the third test (England vs NZ) which included a 5th turn triple. Such a hammering, coming as it did at the end of a tense time, wasn't helped when Herbert Ford, our Team Manager, noted in passing what a humbling game croquet could be.

The First Sextuple in Competition

During the mid sixties I had become aware that John Solomon was attempting sextuple peels in some of his matches and as I already had a description of how to go about it from Pat Cotter's book TACKLE CROQUET THIS WAY, I included it in my practice routines.

The set-up after the first break to one-back was opponents cross-wired at hoop one, partner (for hoop 1) midway between one-back and the north boundary open to both opponent balls and the striker's ball in the jaws of one-back.

The latter is not always that easy to achieve; several times in trying to stop the ball in the jaws I sent it through, instead. This leave was known as the “Standard Sextuple Leave” although later, it became known as the “Ladies Sextuple Leave”--possibly the invention of someone who had never completed one in a match!

I saw John Solomon attempt a sextuple during the 1969 MacRobertson Shield Series in Australia, but he was never to actually complete one in a match. However, following that series Solomon visited New Zealand and in a friendly doubles partnering Arthur Ross at the Hastings Croquet club he succeeded. I recall nearly finishing one myself during the NZCC Best Eight at Timaru early in March 1970 against Keith Woollett on a very uneven court at West End Club; but all the peels completed I missed the peg-out from about four yards! But, having got so close, I now knew it could be done.

A few weeks later I succeeded in the final of the Hawkes Bay Croquet Association's Easter Invitation event at Hastings against Frank Bennett, a local player who played off a minus handicap. Arthur Ross was watching and was one of the first to congratulate me, saying it was the first he'd seen completed in a match. He recalled doing one himself but said it was either in practice or during a friendly. It wouldn't have surprised me if he had done them in match play. I was aware that Sir Francis Colchester-Wemyss, a member of the 1935 England MacRobertson Shield team had written in Ross's book CROQUET AND HOW TO PLAY IT (1933 second edition) the following, “In a recent Dominion Champion Cup, Mr. Ross won all his 18 games; in 11 of them he bought of a triple, in one a quadruple, and in one a quintuple peel”.

News arrived from England in July of 1971 that Keith Wylie had completed a delayed sextuple against Nigel Aspinal in the final of the British Open, a magnificent feat, and against such a formidable opponent but as that was in June or July 1971 I had got there about 15 months before Keith. It's a little like being the first on top of Mt. Everest, and that was a Kiwi too!

The delayed sextuple has a different leave to the standard. The opponents are again cross-wired at hoop one but you leave yourself a rush towards one-back from corner three. It's an identical position to an earlier four-back leave, which was the standard leave prior to the laws allowing a lift at one-back.

Keith said, and may have written, that his intention using the corner three leave was to lengthen the opponent's shot and that he thought of it as “one back” tactics rather than a sextuple leave in itself. He liked his chances of winning a game if he got four peels done and a good contact leave, finishing up on peg and penult before his opponent scored rather than going all out for the six peels and breaking down. I'm not sure now if he advocated pegging out his forward ball or not. But obviously the peeling all went very well that day against Aspinal at Hurlingham. Keith, John Solomon and others experimented with other leaves, but the corner three leave has become the standard these days.

The ultimate experience: croquet in England

I only just made the 1974 MacRobertson test team, having been somewhat critical of the New Zealand administration from time to time. I nearly paid a high price for not agreeing with the people in charge of the sport nationally. To their credit, they got over it sufficiently to award me a place on the team, and it was a wonderful tour, made all the more special because my wife could enjoy it with me.

We met many interesting people - including Croquet players, stars from the past like Freddie Stone, Maurice Reckitt, Daisy Lintern and Hope Rotherham, plus old friends from the 1963 and 1969 series and a whole lot of new ones, including a fellow rugby follower and great social companion: William Prichard, a member of the Great Britain team and a fiercely patriotic Welshman. The NZ team played in Scotland against the Scots at Gleneagles Hotel - a wonderful experience - and then at Colchester, Budleigh, Nottingham, Cheltenham, and Compton, all the famous venues I had read so much about.

|

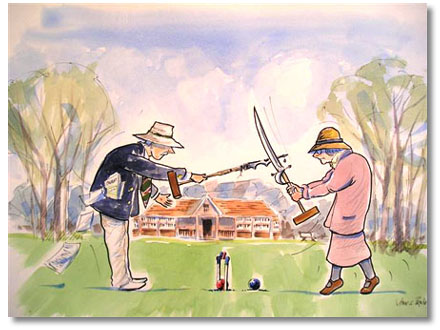

| Among the notables Prince met on his trip to England with the MacRob team in 1974 were Maurice Reckitt and the great female champion D.D. Steel. Though well past their playing prime, their competitive spirit at Roehampton is celebrated in the cartoon Prince titles "Reckitt draws Steel." |

Playing at Hurlingham for the first time was fantastic, despite a little subtle gamesmanship from Maurice Reckitt. While Aspinall was making the first break against me, Maurice asked if I remembered our previous encounter in 1969! I remembered it well, but this time I got my revenge. Such was Nigel's status that Australian supporter Biddy Dodd said to me at a social event, "I hear you beat Nigel, that was a surprise!" To which I bravely replied "Oh, I don't think so."

I took great pride in finishing the series with a 3-0 record against Aspinall, together with a five-out-of-six result playing at No. 1 in the doubles with Alan Anderson. Along with John Solomon, Nigel was one of the best players I've ever played against, and the challenge they presented was one I was always keen to rise to. I always wanted, more than anything, to play against the very best. We had finished that series in second place, defeating Australia 2-1, but clearly we'd laid down a challenge. The British holders had won well enough, but they had not dominated at the top of the order as they had so often in the past.

My partner Alan Anderson beat me in the British Open semi-finals that followed soon after the MacRob, and he then faced Aspinall in the final but lost. I was, however, very pleased to win the British Doubles title with Gordon Rowling and still remember an excellent final against Martin Murray and Andrew Hope.

At the conclusion of the tour, Maurice Reckitt expressed the opinion, relayed to me by Lil Rawlinson, the NZ Team Manager, that "John Prince is the best player in the World." It was little consolation, for I'd desperately wanted to win the British Open title. Perhaps then I'd have felt I deserved such an honour. But it was kind of him to make the remark.