|

Back to |

| The Front Page |

| The Game |

|

The origins of carry-over deadness in American Rules by David Drazin Layout by Reuben Edwards Posted December 28, 2005 |

This article, the product of ground-breaking research published here for the first time, provides the scholarly underpinning for another recent article in Croquet World about the fabled writers, artists and actors who, in all probability, popularized carry-over deadness in the 20s and 30s and made it a permanent part of the American game, eventually codified with the formation of the USCA in the 1970s. For more on Herbert Bayard Swope and the influence of the Algonquin Round Table on croquet's development, see Bob Alman's interview with Herb Swope Jr, entitled "Inventing the American Game."

When the history of croquet in the US is retold in years to come, the origins of carry-over deadness - the requirement that a ball, having roqueted another, should run its next wicket in order before roqueting that other ball again, in whatever turn - will doubtless figure prominently. Players familiar with both American Rules and the international game are generally agreed that carry-over deadness is by far the most distinctive characteristic of the domestic American game.

|

| The author examining the Rendell Rhoades Croquet Collection at the Rutherford B Hayes Presidential Center in Fremont, Ohio. |

Beginning as one, the games evolved on separate continents

When croquet burst upon the scene, chiefly in the English-speaking world, in the early 1860s, the game was played in much the same way the world over. Certainly there were variations between the rules of the game as played in different countries, but such variations were probably far less marked than variations between the rules recognised at different venues within countries. And, importantly, wherever croquet was played, there was no carry-over deadness. Or, more strictly, there was no carry-over deadness in the rule books of the time. Though there is no knowing how the rules in those books were interpreted by particular groups of players - and no doubt they were construed very differently in some places - the rule books were generally in agreement on this specific issue. So, for example, the best-selling handbooks in the UK and US ruled as follows:

'A player may croquet any number of balls consecutively; but he cannot croquet the same ball twice during the same turn, without first sending his own ball through the next hoop in order.'

(John Jaques, Croquet: The Laws and Regulations of the Game, London: Jaques and Son, 1864, my italics)'A ball having roqueted another ball, is at liberty to croquet or roquet-croquet it or proceed on its round; providing that the playing ball has not already in that tour roqueted that same ball since making a step on the round.'

(Prof A Rover, Croquet: Its Principles and Rules, Springfield, MA: Milton Bradley & Co, 1866, my italics)

American croquet in a time warp

|

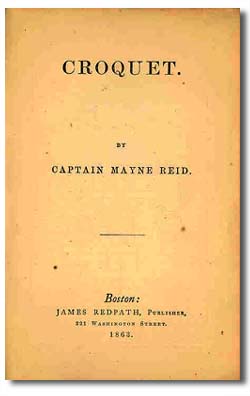

| Croquet (1863), by Capt Mayne Reid, the first rule book known to have been published in the US. Rule 90 is wonderfully clear: 'The commencement of each new tour of play restores a ball to all the privileges of the game.' |

Fast forward to 1977. How come then that carry-over deadness was adopted by the USCA on its foundation for the American Six-Wicket and Nine-Wicket games? In a word, the evidence, such as it is, points to a horrible mistake a long time before, probably around 1900. Tracking back from the first publication of the USCA's American Rules as a supplement to Charlton and Thompson's Croquet: The Complete Guide to History, Strategy, Rules and Records (1977), we can see a clear enough trail all the way back to a big bang at the turn of the century. The trail is defined by inference and circumstance but, with luck, the recollections of living witnesses and the discovery of documentary sources will either furnish future historians with more solid support for my present hypothesis or lead them in an entirely different direction. So, working backwards, let us pick out the hypothetical trail.

Influence of the Algonquin Round Table players

Three giants mark our backward path: Jack Osborn (1929–1996), founder of the USCA, Henry Bayard Swope Sr (1882–1958), leading newsman of his day and croquet host extraordinary of the Algonquin Round Table, and Herbert Bayard Swope Jr (born circa 1914), contemporary media mogul, latter-day croquet supremo, and contributor of a recent memoir to Croquet World Online Magazine. Writing in his book Croquet: The Sport, Osborn tells us that the code of American Rules was compiled in conclave by the five charter clubs of the USCA - the Westhampton Mallet Club of Long Island, New York Croquet Club, Palm Beach Croquet Club, Green Gables Croquet Club of Spring Lake, NJ, and Croquet Club of Bermuda - with the help of John Solomon and Nigel Aspinall, leading British players. It is not generally known who said what and to whom, and we have it on good authority that the debate was fairly fraught, but this much is certain. Carry-over deadness, observed by most if not all of the charter clubs, was adopted despite misgivings felt by many seasoned players on the West Coast and elsewhere.

Osborn himself seems to have been very strongly committed to carry-over deadness and his views must have carried considerable weight among his fellow rule makers. In 1974, three years before the formation of the USCA, he had written this rule into a croquet manufacturer's rule book:

'When a player's ball hits another ball it is considered DEAD on that ball until the player has made his next wicket shot, but the player may play off it.' (Rule Book: Tournament Croquet, Skowhegan, ME: Forster Manufacturing Co)

This closely foreshadows the first official edition of American Rules:

'When a striker's ball hits another upon which it is alive, it is immediately dead on that ball until the player has made his next wicket, but he may play off it as in Part 4, Rule 26.' (Rule 33) (Charlton and Thompson, Croquet: The Complete Guide to History, Strategy, Rules and Records, New York: Turtle Press, 1977)

So we get the idea that Osborn didn't want to be confused by facts: his mind was already made up!

How then did carry-over deadness come to the five charter clubs in the first place? We very much hope that old members past or present, even the original rule makers themselves, will come forward with their recollections, for here we have no specific dated documentary evidence whatever. And yet the facts are well documented. In the recent feature in this magazine, Swope Jr speaks categorically of the key events. His father, Herbert Bayard Swope Sr, hosted the legendary croquet meets of the Algonquin Round Table at his homes in Great Neck and Sands Point in the 1920s; father, son, and their associates played much the same game with carry-over deadness right through to the 1960s, after the foundation of the charter clubs; Swope Jr and Osborn collaborated closely in the promotion of croquet; and, between them, they played major roles in the formation and management of the Westhampton Mallet and New York Croquet Clubs, which were later to seed the USCA. How the other charter clubs came by their rules remains to be told, but we gather they were cloned with Westhampton and New York by common parentage.

Let us just remind ourselves that Herbert Bayard Swope Sr, winner of the first Pulitzer Prize for Reporting in 1917, was a very big man indeed. Writing in 1931, Ralph Pulitzer, son of founder Joseph Pulitzer, raised a toast to him:

'Now here's to Herbert Bayard Swope.

God save the King. God help the Pope.

And God protect the President

From this demure, retiring gent.

He taught George Rex to put his crown on,

Queen Mary how to put her gown on,

And David Windsor, Prince of Wales,

To fall from horses and for frails.

Explained just how to outmaneuver

Depressions to our Mr Hoover;

And for the Pontiff, as a pal,

He's written his encyclical ...'

In his recent conversations with Bob Alman, editor of this website, Swope Jr asserts that his father, the Algonquin set, and their croquet friends played carry-over deadness from the time his father opened his lawn at Great Neck, Long Island, in 1922. And we have independent confirmation of this fact from no less a figure than Harpo Marx:

'The crucial game got under way in deathly silence. Then, halfway along, when it was his turn to shoot, Swope asked Woollcott to refresh his memory on who was dead on who. He'd forgotten. (Once you've hit, say, the yellow ball, you're dead on yellow and can't hit him again until you've gone through a wicket.' Harpo Marx with Rowland Barber, Harpo Speaks (Bernard Geis Associates, 1961)

Note in passing that the glitterati of the day played without a deadness board. Today we would say that was crazy, but we might thereby misunderstand the ethos of their game, in which memory and forcefulness of character in resolving differences were as highly prized as ball skills.

So where did Swope Sr get carry-over deadness? Certainly not from the contemporary mainstream croquet literature. The biggest US sports publisher of the time was the American Sports Publishing Company of New York, a wholly owned subsidiary of AG Spalding & Bros, leading manufacturer of sports equipment. And, in their popular contemporary handbook, they held to the orthodox deadness line:

'A player, in each turn of play, is at liberty to roquet any ball on the ground once only before making a point.' (Rule 19, my italics) (Croquet: Rules of the Game (New York: American Sports Publishing Co, 1916)

Swope Jr tells us that his father picked up croquet in England during the First World War when working in Europe as a newspaper reporter. Carry-over deadness was unknown in UK Croquet Association circles; but tournament play was frowned on by the British croquet establishment while the world was at war, and we know that Swope Sr was never a paid up member of the Croquet Association.. So it is possible that he picked up carry-over deadness, along perhaps with other aberrant rules, from British hosts who were unfamiliar with the 'Association' game. Or, having been steeped in the official Croquet Association game, seeing on his return home that that game would never wash among his new-found croquet friends in Long Island, he may have taken up carry-over deadness along with their mode of play.

Another fascinating possibility is suggested by Ely Jacques Kahn Jr in his life of Swope:

'Woollcott maintained that the breakthrough in American croquet occurred in Englewood, New Jersey, one day in the spring of 1920. A group including Neysa McMein were playing the childish version there, on a smoothly groomed and narrowly constricted lawn. "Let's play without any bounds at all," Miss McMein suggested, and a revolution was under way. The word quickly reached Great Neck and touched responsive ears.'

But here the evidential trail peters out, and we are left to conjecture.

And here it is important to distinguish two separate questions: who was the player from whom Swope Sr acquired carry-over deadness, either at first hand or indirectly - that is, who invented or discovered it - and what was the source from which that player invented or discovered it. We shall probably never know the answer to the former question. Swope Sr is long gone and we may presume that, if he knew this secret, he took it with him to his grave. And, anyway, who was the first perpetrator of carry-over deadness is perhaps hardly that interesting. More intriguing is the question where it came from.

Of course, it could easily have arisen as an innocent misconstruction of the rules of the game as recorded in a respected handbook. Most of the handbooks that appeared in the nineteenth century were poorly put together, many were apparently written by professional sportswriters who had little understanding of the game, and some were frankly impenetrable. So any new owner of a croquet set who relied on the printed word to make a game of it would probably have to improvise, and in so doing very possibly invent carry-over deadness for himself.

A pivotal mistake perpetuated in print?

But another intriguing possibility presents itself. Looking through my pre-1922 American rule books, I found just one which prescribed carry-over deadness, and this is what it says:

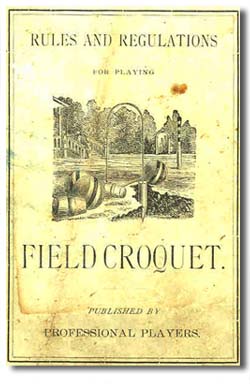

'No ball except a rover can croquet the same ball twice, until the croquet has passed through an arch or hits a stake.' (Rules and Regulations for Playing Field Croquet, by 'Professional Players')

|

| Possibly the original source of carry-over deadness: Rules and Regulations for Playing Field Croquet, published by 'Professional Players', circa 1900. |

Just one more query to tease present and future historians: If this lightweight eight-page rule book set carry-over deadness cascading down the generations, how did the carry-over deadness rule it begot come to be written? My guess, for what it is worth - and I must emphasise it is only a guess - is that it is just a horrible mistake, an error or oversight. Plagiarism was rife in sports publishing at the time, so most croquet publishers would have seen no point in hiring a writer who really knew the game to produce a rule book. There were plenty of existing rule books out there to copy from. And, if the compositor happened to miss out a few crucial words like 'in the same turn', no one might have noticed!

History is a funny thing. As we have learnt from chaos theory, an insignificant event can have cosmic consequences. If carry-over deadness was misbegotten by a compositor's error more than a century ago, it is still the most distinctive element of the variety of croquet favored by the majority of American players at the dawn of the 21st Century.