|

Back to |

| The Front Page |

| People |

|

Working and playing in San Francisco: Bob Alman Memoir, Part Two |

|

by Bob Alman photos by Carl Hanson, Mike Orgill, Bob Alman, and others as credited posted on April 18, 2019

|

The narrative continues in the third-person voice of Part One, as Bob Alman declares himself a mature adult in his thirties, but realizes he is totally unfit for the corporate world. After the book project at Werner Erhard and Associates ended, he found distasteful several freelancing jobs in downtown San Francisco. Their corporate atmosphere seemed to him chilling and the executives related to Bob himself as alien. He had learned how to do real work, but none of the jobs he found seemed to him worth doing. Casual croquet helped; he had not yet discovered the sport, but played 9-wicket regularly. He had no idea, at the time, that he would have a major role in creating the first two-court croquet club on public turf in America, and preside over what became the strongest players' club on the continent, and then....

After the book project at Werner Erhard & Associates ended, the San Francisco Chamber of Commerce commissioned Bob Alman to write their semi-annually revised, updated, and copiously illustrated booklet called SAN FRANCISCO, HEADQUARTERS CITY as a relocation pitch to corporations. In doing basic research, Bob noticed that previous issues had emphasized--falsely and misleadingly, he thought--the centrality of the Bay Area as a transportation hub and the advantages of the area's labor market.

Nobody would believe a corporation could find cheap labor in San Francisco, so why should they imply that? Corporations moved to San Francisco because the CEO and top officers and their wives preferred to live in the City. But the Chamber didn't want their booklet focused on the most relevant attractions of the City for affluent people, so they paid him and sent him on his way. Later he saw that they had actually used most of the "lifestyle" features he had put together, but they hired someone else to give their pitch the spin they had always used before--with transparently misleading statistics about labor and transport.

Then he was invited by an acquaintance he had met at the Chamber to fill in as editor of the monthly magazine of Bechtel Corporation at their downtown headquarters when their regular editor went on extended sick leave. It was the world's biggest privately-owned engineering firm, and the monthly magazine needed to be edited to look respectable. Bob routinely asked Bechtel corporate to approve all the original copy before publication, no problem. But he didn't ask them to approve the cover presentation. (He had always enjoyed choosing the cover art.)

Dislocated again--by a camel

So for his third issue of the Bechtel monthly, he found a gorgeous picture for the cover, well-composed, eye-catching as well as thought-provoking: a camel standing in front of an elevated Bechtel pipeline receding far into the desert, looking at the camera with a kind of screwy "what's this?" expression on his face. The Bechtel brothers hated that cover. They thought it suggested the camel was confused and annoyed (although clearly the camel could walk under the pipeline) and critics could use it as evidence of bad things the Bechtels were doing to the Middle East. So they hired another fill-in editor.

After those experiences--doing a good job that wasn't wanted--Bob felt he would never fit into the real world and realized he had confronted those experiences throughout his life. At college, in journalism, he had created a huge and consequential stink by writing a satirical editorial criticizing Governor Jimmy Davis and the Louisiana State Legislature for cynically passing laws blocking New Orleans school integration when the politicians knew very well those laws would eventually be knocked down in the courts. The article was picked up by the AP and published nationally.

It was only the truth, but the Louisiana politicians would not tolerate it. Bob had not been expelled (perhaps because the two journalism students expelled in the Huey Long era had been offered scholarships all over the world, prolonging the bad publicity) but the legislature informed the journalism school that if Bob Alman wrote one single by-lined word in the daily newspaper for his entire last year, they would deny the school 22 million dollars.

Bob didn't take the death threats seriously, He much enjoyed the underground celebrity in his final year. And he had a perfect excuse to give his parents for moving to California after graduation--because it was much too early, in 1961 in the South, for any newspaper to hire a white integrationist.

Finding a job worth doing wasn't that easy, so...

Jobless in the fall of 1975, he couldn't help recalling his idyllic time on the book project at Werner Erhard & Associates: the intimate environment, the camaraderie of the staff, the genuine sense of purpose, the sheer enjoyment of expressing who he really was, and sharing everything with everyone, all the time. At WE&A he had been trained to seek out and honor the truth--a commodity, it seemed to him at the time, that was appreciated nowhere else.

|

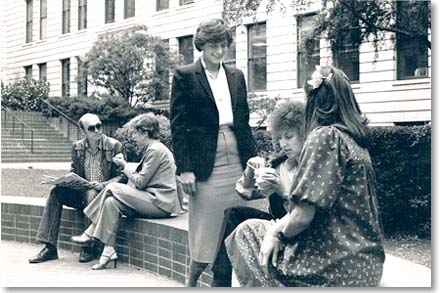

| This publicity photo art directed by Bob (far left) was shot in the courtyard of the downtown San Francisco building where Werner Erhard & Associates was headquartered; concerts were sometimes give here for the staff and key assistants. |

So in the fall, he visited the Human Resources department of WE&A to say what many others had earnestly said before him: "I'll do anything. I just want to work here again." The "again" was useful. He was already known there. Werner Erhard himself would give him a pass. He was soon Features Editor of their new monthly magazine, The Graduate Review.

It occurred to him later that this was the only time in his life he would ever go to any organization and say those words. Later, in the croquet world, it would the goal that attracted him, getting something or other done, the partnership with other players in pursuit of common goals and the cameraderie--and not the corporation or the job titles.

|

| The business card Bob designed in 1985 put himSelf first, then listed various activities in his life, with an extra box at the end to allow for new possibilities. The first two he was already doing for "freelance" money; the last two were done only for pleasure, at the time. |

Whether it was The est Training itself, or those five years of working at the world headquarters in the late 70's, he left staff thinking he could do anything, but without any sense of what that would turn out to be. The card he devised at the time survives as proof that croquet was nowhere near the top of the list of possibles, but next to last; he and his buddy Mike Orgill were not to discover USCA croquet for at least a year after he left the est staff in 1980.

Discovering the sport of croquet

It happened when Mike noticed an item in the San Francisco Chronicle about a demonstration by the United States Croquet Association on a former bowling green (and now a putting green) on Sloat Boulevard. There Mike and Bob witnessed for the first time croquet played with heavy equipment on short grass by people who looked very skilled. They already had a little club there, formed by Steve Swig, Tom McDonnell, Jack Brown III, and other socially prominent people, and permission from park authorities to play on the entire lawn every Sunday.

Mike wanted to join the club. Bob said it looked much too serious, and he didn't want to pay a $300 initiation fee plus annual dues of $200. But Mike persuaded him to join, and soon they were learning the rules of the USCA's brand of croquet and meeting other miscreants who came to play--including John Taylor, Ed Breuer, Margaret and Hood Chatham, Hans Peterson and the Berkeley gang.

That one decidedly unlevel lawn--for which the socialites had procured permission for Sunday play on a green used the rest of the time for golf putting practice--was the infamous "San Francisco Hill Course." By the time Mike insisted they produce a tournament, the two of them were among the best players in the club.

|

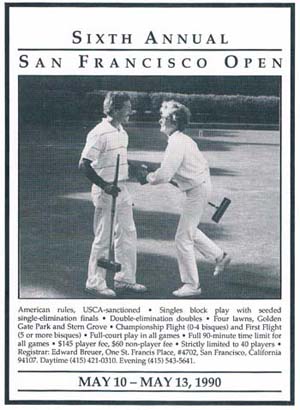

| Bob is among about 30 players in the first SF Open in 1985, turning here in the checkered hat to cue the brass quartet in probably the most over-produced croquet tournament in the West, up to then. |

Their first SF Open, in 1985, was much over-produced, including a brass quartet and formal ceremonies, and attended by thirty-something players from around the West. It was played much like the tournaments in the East at that time, as a double-elimination event, in singles only, on two adjacent half-courts on that bumpy lawn. The producers had decided early on that their annual Open would never exceed four days of play. Somewhere around this time, in the mid-80's, the "new members" of the club (the non-socialites, basically) had asked the five-member board---including Swig, McDonnell, and Brown, etc.--what they could do about getting more and better courts. Nothing, the founders said, because they had already used their influence to get part-time playing privileges on the Sloat Boulevard "hill course."

The hugely consequential Radical Caucus

Realizing that the "new members" far outnumbered the old ones, Alman decided to call a meeting at his apartment of a "Radical Caucus" aimed at discussing the issue of bigger and better courts and other improvements, Thinking, perhaps of the "nothing and nobody left out" ethos of the est organization, he invited by postal mail everyone in the club, including the founders. Only the "new players" came. (Soon after that, word spread that the founding members had called a meeting and determined that the newer, non-socialite group could, indeed, take over the club, including the treasury of about $3,000, and the by-laws would not prevent that happening.)

|

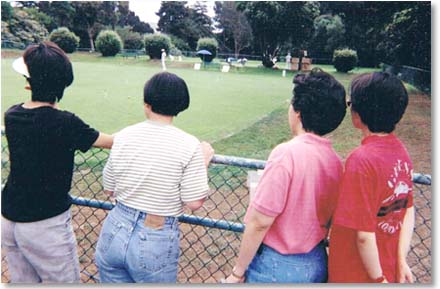

| Easy access is an essential factor in the success of public court croquet. Whenever there were people watching at the fence around the new courts, a member would usually approach and say, "We give free lessons on Saturdays," or invite them in to watch from the benches the club installed both inside and outside the fence. |

It looked like a power play of young upstarts, but at their meeting, they decided--Mike, Bob, the Chathams, John, Hans and the Berkeley bunch--that they would not "take over" the board all at once, but elect only two members to the five-person board in the next election: Hans and Mike. Bob would run for the board in the year after that.

|

| This photograph is pretty close to Bob's ideal self-image of the time: looking good in his Panama hat on Stern Grove's north lawn, and speaking with an air of calm authority. |

The group agreed that would be great, but it would never work, because as everyone knew at that time, croquet was a sport for the elite class--for rich people--so the City would not build courts for the San Francisco Croquet Club. (Jack Osborn had been tremendously successful in designing a development formula that appealed to wealthy and influential people--the people who could either build courts or get access to good lawns.) Bob said he'd like to try to get it done, and would they mind? No, they wouldn't mind.

Building America's first two-court club on public turf

Alman later wrote three volumes for the Croquet Foundation of America on how it happened. The short and mostly accurate version is that he found a champion within the park system, who turned out to be Barney Barron, the head of both Rec and Park, and kept going to his office until he agreed to talk seriously about helping yet another private club take root in the parks system. (There were more than 30, already, and only one of them--the lawn bowling club--had facilities expensive to build and maintain.)

The existence of the Lawn Bowling Club was important in those talks, as a point of comparison. It turned out that the bowlers contributed remarkably little to the City for what they got, their three lawns and clubhouse having been included as a central feature in the overall park design near the turn of the century as "the jewel of Golden Gate Park." That comparison was to be helpful in getting final approval in the vote of the Recreation and Parks Advisory Commission.

|

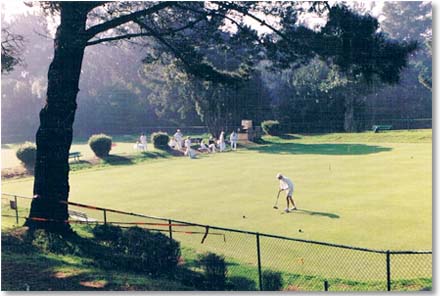

| This view of the new lawns approximates what could be seen from Highway One. Passersby could look down and say to themselves: "Croquet? I could do that!" The sheer visibility of a "public club" attracts the notice of many youngish and sporty players, who would become national and international champions of the sport. |

Once the basic conditions were established, the discussion quickly turned to an investigation of the entire park system--dozens of parks--to find a spot where a private club would yield benefits for the greater public; and to how, at Barney's suggestion, the financial participation of the club could provide greater flexibility for his own park and rec management.

The perfect spot turned out to be a neglected very public corner of Stern Grove--the second-biggest park in the city, with a full-time staff of eight and no year-round group for them to interact with. Two long-abandoned bowling lawns right below Highway One would have to be rebuilt with irrigation.

An essential part of the talk had concerned how the club could include in the plan specific public benefits justifying to the Recreation and Parks Advisory Commission (the voting authority on the proposal) to spend public money on public facilities for a "private" club. Among the many benefits to be given the city and the public--in addition to making that corner of Stern Grove active and attractive again--were an annual gift of cash, having club volunteers build much of the facility, a weekly free day for seniors, and benches and fencing to benefit the entire community.

The club would do the bulk of the labor if the City supplied the sand and the redwood compost required; the club would donate the fence and seating not only around the lawns but in the surrounding area and pledge $5,000 a year to the Friends of Recreation and Parks, providing Barron with a fund he could use to do small improvements around the parks without going through channels. The club would also donate to the city a free weekly Senior Day.

With Barron's support and his considerable coaching of Bob Alman and the club members enlisted to come to the hearings, the Commission delivered a unanimous vote of approval.

|

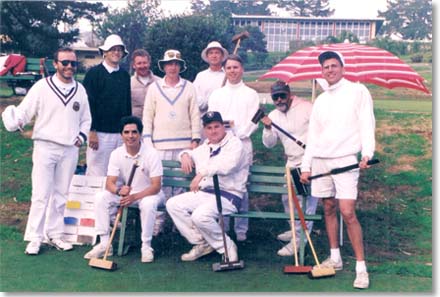

| This group picture must have been snapped in the early nineties, with visitors from Sonoma-Cutrer coming down, perhaps for either casual games or a singles tournament. (The Golden Gate Challenge Cup, an interclub team competition played with four doubles teams from each club, came much later.) Maybe Wayne Rodoni snapped the photo. |

John Taylor and Wayne Rodoni were especially helpful during the lawn-building process. Wayne designed and built the huge screeds used to level by hand each little segment of the lawn. But many members came out to level the sands, in the fall of 1985--a process which seemed endless.

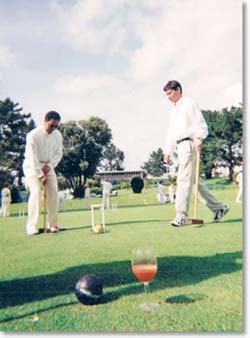

Publicity for the second annual San Francisco Open in 1986 had promised to produce the games on those two more-than-full-size courts (in addition to the old "hill course" nearby) but the grass was very slow to fill in. Nevertheless, Taylor came out and mowed the lawns for the first time with a push-behind on the day before the Open was to be begin, in May of 1986. So that Open was played on sandy but approximately level half-courts (which nobody complained about) and contested by many of the best players in the West.

One of Bob's lingering memories of that 2-flight event was defeating the USCA national champion Reid Fleming on a half court in the first round of the single-game Championship Finals knockout. Fleming was top seeded on the basis of his block record, and Bob was bottom-seeded. Bob had decided to take a wild "what the hell" shot early in the game, and it succeeded. The win embarrassed him, because Bob had no chance to win the tournament and he had knocked out Reid Fleming.

|

| Bob regards this photo as iconic, with an elderly lady approaching a young man to congratulate him as the shadows lengthen at the end of the tournament. This happens to be a Rodoni win over Margaret Chatham, his essential step into the Championship Flight on the way to becoming the club's first national champion. It's presumed to be a Dave Dondero photo. |

So players in the 1986 San Francisco Open did not complain about the half-courts. This was a much bigger tournament than the 1985 event had been, allowing for many more singles games to be played on three full-sized lawns. as well as a single-elimination doubles tournament. And although the lawns were bumpy and sandy, the competition was fierce, with many very good players present, including players from Arizona, whose Arizona Open had long been the major American Rules event in the West.

With the club's much greater visibility, two complete lawns just below Highway One, there would soon be many young and sporty guys and gals who looked down and said, "I think I could do this." It would mean the end of Mike and Bob's career as the best players around. Wayne Rodoni would soon be joined by John and Anne Taves, Jim Audas, Hans Peterson, Sal Esquivel, and other players who were becoming national champions in both Association Croquet and Jack Osborn's beloved American Rules.

|

| Private parties and corporate events were a vital part of the revenue needed to support the club, with the City getting at least half the revenues from each such event, and sometimes much more. The members who volunteered got "membership credits" calculated into the modest annual fee structure each year. Often, the club owed them money in addition to their membership fees.) |

By this time, Bob was running the San Francisco Croquet Club, without any office beyond board membership: organizing, promoting, writing, selling and running corporate and private events. The Saturday Introduction to Croquet was built entirely around Golf Croquet--a "California" version designed by Damon Bidencope, the pro at Meadowood. Bob was still in the local top rank of local players at the time. Rodoni had not yet perfected his game. Taves and Hanson had barely arrived.

But soon the SFCC was to be acknowledged as America's "club of champions," and Bob knew, at some level, that he would have to invest even more of his fragile ego into organization. In his own mind, the new motto of the club would be "Come to San Francisco and beat Bob Alman."

The last Annual Vision Meeting....beginning a long decline

Some of the "harmful things done" in the SFCC would not have to be attached to any particular person or given any sinister motive. They are perfectly reasonable things done in all innocence by a group of nice, well-meaning folks who really don't know any better. At some time in the early nineties, the SFCC board said, truthfully, "But Bob, we've done everything we wanted to do as a club, so why should we continue to have these annual VISION meetings.....?"

We had said we wanted two courts of our own. Done. We had wanted a big and prestigious annual Open of our own. Done We had wanted a big club with relatively low membership dues. Done. We had wanted to finance the club mostly with private parties and events. Done.

Bob believed that his Vision meetings were essential to the life of the club. But he also knew that explaining with any kind of reasoning would sound awfully "esty," so he didn't even try. He knew that when any organization stops creating a vision of its ideal future--and after that a list of concrete goals and planning strategies, somewhere next to go, something next to get done--it stops growing; and when it stops growing, it won't stand still, it will begin to decline.

He had done some very deep thinking to produce for Ellery McClatchy, long-time president of the Croquet Foundation of America and a silent benefactor of many, many people in American croquet, a three-volume Monograph Series on Club-Building, Organization and Management. It included such "esoterica" as The Vision. It was the first significant gesture of support Ellery would give to Bob, and it would turn into a long-term monthly stipend in the mid-nineties, justified by the creation and management of the first two significant croquet websites in America: the USCA website and Croquet World Online.

In his own mind, Bob has since dated the radical decline of the SFCC to that single board decision which eliminated the annual Vision Meetings, organized to invite all the club members to come together to create a future for which they could all be responsible. The timing does look strange, in retrospect. Membership had peaked at close to 100. And the SF Open was about to achieve maximum capacity every year with 64 players in three flights, seven courts available for play (including two in Oakland), and some of the club's best years yet to come--to be described in Part Three of this croquet memoir.

|

"Croquet Magazine" in three issues

Bob Alman and Mike Orgill more or less bonded with Hans Peterson when Hans and Mike started (on their own, they thought!) a black and white magazine. (The first issue, in 1987, features Mike Orgill's cover story about the creation and opening of the Sonoma-Cutrer courts, with Neil Spooner as director of croquet, and lists Bob Alman as a "consulting editor." Bob was reluctant to commit to editing a croquet magazine long-term....HA!) The second issue was the best, for content. Bob recalls organizing with Mike and Hans a multi-part lead story which remains an excellent and accurate description of the war between competing forms of the game in the last half of the 80's, told from many points of view, including interviews with the two opposing "generals." It was obvious to Bob and Mike that Stan Patmor's organization, The American Croquet Association, HQed at his house in Phoenix, would not prevail, because of his own laid-back lifestyle, character, and habits, and that Osborn would eventually prevail, because he was a survivor and a full-time monk in the service of his creation, the USCA. The founding impetus of the ACA was fair and just and necessary: to promote the play of the International Rules game in America, along with Osborn's beloved American rules. (What might Osborn have thought had he survived to see the unexpected rise of Golf Croquet, which in 2019 now far surpasses both American rules and Association Croquet?)

At the time, in the mid-80's, Bob recalls an SFCC board meeting which cast a very close vote--4 to 3, in fact-- to stay in the USCA when other western clubs were quitting that national organization. The argument for the SFCC staying in the USCA was this: "We don't need the USCA. But the USCA needs us. They will notice that, eventually." But Osborn at the time described us all as "Western Killers," and was genuinely concerned that we would prevent people joining organized croquet because we were insisting on "standards" for the sport, and especially the playing of the International game, which he was actively suppressing at the time. Osborn had already responded to Alman brusquely when he had proposed to Jack at the Arizona Open some ideas around "public court croquet." Jack had famously declared that croquet in America was "a sport for the elite class," and turned away on his heel. Later, when Bob called Jack's business in West Palm Beach to buy hoops with "tight settings", Osborn had shouted at the western upstart, "Don't you people want wickets wide enough for people to shoot through?" and slammed down the phone. Because of such comments and behavior, Osborn was ousted as USCA president. Some time after that he found out that he had cancer. Having never even been cordial to Bob--because Bob had been and still was the organizer and leader of the "San Francisco roughnecks"--Osborn telephoned a few weeks before he died, saying he was mending fences, and delivered to Bob in the course of a remarkable half hour a back-handed compliment that still brings a smile for it's totally Osbornian cast: "I always knew your intentions were good, Bob," he said. Bob was moved by the call, and by Osborn's intention to make a clean exit, after all. The obituary Bob Alman wrote on his life and death is accurate and balanced and the one chosen for Wikipedia's Jack Osborn entry. The third issue of CROQUET WORLD saw a redesign by our member Paul Curtin, who had created the SFCC logo. The magazine had "arrived" in concept, if not in execution, because we would never find or produce the black-and-white photographs that would make it the elegant black-and-white design that Paul's work deserved. The cover story was Guerilla Croquet--the 9-wicket game Mike and Bob had invented and played for many years and which was to be in the last five years of the century the official game of the USCA. We were thinking about the fourth issue of the magazine when Hans Peterson was arrested for dealing dope, as many of his fellow students at Berkeley and elsewhere in America were doing at the time. Hans was and is a great person and an extraordinarily capable one . After a years-long soap opera, he fully recovered his life and is now living with his second wife and fathering his own as well as his new wife's grown children. They don't permit in their house or in their presence the use of any kind of intoxicating substances. Hans is a dynamo in handling both ideas and execution. It should be no surprise to anyone that having settled into retirement in South Florida with his wife, Hans has inherited the presidency of the Sarasota County Croquet Club from its founder, Jackie Jones. Sarasota had replaced the SFCC with respect to size on public grounds in 2007, with three adjacent good courts for Sarasota County. That club has more than doubled its lawn space and is now deservedly the site of many regional and national events. Copies of the three issues of CROQUET MAGAZINE are now collectors items. |