|

Back to |

| The Front Page |

| People |

|

In memory of Neil Spooner |

||||||||||

|

by Rhys Thomas photos as attributed posted on August 8, 2019

|

||||||||||

|

||||||||||

At the time Neil Spooner was directing croquet at the most gloriously "private" facility on the West Coast in Sonoma County, just forty or so miles south, we were building the San Francisco Croquet Club, surely the most public of venues in the country. With the first World Croquet Championship being directed by Neil Spooner in May, we would surely benefit by scheduling next to it, giving the great overseas players something else to do in America, and building in a natural "power" base for our new event, which was to become a stronger tournament, over time, than the USCA national championships held in the East--not because of the international players but because of our own "Western Killers" who at the time were ranked at the top in American Rules, partly as a result of what Neil Spooner was doing in Sonoma County. Rhys Thomas was regular at both events and a closer observer of all this action.

Among many friends, I am lucky to have had four great mentors in croquet: C.B. Smith, who taught me the game; Tony Stephens, who taught me patience with the game; John Prince, who taught me to respect the game; and Neil Spooner, who taught me to love the game and, most of all, to find the humor in the game, no matter what the outcome.

Neil Edward Spooner was born January 13th, 1953 in Adelaide, Australia, where he lived most of his life. But for eight remarkable years, between 1987 and 1994, Neil lived in Northern California's wine country, where he organized and managed the world's premier croquet operation and the first recognized World Croquet Championship (WCC) at Brice Jones' Somona-Cutrer Vineyards.

|

| Neil Spooner graced the first issue of CROQUET MAGAZINE in 1986, on the court at Sonoma-Cutrer. |

A year later, Neil returned at Brice's invitation to play another Association Croquet exhibition at Sonoma-Cutrer--this time versus English champion Stephen Mulliner--in a precursor to what would become the World Croquet Championship. It was a thrilling back-and-forth match for all present, eventually won by Stephen with a game-ending triple peel.

Spooner is hired to run Sonoma-Cutrer's croquet

That was the beginning. Brice hired Neil almost on the spot to run his fledgling croquet operation and the World Croquet Championship took off in 1987. With Neil in charge, Sonoma-Cutrer quickly became the most desired croquet destination in the world, offering lucrative prizes to the winners, and earning millions of dollars for charity with its courtside high-end wine auction. Along with the world's best AC players, Neil always kept spots open for upcoming American players, who usually got trounced but learned so much in the process.

|

| Here is Neil Spooner in 1986, as we like to remember him, in his prime, delighted to be invited to America to direct croquet and ultimately the sport's first "world championships" at a sparkling new facility in Northern California we all called "Croquet Heaven." |

Neil was already a great and colorful croquet champion when he came to California, "He was one of the toughest opponents I played against," said John Prince. "I played Neil twice in the MacRobertson singles and he won both times in three games. He had great powers of concentration, could play immaculate breaks and produce a fantastic series of shots when it mattered most."

Neil could also be prickly, as Prince reluctantly remembers. "I often regret that my initial experience with him was rather negative. He was playing a singles in the 1974 MacRobertson World Teams against Roger Murfitt, who had to play with a totally foreign mallet (his having somehow disappeared off the bus in Los Angeles). Neil was game up and easily winning the second. Alan Anderson and I went over to offer Roger a bit of support and Neil went for us, accusing us of giving advice and telling us that we should not be talking to Roger. Not sure how we responded, but he turned it around and said 'We're not allowed to talk to anyone during a match in Australia.' We told him we weren't in Australia. So we didn't start off well."

|

| This photo from the 1986 Australian Croquet Gazette includes Barrie Chambers, Neil's favorite partner. |

The first time I saw Neil play was at the 1989 Meadowood Classic, the last great American Rules Doubles Tournament. There were sizable cash prizes and lavish entertaining at Bill Harlan's exquisite resort tucked among the vineyards along the Silverado Trail just east of St. Helena. All the world's best players eagerly showed up, including Neil and his Aussie mate, Barrie Chambers, who were the defending champions, having won the tournament and $6,500 the year before. I was there partnering with C.B. Smith in my first big-time tournament.

Neil entertains in on-court competition

Before the games began, Bidencope, Meadowood's croquet director and tournament manager at the time, informed all the players that the club's custom stainless steel "super" hoops (the original version) would be set to "zero tolerance," meaning they would be gauged to the exact diameter of a croquet ball. There were grumblings about that, but given the money stakes and the relative ease of Meadowood's perfectly groomed lawns, tight hoops were the only defense against the world's best players simply running the courts at will. A further instruction was that if a ball became jammed in the jaws of a hoop there would be no replay; we were to play it "where it lies."

The first test of this policy came when Neil approached hoop #2 in an early game of the tournament. C.B. and I were watching from the sidelines, waiting for our first start. C.B. regarded Neil as the greatest player in the American game and often told me to pay particular attention to his tactics. We watched Neil carefully stalk what looked like a reasonably short, straight-on hoop shot. Playing with his distinctive style and intense focus, he took a steady, smooth swing with his signature, flat-bottomed barrel-head Dawson mallet. The ball rolled firmly into the jaws, and then up the jaws, where it stuck solidly about six inches off the ground. And did not move.

The ball hung there between the uprights for what in memory seemed like an eternity, enough time for Neil to say loudly enough for all present on the Meadowood lawns to hear, "What am I supposed to do now? I can't play it where it lies because it's not lying anywhere. It's up in the air!"

As Damon recalls, there was a pointed discussion between the two. Neil wasn't happy and Damon wasn't budging from the tournament rules. While their debate carried on, the ball began to roll down, ever so slowly and almost comically. It took at least a minute to finally make it back to the ground. What followed soon after was an emphatic backwards hammer shot by Neil that screamed through the hoop and bounced so high that it cleared the courtside railing and went sailing down the 9th fairway of Meadowood's golf course.

"I believe he was expressing non-verbal communication and his opinion to me and anyone that cared to pay attention regarding the emergency rule in use at that event," Damon said. "At that point we had fully expressed our opinions so there was not much else to be said." (The emergency rule stated no "crush" would be called on a ball wedged in a hoop.)

John Prince recalls the many sides of Spooner

Neil could be feisty and fierce on the court and then an incredible sportsman and humble gentleman off it. "He and Theresa (Neil's wife at the time) were very kind and took Sue and me to San Francisco for dinner during the Sonoma tournament," remembers Prince. "Much later we sat together at an old-timers dinner at Adelaide during the 2012 World Champs. He totally surprised me by saying he had been told about me from my debut in the 1963 MacRob and I'd been an inspiration and goal to play against when he was starting out."

Neil had his demons, no doubt. John Prince told me this: "Having dealt myself with a series of childhood traumas a few years later in therapy I have wondered about Neil, his rage, his hatred of authority, his self-sabotage and punishment. If I knew way back what I learnt years later I'm sure we could have been good friends."

|

| C.B. Smith and Neil Spooner meet on Sonoma-Cutrer's lawns at the 1985 USCA Western Regional. If you look closely, there appears to be money changing hands. A bet, maybe? |

Mastering the American Rules game

While it was his Association Croquet reputation that brought him to Sonoma-Cutrer, it was the American game that really captured Neil's attention and imagination. He quickly became a fixture on the West Coast tournament circuit, showcasing his enormous talent and cunning inventiveness on the courts. "He was an excellent teacher and a brilliant croquet strategist, a genius in his field," Orgill said."

Along with his superb wit and friendly demeanor, Neil loved to talk strategy and tactics with others, especially the upcoming crop of American players that he mentored. And there were many of us who soon became his devoted disciples and prot�g�s. At Sonoma-Cutrer and the tournaments he traveled to around the country, Neil always shared his knowledge and encouraged us in every way to become better players. As I wrote in a sidebar to his engaging three-part croquet memoir, no one was better sideline company at a tournament than Neil Spooner.

But when it came time to play a game, Neil was the cat and his opponent was the mouse. He'd get this grin on his face and a bright twinkle in his light blue eyes. He loved to stalk and pounce. For all his great success in the Association code, Neil truly loved the American rules. And he took advantage of them. "He deconstructed the American rules in ways that the American exponents had never imagined," Orgill said.

Neil once told me to read the rulebook before every tournament. Even if you thought you already knew the rules, something might come up. "If you know all the rules and the loopholes," Neil once told me, "you have an advantage." Among his many novel tactics, Neil revolutionized the opening sequence of the American game using what became known as "The Chernobyl Open"--deliberately declining to have your ball pass through the first hoop and thus become eligible for the roquet/croquet and bonus strokes. Garth Eliassen of the now-defunct National Croquet Calendar coined the name, but Neil was the true author.

The "out game" existed long before Neil showed up in America, usually after botched opening shots. Archie Burchfield was a master at the "out game" but, as he once told me, he only played the out game because he missed his first shots too often. Neil, he said, played it on purpose.

Neil used the out game in American Rules as a strategy, deliberately choosing to go second to hold out the Yellow ball (last in the opening rotation). His Red ball became the hunter, going after the opponent's Blue to feed to Yellow. He even found an obscure loophole in an early version of the rules: If an "out-ball" shot to the exact spot of a ball already in the game, that "in-ball" had to be moved one yard in front of 2-Back, right there waiting for Neil's out-ball to come through number 1, giving him an immediate advantage. Once exposed and exploited by Neil, the rule was later changed.

Neil's out-ball tactics were cunning and superb. Playing with masterly perfection, he found great delight in winning American games by scores of 26-1 and 26-0, later to be named the "Half Spooner" and "Full Spooner," names that stick in homage to this day. Many of us learned to play the out-ball game from Neil, including C.B. and the late Mik Mehas, who effectively used it in nearly every tournament game he played.

|

| Neil targeting a roquet with his distinctive shooting style. |

At the 1989 Arizona Open, an American Rules tournament, Neil and future Association Croquet world champion Reg Bamford played in the final. Reg was way ahead going into last turn and looked certain to win, having left a "killer" leave. But it was never over until it's over with Neil. "He hit a 30-yard 'last shot' on a semi-wired ball on the 9-inch boundary against me in the final of the Arizona Open!" Reg recalled. Neil went around, pegged out the hot ball. Reg never shot again and Neil won his second straight Arizona singles title.

Competing and winning in the best tournaments

Neil loved playing in the Arizona Open. It was a respite from his croquet and winery duties at Sonoma-Cutrer and offered some of the best competition and convivial hospitality in the croquet world. John and Nelga Young were always there, along with venerable USCA champions John Osborn and Teddy Prentis, making it a true national class tournament. In one of the more unique formats, it kept championship and amateur flights together in the block play, with the "A's" playing the "B's" in the opening rounds.

In 1991 a wide-eyed and grinning yet clearly green Doug Grimsley, a retired tuna boat captain, showed up with a backyard short-handled barrel-head mallet to play in his very first croquet tournament. And his very first game was against the tournament's top seed, Neil Spooner.

"I lost the toss and he elected to go second," Doug vividly remembers. "I asked several times if he would go first. He was upset until he realized I didn't know ANYTHING!"

Once Neil figured out he was playing a complete novice with absolutely no knowledge of the rules, he showed Doug where to put his ball and how to start an American croquet game.

"I stuffed the first shot of my croquet career," Doug said. "He jumped in. I stuffed again and he jumped in with his second shot. It was after the second successful jump that I felt the game slipping away." Neil won 26-2 and Doug, who has gone on to win nine USCA national titles, had his initiation to croquet, and to Neil.

The Arizona Open was the site of many of Neil's croquet accomplishments in America, including a rare three-ball triple peel which he ran against me in 1991 after I was foolish enough to ask him if anyone had ever accomplished that feat in American Rules. He did that twice in his American Rules career.

|

| The super-competitive 1993 CalZona at Sherwood Country Club was played by Back Row: Don Fournier Jr., Jim Bast, Charlie Smith, Rory Kelley. Front Row: Erv Peterson (holding Trophy), Rhys Thomas, Neil Spooner, Ren Kraft, Patty Dole, Bob "Rebo" Rebuschatis, Wayne Rodoni, Ed Cline. |

Neil's time in California came to an abrupt end in 1994 due to what people in Hollywood call "creative differences." But he left his indelible mark. "We first saw him after his form had peaked and he was on the slow downslope," Orgill said, "but he had been one of the best, most natural croquet players in the world. He didn't practice much, he'd done enough of that, and there was little incentive for him. He beat all of us all the time to prove it. I think leaving Sonoma-Cutrer broke his heart."

I had lunch with Neil and his family the day before he left California forever. Typical of him, he looked to the future, not to the past and why he felt compelled to leave. Few of us knew we'd never see him again.

I was fortunate to keep in touch with Neil over the years. In 2005, when WCF Secretary-General Brian Storey asked me to form a WCF Hall of Fame selection committee, Neil was my first pick, along with John Prince, Archie Peck and Bernard Neal. For the next six years I administered the committee and had the pleasure of reading the discussions and deliberations of these giants of croquet. Neil's contributions were always rich with his knowledge of the game's history, honest, direct and usually laced with his trademark sense of wry humor. In 2010 it was my honor to nominate Neil to the WCF Hall of Fame.

|

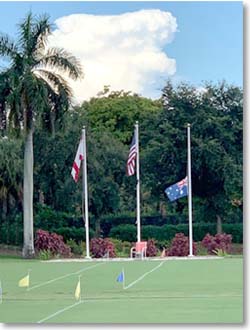

| At the National Croquet Center in West Palm Beach, the Australian flag was fixed at half-mast the week of Spooner's demise. Spooner's mallet is on permanent display in the trophy hall. Photo by Hal Denton. |

Whether any of today's top flight players know it or not, Neil Spooner was singularly responsible for elevating the American game to where it is today. He was the one who spearheaded use of the "rout" (croqueting partner out of bounds next to opponent's cold ball while positioning striker at pioneer). He championed the idea that you don't need to go dead to set up a break for partner; he built AC-style breaks with the initial attack. And he did it time and again, showing us all how to do it.

His students quickly became the best players in America, winning many titles, causing Jack Osborn to label us the "West Coast Killers." Neil opened up the game in a way nobody had before. He taught us not to fear deadness, but to embrace it, because there's always special relief, at least in American croquet.

Sadly, there is no such relief in life. Neil Spooner passed away at 3:03 in the Australian morning of July 22nd, 2019. He was 66 years old. He leaves behind his son, Daniel, and daughter Samantha, both born in America, and three grand-daughters, Evie, Aria and Zara.

Today, you can find Neil's trademark Dawson mallet in the trophy case at the National Croquet Center in West Palm Beach. It's the round-headed one with "Spooner" on it.

Rest in peace, Neil. We miss you.

|

Neil the Competitor

By Bob "Rebo" Rebuschatis I met Neil Spooner when we both worked at Sonoma-Cutrer Vineyards. Back in the day he was the director of croquet and also worked in accounting at the winery office. He was a soft-spoken, humble guy for sure. For example, you had to learn that he was the Australian national croquet champion from someone else; Neil would never tell you himself. At the time we met I knew nothing about big-time croquet. But over a few months Neil and I became friends and he started teaching me the game on the Cutrer lawns after work. Later on, when I learned the game well enough, Neil and I started playing games rather than just making shots and running hoops. It didn't appear he was pushing himself very hard during our games and they were most always one-sided consisting of me sitting on the wall watching him play and run hoops with that little short backswing stroke of his. Occasionally, as time went by, I would give him a little challenge. When that happened he would run the table on me and finish things off without my getting a chance to get back on the lawn. We became close friends, and he promoted me in the game and cheered me on against my competitors. And then one day in a tournament we came up against each other. Surprisingly, I got out ahead of him and it looked like I would have a chance to possibly win. I set the lawn and walked off as Neil came on to take his turn. I expected a friendly wink of the eye from him and a comment something like "nice going." Instead what I got was a hard look and a comment straight out of Caddyshack when Rodney Dangerfield tells Judge Smails, "While we're young." I guess I was playing too slow and too successfully and it got under the skin of the master. It was clear to me then that Neil was not interested in losing, even to his friend. So when it came to competition on the croquet court he was a fierce competitor, way more so than I had realized. Of course, in that game, he ran his ball around. set a difficult leave and finished me off in two turns. When he wanted to be, Neil was the best croquet player I ever saw. And one of the best friends I've ever had. I will miss him greatly.

|

Rhys Thomas has been a player, manager, administrator and referee in the realm of championship croquet for more than 30 years. During that time he has mastered the keen ability to stuff hoops and miss short roquets at critical moments with uncanny precision, allowing him ample time on the sidelines to contemplate the folly of his chosen profession, which is writing. He is the author of five books and hundreds of hours of documentary films. Rhys lives in Los Angeles with his wife, Michelle, and three cats.