|

Back to |

| The Front Page |

| News & Features |

|

Finding a home for the croquet collection |

|

by David Drazin photographs by Lara Swimmer Photography Posted October 24, 2009

|

No single author has contributed more to the cyber-pages of CROQUET WORLD than Dr. David Drazin, who over a decade has penned many historical articles based largely on the primary source materials he, himself, collected and stored in his extensive home library. True to character, he cheerfully accepted our invitation to produce a detailed firsthand account of how he searched for and finally found the perfect permanent repository for the 2,000 items now and forevermore to be known as The David and Anne Drazin Croquet Collection, half a world away from his home in England - at the University of British Columbia.

I started collecting croquet books in September 1992. My elder brother Michael, an omnivorous collector, who as a confirmed bachelor had built his home as a museum in West Lafayette, Indiana, many years previously, was over here in the UK on sabbatical leave from Purdue University and could not understand how, as a committed croquet enthusiast, I had not got any books about it to speak of. So I was shamed into action.

To begin with, I just thrashed around, collecting all and sundry. But one thing soon led to another and within a matter of months a focus asserted itself: I was collecting print material about any aspect of croquet, or merely with reference to it, including books and pamphlets, shoes and ships and sealing wax, articles in newspapers and periodicals, in fact any print material in any language that could have any bearing on the game. The only exception I made from the start was the very large body of specialist serial literature, chiefly periodicals issued by clubs and international, national, and regional associations. I had enumerated about 60 such journals, and it was obvious that there was no way I could collect and find space for every issue of each one.

The first challenge: finding the right focus

So things continued much in this way for a few years, while I got into bibliography, learnt the rudiments of document storage, established relationships with bookbinders and paper restorers, and built a management database to record my wants and acquisitions. But as year followed year it became increasingly evident that I had bitten off more than I could chew. There was just too much literature to enumerate, control, acquire, and record with the resources I was able and willing to devote to these tasks. I needed to simplify.

First, I ceased collecting the non-specialist serial literature, then fiction, biography, and belles lęttres, then works of nonfiction about non-sporting subjects, then books and pamphlets principally about other sports and pastimes. These items I sold to other specialized collectors or gave to museums, libraries, or croquet organizations. The residual material - which came to form the core of the Drazin collection - consisted of books and pamphlets chiefly about croquet, or including the word 'croquet', or its equivalent in another language, in the sense of a ball game related to the game of croquet as presently understood, on the title page. I also included croquet journals issued no more frequently than once annually.

Inevitably this definition has an arbitrary quality. But at least it has the merit that items so defined will be found by entering the word 'croquet', or its equivalent in another language, in any popular search engine.

As it happens, my entire collection was gifted to the University of British Columbia Library in March 2009, long after I had stopped collecting titles in the foregoing categories but including items in those categories I had already acquired. So the collection has a curiously patchy character: the core of the collection, comprising specialist literature about croquet, though by no means complete, has a palpably ultimate quality, whereas other categories are grossly underrepresented, some wanting several very well-known titles.

|

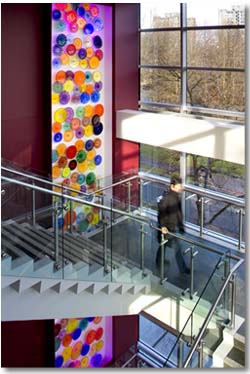

| The Drazin collection is housed in the University of British Columbia Library’s Rare Books and Special Collections division, in the Irving K Barber Learning Centre. This is a sun-drenched view of the Centre's west entrance. |

Not long after I started collecting, my mind turned to finding a long-term home. Until quite recently I imagined that on my death my executors would sell the collection, maybe at a lucrative premium, that my family would benefit from its sale under my will, and that it would be received intact as a complete collection by a well recognized institution with unimpeachable curatorial resources which would make its contents available to scholars worldwide. Of course, someone would have to fund the exercise, and here I imagined that a wealthy private sponsor or well funded institution could be found without too much difficulty. My mind then turned to targeting a potential host institution.

The search begins in the UK and USA

Two possibilities came immediately to mind - the British Library and the Redwood Library and Athenæum in Newport, Rhode Island: the former in consequence of time I had spent there, the latter at the suggestion of my friend George Herrick, a local croquet enthusiast, who was then on the Redwood board of directors. So I made it my business to cultivate both institutions, getting to know Tom French, the Head of Modern British Collections at the British Library, and Cheryl Helms, Director of the Redwood.

The British Library was a national institution with impeccable credentials, and the Redwood was housed in the oldest library building in continuous use in the United States, located next door to the National Croquet Gallery and almost next door to the International Tennis Hall of Fame at the Newport Casino, venue of the 1992 World Croquet Championship.

|

| The luminous atrium inside the Learning Centre’s west entrance. |

In January of the following years I sent both institutions updated catalogues of the collection, specifying the condition of every item. Tom French saw the collection, was impressed by how it complemented the British Library's holdings, and offered much general encouragement, though observing a conflict with the Library's general policy of stocking no more than a single copy of any book, and rather glossing over the issue of funding; while Cheryl Helms, who never saw the collection, was at pains to get across the point that her main job, as that of any head librarian, a task at which she excelled, was to find sponsors to fund the acquisition of new material.

An important reserve scheme, which appeared to offer reasonable assurance of funding to the British Library, was 'Acceptance in Lieu', operated by Her Majesty's Revenue & Customs. On the taxpayer's death, HM Revenue & Customs would, on satisfaction of certain conditions, accept the value of a 'preeminent' heritage item in lieu of payment of capital taxes plus a 'douceur' of 25 per cent as an incentive. My family might not receive the full value of the collection, but at least they would receive the douceur and would be spared its charge to capital taxes.

However, Acceptance in Lieu posed problems. It only kicked in on the death of the donor. In the ordinary course of affairs, his executors would have to do battle with the HM Revenue & Customs, the host institution, and the body that would evaluate the 'preeminence' of the putative heritage item. These were significant hurdles, and there was no guarantee that they could or would be successfully cleared.

A consequential choice: sell or donate?

On the understanding, nevertheless, that I had done enough during my lifetime to ensure a reasonably smooth transfer of the collection's ownership on my death, during the next few years I gave the question of ultimate disposal less attention, just occasionally updating a precatory letter to my executors to ease their task of transferring its ownership to a worthy institution when I had gone.

But as year followed year, I got the feeling that times were changing, that the burdens of curatorial responsibility carried by institutional libraries were slowly outstripping their interest in acquiring new collections. Tom French's successors at the British Library displayed much less interest in the collection, apparently due in part to its overlapping the Library's holdings and its containing so much material published in countries outside the United Kingdom. And I began to wonder about the Redwood Library and Athenćum. While I could count on the steadfastness of the then Director, what of her successors? And however venerable its past and present, in future years would its resources keep pace with the increasing demands of information technology and a widely scattered target audience?

As a result of several contacts made in 2006, I was rather turned off by the notion of settling my collection in a major institution. The head of the Rare Book & Special Collections Division of the Library of Congress in Washington, DC, did not even bother to reply to my inquiry, even after I had spoken on the phone with a qualified member of his staff; the British Library seemed to lose interest in consequence of reservations previously expressed; and I had serious doubts about other legal deposit libraries in the UK, notably the Bodleian Library in Oxford, which had obvious claims but which I thought lacking in interest and resources.

Exploring the auction route

The successful sale in April 2005 by Dominic Winter Book Auctions of books about croquet collected by David Prichard marked a new turn in my thinking. It struck me that most lots made good prices and vitally, as far as I could tell, they all went to croquet enthusiasts who could be relied on to cherish them during their lifetime and pass them on, very likely by sale at auction, to the next generation on their demise. If I was to follow the example of the Prichard family, though failing to preserve my treasures as a collection bearing my name, perhaps I would succeed in doing right by my family and the croquet fraternity. So I looked into the mechanics of sales by auction.

What I found left much to be desired. The two substantial sales of sports literature I knew about from the inside - the David Prichard croquet collection and the important angling collection of a friend sold by Bloomsbury Book Auctions in 2003 - were not strictly comparable in that the vendors were experts in their fields whereas my family had little knowledge of or interest in croquet or the antiquarian book trade. Moreover, these two sales I knew about were small, all lots being exposed to lively competition, whereas mine was much larger and included titles represented by several variants, which might not arouse such competition in a single sale.

My doubts were strengthened if not confirmed by points raised by Bloomsbury Book Auctions when I consulted their managing director after their angling sale. They would prepare a glossy brochure which would itself preserve the memory of my personal association with the collection, and much would depend upon how the separate lots were formed. In the case of a title represented by several variants, the whole set would first be offered with a reserve, and if the reserve was not realized, each variant would be offered for sale as a separate lot.

Such representations made me wonder. A sale or sales could be more or less successful. And while the auction house would doubtless be well satisfied in any event, would my executors? Much might depend on how the collection was divided into lots, on how well the catalogue was researched and presented and, most critically in a relatively thin market, on how many sales were staged over what period of time. Here there could be a conflict between the interests of the vendor and those of the auction house. The auction house would presumably want to stage the sale over a short period, perhaps as a single event, whereas the vendor might reasonably prefer to stage the sale over a longer period of time. Unavoidably, the balance of expertise would lie with the auction house.

The benefits of gifting

The thought of gifting my collection, rather than selling it, was first put in my head in 2005 by my friend Tremaine Arkley. Planning to settle a collection of artwork including illustrated books about croquet in the Rare Books and Special Collections division of the Library of the University of British Columbia in Vancouver, Canada, he asked me to value a number of items. In 1976 his parents had donated a collection of children's literature to the Library, and the Library had recently received a very substantial endowment from Irving K. Barber and was negotiating the acquisition of an important collection of golf literature. So I was delighted to receive a visit from Shakeela Begum, Director of Development of the Library.

|

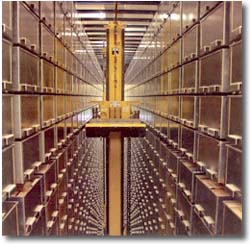

| The automated storage and retrieval system (ASRS) can house more than 1.5 million items in an environmentally controlled system. The ASRS is the first such state-of-the-art Canadian library installation and the largest in North America. Robotic cranes can retrieve materials rapidly from more than 19,000 bins distributed along four aisles. |

There is no substitute for personal contact. In no time at all Shakeela made me feel comfortable with the prospect of gifting my collection to a library in a remote part of the world with scant croquet connection. Powerful selling points were an impressive automated storage and retrieval system, then the largest in North America, a commitment to sports literature, familiarity with modern means of communication serving the needs of scholars worldwide, and association with the Arkley croquet collection. And another thought struck home: the head of Rare Books and Special Collections noted that, however I might assist in the development of my collection after gifting it to the Library, it would necessarily be 'time-limited'. My age being in the upper seventies, the collection could only have a little way to go during my lifetime.

It just so happened that it was timely to review my family estate management arrangements. This I did in consultation with the head of the Tax, Trust & Probate department of a local firm of solicitors. He had some experience in the disposal of heritage items and was in contact with an expert in the field. In order to secure guaranteed exemption from capital taxes, I would need to gift my collection to a UK registered charity in my lifetime (rather than bequeath it in my will), obtain an undertaking from the recipient that it would be put to public benefit, and demonstrate that I had delivered it to the charity.

|

| The Chapman Learning Commons, on level three of the Learning Centre. This space is part of the restored core of the building that once served as the historic 1925 Main Library. |

Fortunately, possibly in recognition of the taxation constraints of would-be UK donors, the university had registered a charity in the UK, The UK Foundation of the University of British Columbia. I had received a draft deed of donation from the Library, and it seemed sensible that my solicitor should handle the negotiations directly, and he agreed to produce a first draft deed.

There followed something of a hiccup. On the Library's side, the negotiations were being handled by their in-house counsel, and it seemed to us that they did not appreciate my essential requirements. They returned the draft deed with proposed variations we could not accept. They wanted me to give my collection to the UK Foundation on the basis that the Foundation would require the UBC Library to make the collection available for viewing by the public. But that would fail to satisfy the condition that the charity itself should be contractually bound to ensure that the collection was available for public viewing.

But all's well that ends well. The Library then put the negotiations in the hands of a UK solicitor and everything was somehow sorted out. In default of agreement to the contrary, the collection would be called the David Drazin Croquet Collection, it would be catalogued by the UBC Library using the Library of Congress cataloguing rules, the UK Foundation would use its best endeavours to develop it, and would maintain it in its entirety as one collection for at least 100 years. And thereto we plighted our troth. (It was only after the event that we thought it fitting to add my wife's name to the official designation of the collection.)

Execution of the deed was held up pending clearance of an export license and then at last the deed was done. So the collection should soon be accessible in Vancouver, along with the Arkley Croquet Collection, and perhaps other collections too with croquet reference in future years.

|

| This stairwell features Belle Verre, a striking glass artwork by Vancouver artist Jeff Burnette. |

My sadness at losing a part of my life is relieved by the knowledge that the collection is now in safe hands, that it will be housed in a controlled environment, that it will be maintained professionally, that it will be made accessible to scholars worldwide for the foreseeable future, and that it will not be a charge to capital taxes, nor a burden on my family or executors. The loss of the collection will prevent my referring at will to pages of its contents, and will thus complicate the preparation of the final edition of my work Croquet: A Bibliography, but that problem will not be of major concern.

My work on this collection is well completed: It not only has a home, but the best possible home, with the best of care, in perpetuity.

|

HOW TO PACK AND SHIP A COLLECTION WITHOUT MISHAP

Location is critical: if you are going to offer a competitive quotation, you've got to be able to deploy specialist staff economically, and almost invariably that means they should be near at hand. The agents selected to handle my collection, commissioned by the lawyers acting for the associated UK Foundation of the University of British Columbia, specialists in the handling of books and pamphlets, duly arrived by appointment one morning from Watford, the nearest town to mine of any size. They completed their business with exemplary efficiency in two hours flat. Having done their homework, they had arrived with the right number of sturdy cardboard crates, all good stuff, having learnt from bitter experience that only the best would do. There's no point in saving costs if you can't deliver the product in the condition in which you packed it. The husband-and-wife team, George and Sindy, worked efficiently to fill each crate precisely, labeling them consistently with the collection database, ensuring that the contents of every crate could be easily identified by the University archivists. Sindy wore white gloves, to protect her hands from dusty bindings and the books from perspiration. There were no accidents or mishaps of any kind. The following morning everything was ready for transportation by ship. Any remaining crevices in the crates had been filled with polystyrene beads to prevent movement, they had been sealed, shrink-wrapped, and palletized, so the whole could be loaded mechanically into a standard container and delivered in the same state to the Library consignee. Bon voyage to the David Drazin Croquet Collection! - David Drazin |