|

Back to |

| The Front Page |

| People |

|

The Nigel Aspinall interview by Neil Williams Posted August 2, 1999 |

In the third of a continuing series of interview with croquet legends published in The Croquet Gazette, Neil Williams asks Aspinall the obligatory questions and some more besides: how he rates his peers; how one becomes a champion; what the Association game could usefully borrow from America in his "mid-Atlantic rules": and how you know when it's time to quit after two decades at the top to give a newer player a shot at being hailed as the best in the sport.

Nigel Aspinall and I meet at Roehampton, his home club, where he plays

tennis and golf and - but only occasionally - croquet. He gave up

competitive play four years ago. We talk in the Garden Room while down below

the October (1998) End-of-Season tournament progresses on those perfect

lawns.

Nigel Aspinall and I meet at Roehampton, his home club, where he plays

tennis and golf and - but only occasionally - croquet. He gave up

competitive play four years ago. We talk in the Garden Room while down below

the October (1998) End-of-Season tournament progresses on those perfect

lawns.

Nigel's rise to the top was nothing short of spectacular. Arriving as a new member at the Bristol club in 1965 at the age of 19 or so (he was an undergraduate at Bristol university), he was given a handicap of six. He had, he explained, played a bit at home from the age of 12 or so. His father had bought a second-hand croquet set, and the family had played on a former grass tennis court - despite two Victoria plum trees. They made up their own rules.

In Bristol he discovered the real game. "I could," he says, "hit one ball on to another, at, say, 10 or 15 yards, and I think I had a basic idea of tactics. But I was playing roll shots inaccurately, and I think I was still playing the sequence game."

A few weeks after arriving at Bristol his handicap was reduced to 3. He had time before the end of the season for a weekend tournament at Cheltenham and a visit to Parkstone in September. Next season, with a handicap of 1, he played in the Opens at the suggestion of a fellow club member, John Simon. Together, they won the Doubles. Both were then picked for the President's Cup, and Aspinall came joint second to William Ormerod.

He had gone from first tournament to President's Cup in 10 months.

There were no lessons on the way. All he did was ask a few questions. "You pick it up like that, really." Neither did he ever enjoy the luxury of fistfuls of bisques.

The record books show that, having risen to the top so effortlessly, he stayed there for over 20 years. In that time he won the Men's twice, the Open eight times and the President's an unequalled 11 times. In one particularly purple patch he won the Open four times in a row, and he won four President's back to back. He played in the MacRobertson Shield four times, from 1969 to 1986. Remember, too, that when he wasn't actually winning championships, he was usually runner-up.

I can see why Prichard in his The History of Croquet calls Nigel a "practical, match-winning machine," and I put it to him that he was more or less unbeatable for some years. "No," he says, "not quite unbeatable. No. There were all sorts of people who would occasionally beat me, and equally there were one or two people who found me - um - difficult."

So what, I ask, is the key to success? "I think I had the ability to concentrate very well. If you are concentrating 100% it takes wild horses to drag you off your stride."

Another quality also emerges: self-belief. And as we talk about John Solomon - the player who gains the greatest praise from Aspinall - one technical factor must be added to the list: "naturalness" of swing, a quality which both he and Solomon showed to perfection.

"Solomon was the best, I reckon. He had the most titles and perhaps the most natural swing. But Hicks and Cotter were very close to him. It's also interesting to see that on the three occasions when Cotter and Solomon tied for first place in the President's, Cotter won all three play-offs."

When I ask about his own first championship game (in 1966) Nigel recalls that it was against Humphrey Hicks, and the memory remains sharp. Nigel had "sailed away" with the first game, and in the second was well on the way to victory, having pegged Hicks out. The great man then hit what Nigel was sure was a wired ball and finished the game.

It would be interesting to hear various views now on how the third game should have been approached. What actually happened was this:

"The third game started just like the second. He was for 4-back and peg before I'd scarcely started. And again I hit the last lift. And again I thought, "Right, I should have won that second game." So I went round and pegged him out again. And in fact I did a whole lot better, and it was only because I got hampered at Rover...."

Nigel pauses here. He can still see the position, after all those years, etched on his memory.

"Wretched ball. And there was no way of playing even a fairly sensible shot. The best thing I could do was retire to a neutral corner. Hicks hit a nine-yard shot from baulk, and since by then Rover was his hoop, too, he won the game."

He thinks he was at his peak round about 1975, when from the end of 1974 to 1976 he won 24 consecutive games in the President's. "I'd won some in '74, all in '75 and the first five or six in '76. It was Colin Prichard who broke my run."

Nigel tells me he believes in practising "a little", and he offers this advice on the subject: "Try to make it exciting. For example, I have a routine of six-yard roquets, where you put four balls in a line and another four parallel six yards away, and the idea is that you hit as many consecutive shots as possible. Say you hit three in a row and then miss. You then have to zero your counter and start again. But this time - say a week later - you have to improve on three. As soon as you do, stop. Don't let it become boring. In other words, give yourself a target and improve on it."

I mention that John Solomon sees the biggest single improvement in the game as being in the one-ball shots, particularly hitting-in. "Well, perhaps, but he was pretty good at that himself, and I'm wondering really whether the margin, the percentage of improvement has been all that noticeable - scarcely measurable. I'm not sure I agree with him."

I ask why he gave up top-level play and learn that he was diagnosed as having dangerously high blood pressure, "And I reckoned it wasn't a good idea to increase the stress levels." Nigel then goes on to describe as movingly as John Solomon has done how his play was "going down hill anyway."

It wasn't that he felt the next generation breathing down his neck, but rather, "It was more in myself. Confronted with a two-yard hoop or even closer, your brain wants to do it but in the backswing something happens.'

And he describes the doubts setting in when faced with a cut rush or a 3-yard roquet. His mother, he tells me, was a very good pianist and teacher, but when she developed arthritic fingers she couldn't bear to play 'at a reduced level.' Rather than do that, she stopped altogether.

|

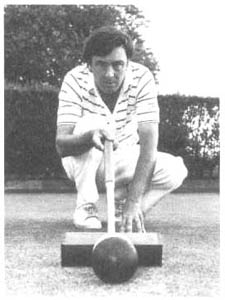

| Aspinall in play during the Granada TV final in 1986. |

"I think it will stay largely static. It is a bit of an esoteric game if you stand back and look at it with very plain, simple eyes. It's an odd game also as far as TV is concerned, because if you stop and think about it, it's shrouded in secrecy.

"To start with, the hoops are not numbered. If they were numbered, the viewer would be able to see where the next hoop was just from the picture, and therefore have an idea where the striker was proceeding. But the hoops are not numbered, and, in addition, the clip is hidden away during a break. I'm really putting myself in the shoes of the new viewer [or the casual spectator at any demonstration or recruitment event], who comes to it and thinks, 'What on earth is going on here?'

"And the clip is put on only at the end of the turn. And, of course, there's no score board. So the viewer coming to the TV screen doesn't know the score, doesn't know who's ahead. Doesn't know anything. It's shrouded in secrecy. It really is."

Staying with this theme of the future of croquet, I am keen to hear Nigel's views on the range of new versions of the game. Does he see them as a false trail?

"Yes, I do. And it's partly for that reason that I shall never support the idea of Advanced play in Handicap games, or bisques in Advanced games."

So are there changes he would like to see in croquet.?

"Oh yes. My mid-Atlantic rules. I'd like to borrow a couple of things from the American rules. For championship level players - say handicaps 1 or 2 and better - I would like to add two rules. The first is: if you run a hoop and your ball goes off, your turn ends. Second, if you rush or roquet a ball over the line, your turn would also end, except in the first stroke of the turn.

"So, for example, you can make a hit-in, or you can hit your own or an enemy ball off and over the boundary. But the idea of sending the ball over the line at any other time lacks subtlety, and there isn't really any need to do it. I think that would add an extra bit of difficulty and control.

"And I think it would have a further point: it would give the out-player an opportunity to be a bit more defensive. He can put a ball in a corner, but at present it's not too difficult to get it out - especially if you are allowed to rush a ball into the corner without any touch or control."

It seems fitting to end our conversation with those two words "touch" and "control", for Nigel Aspinall was one of the supreme technicians of our game. His incisiveness and fluency may have been "machine-like", but, unlike any machine, he sought to extend our notions of the possible. To see Nigel in full flow in his hey-day, usually playing with a battered old mallet - one from his father's second-hand set, he told me - was to see croquet perfection.

[Text and photos reprinted by permission from the July 1999 issue of The Croquet Gazette.]